One of the most macabre tales in the annals of jazz is the death of the hard-bop trumpeter Lee Morgan in 1972. Morgan, one of the virtuosos of the stylistic explosion that followed postwar bebop, was shot in the chest during a late-night gig at the already notorious Lower East Side club Slugs’ Saloon by his common-law wife and manager, Helen More, and bled to death while awaiting an ambulance that was trapped for almost an hour in a snowstorm. Adding an extra mythic dimension to this gruesome scene was the fact that Morgan had survived a terrifying car crash on his way to Slugs’, reminiscent of the death of his mentor, Clifford Brown, who was killed on the way to a gig at the age of 25, when the driver of the car he was in lost control of the vehicle in a rainstorm. The parallel was not lost on Morgan, who reminisced about Brown before his first set of the night. He was 33 himself, a former teen prodigy who had joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, lost a burgeoning solo career to heroin, and then made a big comeback after meeting More. She was older and had a son Morgan’s age. Theirs was a strange relationship.

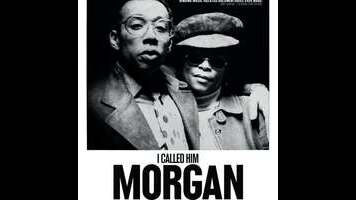

Part character study in codependence, part true-crime doc, I Called Him Morgan examines both of their lives through talking-head interviews with bandmates (including Wayne Shorter, Bennie Maupin, and Billy Harper) and associates, archival photos, and a cassette-tape interview with More conducted in 1996 by Larry Reni Thomas, a jazz historian who befriended her while teaching an adult education class. For Swedish documentarian Kasper Collin (My Name Is Albert Ayler), the true point of interest in the story is More, whose personality emerges in fragments. A widow and mother of two before the age of 20, she escaped North Carolina to New York City, where she made her home a popular hangout for jazz musicians and bohemians. Because Morgan never bothered to divorce his first wife, they were never legally married, but More still informally took his name, referring to herself in the later years of their relationship as “Helen Morgan.” The argument that led her to return to Slugs’ with a revolver was over his relationship with another woman (also interviewed here), though I Called Him Morgan makes it clear that years of drug abuse had left the jazzman impotent. It was, in other words, strictly emotional.

Boasting the Oscar-nominated Bradford Young (Arrival, Pariah) as one of its directors of photography, I Called Him Morgan is never less than attractive and watchable, its gaps filled in with moody footage of wintertime New York shot on 16mm through smeared car windshields and windows. And it has the advantage of relying heavily on stories told by old jazz musicians, who, unlike rock stars, always seem to make good interviewees. (Perhaps it has something to do with the social aspect of gigging and session recording, and the fact that even the titans of jazz first came into their own as sidemen.) But it also never rises above this kind of due competence. There are relatively few photos of the camera-shy More, and while this aura of mystery helps make her side of the story all the more fascinating, it’s something that Collin never settles. When it’s all done, More and Morgan remain ciphers, and not the type whose intangibility is evocative of something greater. All we have are the known facts, and that is all that I Called Him Morgan provides in the end.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.