Housebound devises a novel solution to a common haunted-house-movie problem

As horror films have become more self-aware in the post-Scream age, filmmakers have been forced to come up with plausible reasons why people being menaced in a particular location don’t simply leave. Populating the movie with cretins just won’t do anymore. One possibility, explored by Insidious a few years back, is that they do leave, but the malevolence follows them. (The superb indie It Follows, coming to theaters next year, takes this idea to the extreme.) Housebound, a horror comedy from New Zealand, tries another tack: Its protagonist doesn’t leave because she legally can’t. The movie doesn’t get nearly as much mileage from this concept as it might have, getting bogged down in an increasingly silly plot having nothing to do with house arrest, but the premise does at least justify a hilariously antisocial leading lady.

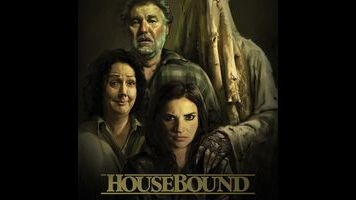

That would be Kylie (Morgana O’Reilly), who’s first seen attempting to rob an ATM with a sledgehammer and explosives. Caught while fleeing the scene, she’s sentenced by a lenient judge to eight months with her mother, Miriam (Rima Te Wiata), at her childhood home, which for Kylie is arguably worse than jail. An ankle monitor ensures that Kylie can’t get more than a few yards away from Miriam’s incessant blather without triggering an alarm. But it also means that when she hears strange noises in the night and sees scary figures in the basement—confirming mum’s long-held conviction that the house is haunted—she can’t flee in terror. Her only solace is discovering that Amos (Glen-Paul Waru), the security officer who monitors her device, fancies himself an amateur paranormal investigator and is very keen to help out.

Not that she necessarily needs anyone’s help. If Housebound is ultimately much more funny than scary, it’s because O’Reilly’s pugnacious performance runs so counter to the genre’s usual treatment of women in peril. When a scary-looking child’s toy appears at Kylie’s bedside in the middle of the night and starts saying creepy things, she doesn’t scream or cower—she picks it up and punches the living shit out of it, then throws it into the fireplace. When a closet door in her room mysteriously swings open of its own accord with the requisite foreboding creak, she immediately removes it from its hinges. It’s likewise fun to watch her spit venom at Miriam and harass the court-ordered shrink (Cameron Rhodes) who shows up for counseling sessions. The indignity of being trapped in a home that she’d escaped as early as she could is merely compounded, for her, by the irritation of also being trapped in a cheesy horror movie.

Trouble is, the horror movie gets too cheesy. Revealing much about what happens wouldn’t be fair, but there’s considerably more to the situation than initially meets the eye, with revelations afoot concerning the house’s history, an exceedingly odd next-door neighbor (Mick Innes), and an unsolved murder. The ludicrous solution to these mysteries would have perfectly suited a Scooby-Doo episode, but first-time writer-director Gerard Johnstone only occasionally treats his third act with the mockery it deserves, and the sheer amount of time he devotes to this nonsense derails the character comedy that had been the film’s forte. Nor does he figure out a way to make the climax hinge on Kylie’s house arrest—by the end of the film, that detail is all but irrelevant. (She deliberately cuts the ankle bracelet to get help, but that’s it.) What began as creative innovation devolves into generic frenetic action, and suddenly it’s the audience that’s ready to leave.