There’s an odd contrast between the organic and inorganic at the heart of Pola Oloixarac’s writing. The Argentinean author relishes in teasing out curlicues of digital code that execute far-reaching programs, or producing dizzying passages in which the macro scale of global economies and political systems are scrutinized as though under a microscope. The results are often lovely and entrancing, even when she turns them to darkly satirical purposes.

And then there are her descriptions of the human body, especially when engaged in sexual acts, where the messiness of all that wobbly flesh and rushing fluids does something strange to her words. Namely, they become ridiculous, and even if the shift is intentional, it results in some truly cringe-inducing descriptions. Here’s one of her main characters encountering a woman’s vagina for the first time:

Welcome to the strange and frequently wonderful world of Pola Oloixarac.

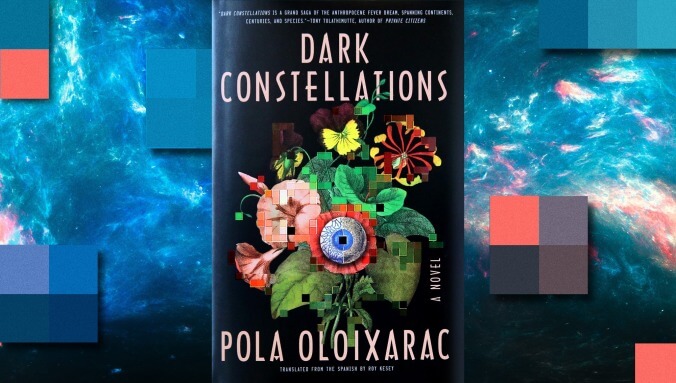

For being a modestly sized novel (barely 200 pages), Dark Constellations is practically galactic in the stretch of its narrative ambitions. Beginning in the Canary Islands in 1882, it recounts in history-book-like prose the journey of a British botanist and his colleagues as they encounter a native population with whom they share a viral-like hallucinatory sexual escapade that lasts weeks. From there, it leaps forward a century to Buenos Aires, where disaffected young hacker Cassio, connected through strange genetic bonds to the mysterious expedition a hundred years prior, is learning to create viruses of a far different nature at the same time his own awkward and clumsy body is pulling him back to the banalities of everyday reality. He has visions of world-altering creations, of developing inorganic beings that will transform not just the world around people, but people themselves—a messiah-like complex, only it’s not humanity he’s interested in saving, but what it has the potential to become.

The third part of the novel jumps to the near future, where Cassio, now working on a massive government-funded project involving human DNA and coding, meets Piera, a woman with a mind and imagination to match his own. With an inventive eye for the implications of contemporary digital processing power that would make Neal Stephenson proud (while also possessing shades of Roberto Bolaño), Oloixarac sends her characters into a confrontation with the legal and ethical ramifications of humanity’s rapidly dwindling ability to keep a tight leash on whatever is currently being hatched in hacker collectives and corporate think tanks alike. Or, as a character succinctly puts it, “There’s a race going on between technology and politics, and it’s obvious which side is best equipped to win.”

If this all sounds very vague, that’s because Oloixarac has intentionally crafted a labyrinthine project for her characters, one that blends the synthetic and organic, the human and inhuman, and would require more space to explain than a simple summary permits. But it’s also because the author wants to purposefully blur the lines between her stories, to apply the same hallucinogenic effect that her 1880s botanist spends his time obsessing over to her prose on coding and data harvesting, resulting in a book that suggests more than it reveals about the connections between biological exploration, digital exploration, and the dangerous promise inherent in combining them.

In some ways, this is a linear continuation of the interests that marked her debut novel, Savage Theories, with its biting look at academia and critical theory that eventually spun into a tale where people struggled to locate themselves in a landscape of fractured online existence and revolutionary video games. But where that book’s political satire was searching, Dark Constellations’ is damning. The sharply observed mockery of contemporary Silicon Valley-style tech culture (here relocated to a South American equivalent in the Andean foothills) is funny and incisive, as Piera acidly notes that the arrival of a girl in a tech startup’s ranks is seen as a “preamble to decline… it signified that the normal period was starting, full of unmarried females and middle management, i.e. mediocrity.” (This is preceded by the arch reflection that “Heterosexual camaraderie is an extremely thin parabola.”)

But those small observations are balanced with enormous, paradigm-defining assessments of capitalism, liberalism, technology, medical advancement; Oloixarac lays out bold but lovingly textured descriptions and diagnoses of all these things, and they nearly always sound provocative and artful. A typical example is the way she unites the spirit of ’60s hippie anarchism with that of ’80s conservative financial radicalism: “The two movements—hippie/randomizing and financial/conservative—share a disdain for industrial corporations and factories, the former because industry embodies the value of their parents, the latter because industry entails a theory of value that competes with the absolute liberalism that the poetic flight of capital (viz. ever more distant from the gold standard) seeks for itself. And both movements endeavor to rise beyond the guiding industrial paradigm of progress. Their hearts bear the mark of technology.”

This is her version of philosophic writing, just one aspect of the novel, and it always crashes back into the engaging forward momentum of her protagonists as they barrel ahead in life, looking to give their existence meaning. Unfortunately, it also runs smack into moments where she refers to penises as “meatworms.” The silly repellency of her sexual descriptions almost acts as a comic foil to the elegant profundity of her conceptual themes, but they still feel a bit like record scratches that pull the mood up short. Luckily, she’s crafted a weird and absorbing cyberpunk tale that can sustain such odd interludes. It ends a bit too abruptly, like Oloixarac is trying to pull the plug just as it’s getting very interesting (and twice as complicated, admittedly), but the “what if” tone of the conclusion is thought-provoking in its own right. Dark Constellations should find her a new audience of readers hungry for strange and all-too-plausible tales of our modern, algorithm-driven lives, but it reaffirms a stereotype about brilliant philosophical writers: They often stumble over the dirty stuff.