How Law & Order’s Paul Robinette embraced his revolutionary Blackness

“Ben Stone once said I’d have to decide if I was a lawyer who was Black or a Black man who was a lawyer. All those years I thought I was the former. All those years I was wrong.”

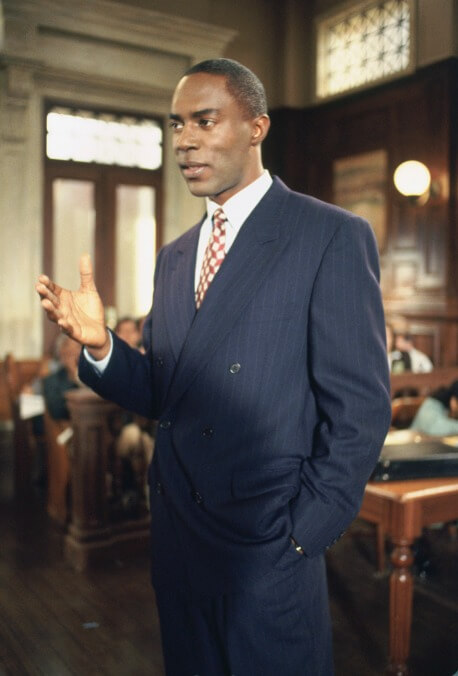

Paul Robinette’s (Richard Brooks) parting words to Jack McCoy (Sam Waterston) in “Custody,” the 14th episode of Law & Order season six, are more than just a callback to a heated exchange from an earlier episode. They’re a declaration of purpose, a Black man rejecting a system he once faithfully served. “Custody” is revelatory, and throughout, Robinette is defiantly, unapologetically Black. He wasn’t always.

When Law & Order debuted on NBC in September 1990, Robinette was the young ADA under Executive ADA Ben Stone (Michael Moriarty). I admired Robinette’s flat-top fade. I also envied his bad-ass baritone, especially when he instructed the detectives to “pick ’em up.” The network had several popular series with predominantly Black casts: The Cosby Show, whose star would eventually appear in a real-life courtroom, A Different World, and The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air, the latter of which premiered the same week as Law & Order. But Robinette was the lone Black representative in the criminal justice system. This isn’t to say that Law & Order was anything like Friends or Seinfeld. Black people existed in this New York. We were put-upon secretaries, seen-it-all cabbies, and, yes, junkies, dealers, sex workers, and scary guys on the subway. We provided the show’s urban reality.

Compared to future cast changes, Brooks left the series without ceremony. In 1993, NBC noticed women existed and asked producer Dick Wolf to include a couple in the season four cast. Captain Donald Cragen (Dann Florek, who would later star on the spin-off Law & Order: Special Victims Unit) made way for Lieutenant Anita Van Buren (S. Epatha Merkerson), and Claire Kincaid (Jill Hennessy) replaced Robinette as the A.D.A. Van Buren, a Black woman, overseeing the detectives in the 27th Precinct was a refreshing change, but a Black prosecutor would never again work in the show’s D.A. office. Connie Rubirosa (Alana de la Garza), the daughter of a Spanish immigrant father and Mexican mother, was second-chair A.D.A. for the final four seasons.

No reason is given for Robinette’s departure. In a deleted scene, Van Buren asks to see him and Stone tells her to take a “cab uptown… Park Avenue. Woodward, Martin, and Schwartz.” I’m glad this never aired, as the scene would’ve left the impression that Robinette pursued a more lucrative career in private practice—understandable but not necessarily noble or the result of any great inner conflict.

Law & Order rarely showed us the personal lives of its characters, but there were often clever, subtle hints of who they were off the job: McCoy’s motorcycle helmet and Kincaid’s fly as fuck leather jacket, for instance. Detective Lennie Briscoe (Jerry Orbach) had a solid standup set about his ex-wives. Robinette was more elusive. He was reserved, stoic, prosecuting offenders without an obvious agenda. He never mentioned going home to a wife or girlfriend (this was 1990, so those were the network-approved options). We never even saw him leaving to meet up with friends for drinks.

“Custody” tells us more about Robinette in one episode than we’d learned over three seasons, and it actually makes his previous appearances richer upon rewatch. He returns as a defense attorney, a courtroom adversary to McCoy and his own replacement, Kincaid. But he’s not some slick hired gun representing whoever can afford his fee. He’s defending Jenny Mays, a Black former crack addict who tried to kidnap her child from his white adoptive parents. She’s not a clichéd “perfect victim,” and a man died as a result of her actions. It’s what Stone would’ve considered clear-cut felony murder, but his former ADA now passionately declares it “justice.”

