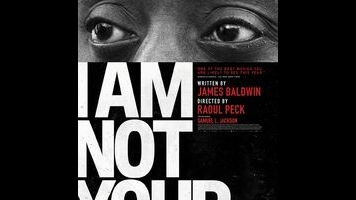

Raoul Peck’s docu-essay I Am Not Your Negro is narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, speaking in a voice so low and affected that he hardly sounds like himself. He doesn’t quite sound like James Baldwin either—or at least not like the mellifluous, twangy Baldwin seen in the old clips from talk shows and public affairs programs scattered throughout Peck’s film. Jackson sounds more like the author late at night, exhausted, half-whispering bitter truths into a tape recorder. I Am Not Your Negro could be considered one of the final statements from a great American writer, and it’s a sadly resigned one, summarizing centuries of overt and subtle racism and expressing a feeling of hopelessness. To say that this movie is as relevant now as it was when Baldwin was alive is no great analytical leap. The trends of these times would not have surprised the man himself. As repeated throughout Peck’s film, Baldwin never had much faith that black people could ever live in a United States where they’d wake up in the morning without at least some worry that they’d be shot dead by nightfall.

I Am Not Your Negro is based on a nonfiction assignment that Baldwin turned down in the late ’70s—after writing 30 pages framing what the project might’ve become, and explaining why he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Tentatively titled Remember This House, the book was meant to be a look back at the lives and deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King filtered through Baldwin’s own personal experiences with all three. But Peck’s film isn’t strictly an adaptation of an unfinished work, or even a backdoor bio-doc about three key figures from the ’50s and ’60s civil rights movement. By weaving in old speeches, pieces from other books, and even some visual juxtapositions that maybe only he fully understands, the director makes a persuasive, intuitive case for Baldwin as a poet and a prophet.

Peck ventures far beyond Baldwin’s thoughts on Evers, X, and King. The overall structure of the film is broken up by the author’s specific recollections of his friends’ respective assassinations and funerals, but on the whole I Am Not Your Negro is more interested in how that trio and the nation they were fighting to improve inspired one man to get off the sidelines and come back to the States after years of living and writing in Paris. Jackson reads moving recollections of how ashamed Baldwin felt by images in the newspaper of black students being shouted at as they integrated white schools. The writer would also say in his correspondence that he came back because he’d begun to pine for the company and culture of his own people. (“I missed the way when a dark face opens, light seems to go everywhere,” Baldwin wrote.) With that mix of moral duty and homesickness as a starting point, Peck adds large swaths of his subject’s autobiography, mostly directed toward his deeply conflicted experiences as one of white America’s favorite black intellectuals.

The predominant use of Baldwin’s words (aside from a few scattered lines from others in old film and TV clips) is I Am Not Your Negro’s main selling point. Few Americans in literary history have strung phrases together as beautifully or cogently as the man who wrote Go Tell It On The Mountain and The Fire Next Time. He’s a pleasure to listen to, either via Jackson or in archival footage. Baldwin was naturally and productively provocative too, whether he was explaining that Malcolm X’s fiery rhetoric appealed to so many because he “corroborates their reality,” or he was offering scathing, knowing critiques of the white-centric myth-making of John Wayne Westerns and Sidney Poitier social dramas.

The film also serves as a compendium of the kind of images that rarely appear in the more optimistic surveys of the civil rights movement. There are clips here not just of marchers being pushed around by cops, but also of white-power rallies where people held shockingly racist signs and made statements insisting that integration was a greater sin than murder. Peck doesn’t just illustrate Baldwin’s insights into race relations with footage from the ’60s; he works in video from Ferguson, Missouri, and photos of Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin. I Am Not Your Negro doesn’t present itself as ancient history. When Baldwin gets harangued by a Yale professor about individual identity on The Dick Cavett Show, it’s hard not to hear echoes of “All Lives Matter.”

Some of the visuals Peck uses to accompany the text are obvious, while others are more allusive and thus challenging in a different way than the words themselves. But while the subject matter is difficult, the documentary itself is easy to watch and exciting to grapple with. Its biggest strengths are Jackson’s voice and Baldwin’s commentary, which combine to create a distinctively world-weary tone. With a different inflection, the observations here about the white power structure’s ongoing inability to imagine African-Americans as full citizens—even though they’ve been in this country longer than the Kennedys or Trumps—might play as a rousing call to arms. Yet here, when Baldwin sighs, “This country has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you,” the words hang in the air like a gloomy cloud, which will not dissipate until everyone sharing this space recognizes that they can’t see through it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.