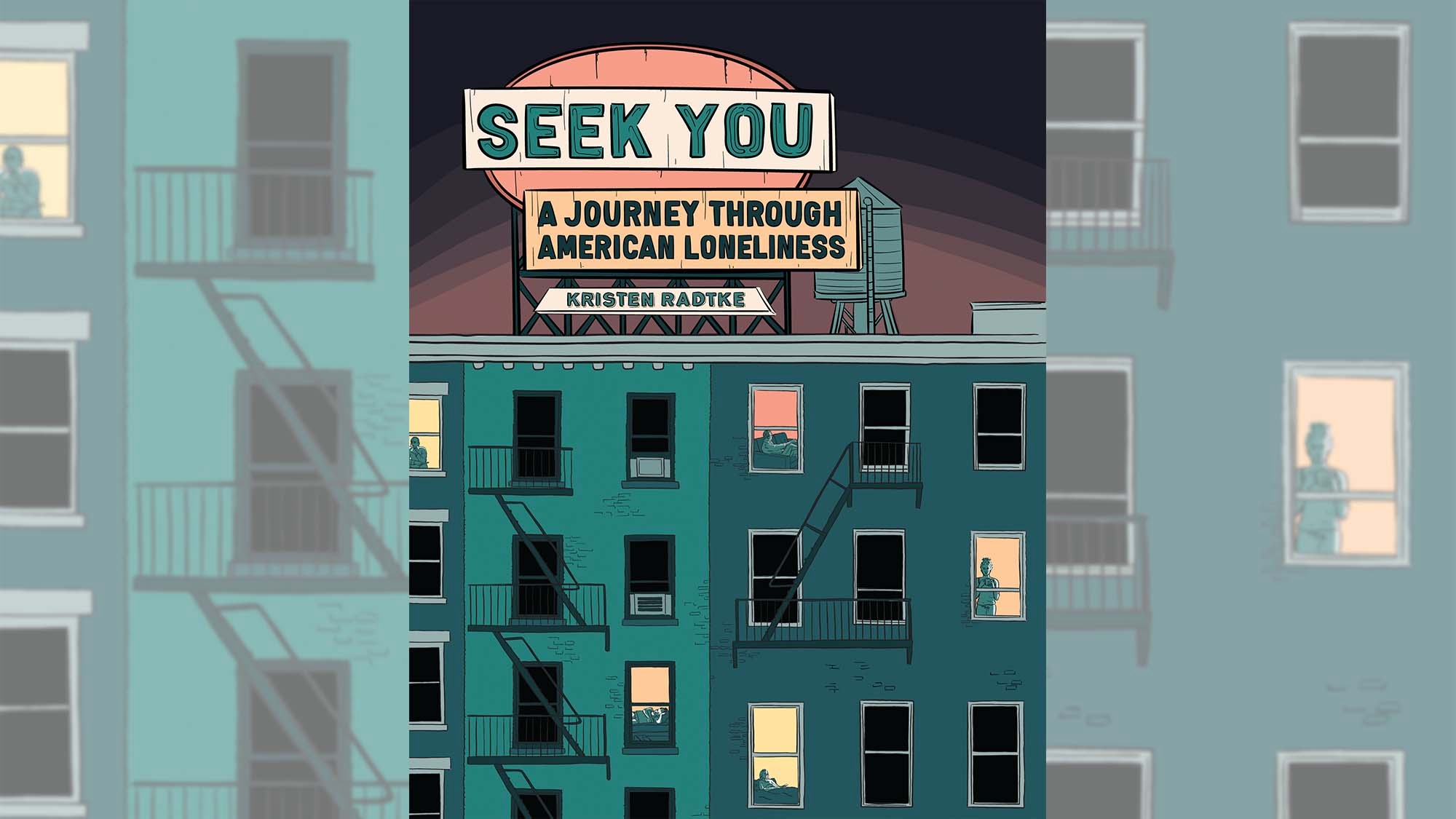

How do we solve a problem like loneliness? In Seek You, Kristen Radtke looks for an answer

In her latest work of graphic nonfiction, illustrator and writer Kristen Radtke considers the causes and effects of a national epidemic

It’s a decidedly This American Life sensibility on display in Kristen Radtke’s Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness. The writer and illustrator’s latest work of graphic nonfiction is curious, compassionate, and, yes, occasionally whimsical. But unlike TAL, which usually divides itself into two or three chapters, Radtke walks several paths in her exploration of “one of the most universal things any person can feel,” considering the quaint (ham radio and the laugh track), the quotidian (public transportation), and the disquieting (mass shooters and the estranging effects of social media).

Radtke began writing Seek You in 2016, long before, she says, the pandemic made loneliness a common topic of conversation. As with so many societal problems, COVID threw unwanted isolation and the systemic failure to address it into stark relief, while also exacerbating it. Yet years before the coronavirus took hold, major news outlets were already calling loneliness an epidemic. Perhaps for that reason, much of what Radtke relays here is familiar. She cites the truism that being alone doesn’t necessarily mean you’re lonely, and, vice versa, that surrounding yourself with others doesn’t inoculate you from the feeling. She spends significant time summarizing results of studies that demonstrate just how damaging unwanted solitude is, providing scientific evidence for truths that many know intuitively. One obvious conclusion reinforced through her data: Loneliness is painful in the moment, but it can also lead to defensiveness, with lonely, isolated people more likely to perceive the world as threatening, decreasing their likelihood of trying to connect with others in the future, thus creating a vicious cycle.

Similar to a writer like Maggie Nelson, Radtke collages different genres—autobiography and social science and criticism—rather than drawing out a single story or argument. The effect is one in which fewer insights are revealed than they are assembled. Her chosen subjects can feel on the nose, as in the section where she describes untraditional methods to alleviate loneliness, like hiring platonic cuddlers or nursing homes giving seniors robotic companions. Radtke skips over more enriching (and free) solutions in favor of these quirky band-aids. Why investigate one but not the other?

Running throughout Seek You is the idea that art can both connect people and distance them from one another, exemplified by Radtke’s dissection of the depiction of solitude in film and television. Men have long been portrayed as cowboys, haunted loners who can decide to be unlonely at any moment, either by riding into town or merely returning to their families after making yet another stop on their tour of extramarital affairs; here her color illustrations go from cool teal to sun-baked orange and red, underlining such characters’ allure. Solitary women, on the other hand, particularly those in romantic comedies, are virtuous lonelyhearts who must wait for men to solve their predicaments for them. This double standard is less revelatory on its own than when one remembers that earlier in the book Radtke tells of the hours of television she watched as a solitary teenager. What at first seems edifying (“The laugh track of each show was a lesson in what I was supposed to feel and know”) is later understood as presenting a rigid mold for how to be.