When it comes to the films of Japanese writer-director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, the most apt comparisons have long been Fritz Lang and David Lynch, even though neither speaks to how his movies actually look. Like the former, he draws on a fascination with evil (one can imagine Lang’s masterpieces M and The Testament Of Dr. Mabuse remade as Kurosawa movies), and like the latter, he merges the macabre and the everyday in a way that unsettles feelings about both. In his films—which include Cure and Pulse, both classics of modern horror that rank among this publication’s favorites—an eerie and unclassifiable atmosphere of mystery grows around familiar genres: the detective procedural, the domestic drama, the ghost story. These movies find a way into the cosmic and unknowable through pulp clichés (overworked cops, supercriminals, subterranean lairs, etc.) and apparent predictability. Their repetitions become more mysterious with every occurrence, and their characters, drawn irrationally through dreamlike narratives, are just as easily viewer doubles.

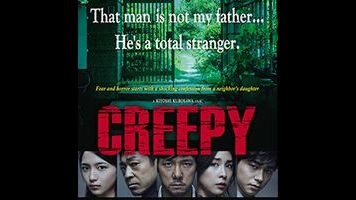

Creepy, Kurosawa’s perturbed and darkly funny adaptation of a novel by Yutaka Maekawa, takes as its starting point a couple of exhausted stock suspense set-ups: the cold case and the suspicious neighbor. Its protagonist is Koichi Takakura (Hidetoshi Nishijima), a former detective who resigned from the police force after failing to defuse a hostage situation that involved an escaped serial killer armed with a fork. Settling into a new home in a Tokyo suburb and a university position teaching criminal psychology, the fortyish and happily married Takakura soon becomes preoccupied with two seemingly unrelated mysteries: the unsolved disappearance of the Honda family, who left behind a now-grown daughter who claims to not remember what happened; and the strange behavior of his new neighbor, Mr. Nishino (Teruyuki Kagawa), a financial analyst with a sickly wife and a teenage daughter of his own.

Bug-eyed and clammy, Nishino belongs in the pantheon of next-door weirdos, swishing from personably awkward to coldly standoffish as though they were steps in a waltz that only he can hear. Kagawa, who starred in Kurosawa’s Tokyo Sonata as a white-collar family man with a very different type of secret, is a marvel to watch; when Nishino and Takakura run into each other on a commuter train, he gives a grimacing courtesy smile that falls somewhere in the uncanny valley. In a deftly concealed bit of dream logic, neither “case” originates with the ex-detective; the mystery of the Hondas is pressed on Takakura by younger colleagues (first a grad student, then a twentysomething acquaintance from the police force), while Takakura’s wife, Yasuko (Yûko Takeuchi), is the first to suspect that their new next-door neighbor isn’t what he seems. In that respect, the mysteries—which grow weirder and weirder until they start to merge—are perversions of established comforts: the logic of detective work, the steadiness of a marriage.

Kurosawa’s spatial, ambient style creates ambiguities out of sharp-edged frames. He is a complete classicist in the importance he puts on staging, and the influence of the tough-guy genre movies of Don Siegel, Richard Fleischer, and Robert Aldrich—often cited by Kurosawa as personal favorites—is plainly obvious in the way he frames Takakura and his former colleagues. But his sense of emphasis is inverted: What other filmmakers do with close-ups or shadows, he does with wide shots, ellipses, and empty space. And the more successfully Creepy rationalizes itself, the more irrational it becomes, until it descends into one of those decrepit subterranean spaces that have stood in for the recesses of the psyche in Kurosawa’s movies. Under the (literal) surface of a drab suburban development, it finds a soundproofed mad scientist’s bunker, complete with a trap door straight out of a silent movie: a vision of absolute evil that somehow becomes more disquieting and suggestive as it becomes more obvious and literal.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.