There’s an interesting parallel to the first season’s “Subterranean Homeboy Blues” (yeah, I know). Laura Di Biasi (Cynthia Nixon) is charged with shooting two Black men on a subway. She claims it was self-defense, but compelling evidence exists that she’d targeted random Black guys in revenge after an unrelated assault. There’s a cringe-worthy moment when she appeals to Robinette, who she accuses of “hating” her. She insists, “I wouldn’t shoot you.” She seeks absolution from a Black man for her crime against Black men. She “reassures” Robinette that she considers him “different” from the men who apparently terrified her so much she had no choice but to open fire (even though one of the men was seated). The “compliment” she offers Robinette is one “presentable” Black men often receive from the back of a white hand, but “Custody” shows that Paul doesn’t want to spend his life as “the good one.” He wants to use his talents to help his entire community, not just himself.

This is a major change. When Stone asked Robinette if he was a “lawyer who was Black or a Black man who was a lawyer,” it was a loaded question, as Stone likely considered only one option honorable. Robinette admits that he’d defined himself as the former, as someone who saw his race as separate from his identity. He was the great white moderate hope. He even opposed affirmative action. In “Out Of The Half-Light,” an episode ripped from then-recent headlines surrounding the Tawana Brawley case, Robinette naively informs Black congressman Ronald Eaton (an obvious Al Sharpton stand-in) that “we’re past the separate drinking-fountain stage. We’re past legal discrimination. We’re at the hearts and minds stage.” Almost 30 years later, current events reveal how absurd that sentiment is.

Robinette rejected Eaton’s belief that the “ends justify the means” when seeking racial equality. But as opposing counsel in “Custody,” he argues that transracial adoption is a form of racial genocide; because the entire welfare system is racist, his client was justified in using whatever means were necessary to take back her child.

Ironically, Robinette is now more like McCoy than the fiercely principled Stone. He’s willing to bend the rules to force a potentially hostile judge to recuse himself. When McCoy accuses him of “bullying” the judge, Robinette points out how much power the D.A.’s office wields: “I’m a bully? I don’t have 500 attorneys in my office or a $200 million war chest, the power to investigate and arrest any citizen and a well-armed police force to back it up. That’s you, Jack. You’re the biggest badass on the block.”

Wolf considered Kincaid “the most politically left character” in the show’s history at that point, but that assistant A.D.A.’s (white) feminism goes only so far. She’s not moved to identify with Mays despite their common gender. She suggests that Robinette is using bigotry, which she views as simply individual bad actors, as an “excuse” for “any Black criminal” to avoid accountability. Robinette counters that true justice would consider the institutional racism that Black defendants endure a “mitigating factor.”

McCoy isn’t pleased when he’s forced to offer Robinette’s client a plea deal after the case ends in a mistrial. He tells Robinette that he’s a “long way from the District Attorney’s office,” and it’s obvious that the door to this office has slammed shut behind Paul. Earlier, District Attorney Adam Schiff (Steven Hill) had compared Robinette with no shortage of contempt to a member of the Nation of Islam, effectively equating his overt “pro-blackness” with Louis Farrakhan’s anti-semitism.

Robinette would return to Law & Order two more times: In season 17’s “Fear America,” he defends a Muslim man, Ben Faoud, who he argues the prosecution has unjustly painted as “a terrorist and a murderer” or, bluntly, “one of them.” However, his client in season 16’s “Birthright” is a white woman, Gloria Rhodes, who has sterilized dozens of young Black and Hispanic women without their consent. One of her victims—Traci Sands, a murder suspect with a history of child neglect—dies as a result.

McCoy and Robinette’s relationship has grown more cordial over the past decade, and after the case has ended, the two men share drinks. McCoy asks Paul how he could defend someone like Gloria Rhodes, and his response is fascinating. “I could give you reasons—the good she’s done with the clinic, innocent until proven guilty — but tell me your job wouldn’t be easier if people like Traci were never born, that the world wouldn’t be a better place.” McCoy “won’t say that,” but Robinette counters that he already had when he conceded that Rhodes wasn’t Auschwitz “Angel Of Death” doctor “Josef Mengele.” He continues: “Nobody wants to admit they think [Rhodes] did the right thing, but if they look for it—you look for it—deep down, it’s there. That deserves a defense.”

How does this square with the Robinette who’d defended Jenny Mays? He sounds shockingly similar to the judge in “Custody” who supported forced sterilizations, but I don’t think he’s suddenly more conservative than McCoy. His closing statement from “Custody” still stands: He’s a Black man who is also a lawyer, and that will forever alter how he views the system and the methods necessary to achieve true justice in and out of the courtroom.