Historical inaccuracies aside, My Darling Clementine is a Western for the ages

Here’s what My Darling Clementine gets wrong about history: Wyatt Earp and his brothers were never cattle drivers. Before turning to gunslinging, Doc Holliday had been a dentist, not a surgeon, and he died in his bed of tuberculosis years after the events depicted here. James Earp, who’s murdered at the beginning of the movie while still in his teens, actually lived to be 84. The famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral didn’t involve Old Man Clanton—Clementine’s primary, ornery antagonist—as he’d been killed in an ambush a few months earlier (by Mexicans, not the Earps). And the gunfight itself happened in 1881, not 1882.

Here’s what My Darling Clementine gets right about being a magnificent Western: almost everything.

When it comes to a movie this gloriously mythic, there’s no point in getting hung up on accuracy. “Print the legend,” as someone says in a later John Ford picture, and that’s precisely what Ford does here from the moment Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) arrives in Tombstone and proceeds to singlehandedly disarm a drunken Native American who’s terrorized the current marshal into resigning his post. (Casual racism is another wrongheaded aspect of classic Westerns, but that’s the only notable instance in this film.) The Earps want nothing more than to get a shave, a bite to eat, and some rest before moving on to California, but when their cattle get rustled and James Earp is shot in the back, Wyatt pins the marshal’s star on his chest and sets about establishing law and order. His first order of business: negotiating a truce with Doc Holliday (Victor Mature), who’s used to having his own way around town. Fortunately, Doc is distracted both by his current flame, saloon singer Chihuahua (Linda Darnell), and by the unexpected arrival of ex-sweetheart Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs), who also catches Wyatt’s eye.

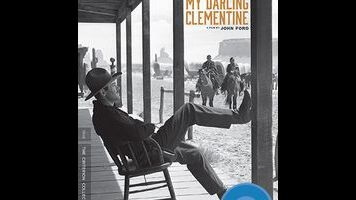

Not for nothing is this film titled My Darling Clementine rather than, say, Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (1957, with Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas) or Tombstone (1993, with Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer). For a movie that’s building toward the most famous gun battle of the Old West, it’s in no particular hurry to get there, content to dawdle with Wyatt Earp on a storefront porch as he leans his chair back on its hind legs, one boot propped against a wooden post—an image so iconic that Criterion chose it for the cover of its new DVD/Blu-ray edition. The feud with the Clantons percolates quietly in the background while Wyatt and Doc slowly develop a mutual respect, and this is the rare Ford Western that’s genuinely interested in its women, even if there’s a clear madonna/whore dichotomy happening with Clementine and Chihuahua. My Darling Clementine is lazy in the best way, allowing both the characters and the town itself to breathe; when violence happens, it’s all the more wrenching, coming across almost like a violation of nature.

Speaking of violations: Ford’s original cut of the film was almost certainly even more laid-back, running over two hours. This didn’t sit well with Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck, who trimmed it down by about 30 minutes and hired Lloyd Bacon (42nd Street, Footlight Parade) to reshoot certain scenes. The original cut is presumed lost, but a preview version running six minutes longer than the release version was discovered in the ’90s, and is included on the Criterion disc, along with a lengthy video essay detailing every difference between the two. Ford evidently wanted to use less music, show more incidental Tombstone business, and avoid crowd-pleasing cuteness. (Zanuck reshot a farewell handshake to add a tender kiss, for example.) Still, this isn’t Greed or The Magnificent Ambersons. Ford’s cut might have been a smidge greater, providing some additional atmosphere, but the shorter version remains fundamentally his vision.

And what a vision it is. My Darling Clementine is chock-full of terrific actors (some of them practically in bit parts—two of Wyatt’s brothers are played by Ward Bond and Tim Holt, and John Ireland scowls up a storm as Billy Clanton), and features both one of Fonda’s finest performances and a rare opportunity for Walter Brennan, as Old Man Clanton, to play a villain rather than his usual mealy-mouthed sidekick. All the same, it’s the stunning images that lodge in the memory. Cinematographer Joe MacDonald, who’d go on to shoot such films as Panic In The Streets, Pickup On South Street, and Bigger Than Life, somehow makes day-for-night footage look spectacularly foreboding rather than cheesy, and Ford unerringly knows when to move in close and when to keep his distance. At one point, a major character has been shot, and Doc has to operate. “Look,” he says, “I haven’t got anything to put you to sleep, so this is gonna hurt like blazes.” Ford cuts on that line to another character involuntarily taking a step backward in horror, then a few shots later, when the surgery begins, cuts to a long shot from across the room, with the actors barely visible behind a foreground shrouded in darkness, and the focus on extras sitting at the bar nursing their beers. Those two cuts are more visceral than anything that happens a bit later at the O.K. Corral. And it’s a hell of a gunfight, too.