History repeats: First as tragedy, then as farce, and finally as a rote biopic in The Young Karl Marx

Last year marked the 150th anniversary of the publication of the first volume of Karl Marx’s Capital: Critique Of Political Economy, which did for social science and political economy what Charles Darwin’s On The Origin Of Species had done for biology. Yet the formidable book took five years to sell 1,000 copies in the original German and another 15 years to be translated into English (despite the fact that it was written in England), and the first volume ended up being the only one that Marx ever completed. Although they still bear his name, the other two were prepared from Marx’s notes by his friend and benefactor, Friedrich Engels.

Theirs was a fruitful and unlikely intellectual partnership: Marx, the irritable, stateless family man, living hand-to-mouth with his aristocratic wife, Jenny Von Westphalen; Engels, the wealthy son of a textile manufacturer, a man of dinner parties and good company, his views on marriage as a corrupt institution shared by his partners, the illiterate, radical Irish sisters Mary and Lizzie Burns.

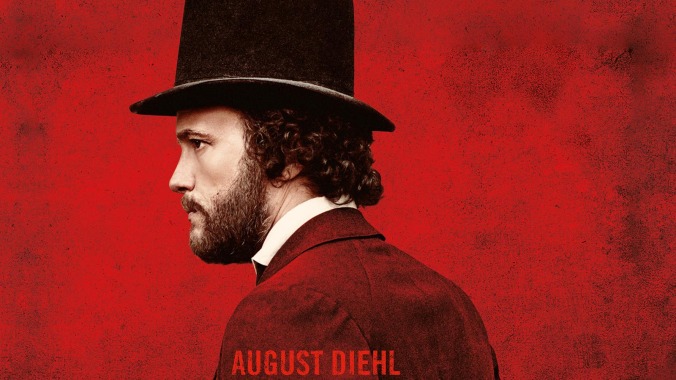

Conventional in everything except its subject matter, Raoul Peck’s biopic The Young Karl Marx dramatizes the lives of the two historical-materialist titans from 1843 to 1848, the year they co-authored The Communist Manifesto. It wasn’t until the summer of 1844 that the men actually met at the Café De La Régence in Paris, then the most famous chess café in Europe—an auspicious foreshadowing. Instead, we are introduced to Marx (August Diehl, probably best known to American audiences as the SS officer with the “King Kong” card on his forehead in Inglourious Basterds) in Cologne, arguing his theories of property even as the Prussian authorities arrive to shut down his newspaper, the Rheinische Zeitung. Engels (Stefan Konarske), still a long ways from growing his fabulous mammoth-shag beard, is in Manchester, where he meets Mary Burns (Hannah Steele) while researching what will become his first book, The Condition Of The Working Class In England. She has just been fired from his father’s mill and at first takes Engels for another slumming bourgeois.

But, to quote the famous opening words of The Communist Manifesto, a specter is haunting Europe. It seems that in the mid-19th century one couldn’t open a door without hitting a political philosopher, and Marx runs into two shortly after he and Jenny (Phantom Thread’s luminous Vicky Krieps) relocate to Paris: Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (Olivier Gourmet), of “Property is theft” fame, and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin (Ivan Franek). Peck, the Haitian filmmaker best known for the Patrice Lumumba biopic Lumumba and the recent James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro, is chiefly interested in the era’s intellectual ecology. His thesis comes through loud and clear: that Marx and Engels brought scientific rationalism to a movement that was being pulled in different directions by resentments, cults of personality, and atmospheres of paranoia not unlike the ones that would be justified through their words a century later.

The script, co-written by Peck and the prolific French screenwriter Pascal Bonitzer, almost implies that Marx was wrong in at least one respect—that in history, sometimes the farce comes first. Proudhon bristles as his protégées refer to him as “the master” without a hint of irony, while the tailor-turned-radical-activist Wilhelm Weitling (Alexander Scheer) can’t stop speechifying even in private. But the texture and energy of the time are treated as an afterthought. It doesn’t help that almost everyone is too old; the fortysomething Diehl is playing Marx in his 20s, while Franek and Gourmet are both playing men in their early-to-mid-30s, despite being very clearly in their mid-50s. From its lifelessly anachronistic English dialogue to its Masterpiece Theatre lighting and production design, The Young Karl Marx tries to filter radical thought through the pace and aesthetics of a middlebrow drama. Its politics wrapped in trappings as familiar as a recycled period costume, the film seems so competently genteel that it comes as a shock when Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone” bursts in over the end credits—an injection of ambitious rock ’n’ roll swagger that comes too late.