I Can Only Imagine devoting an entire movie to one bad song

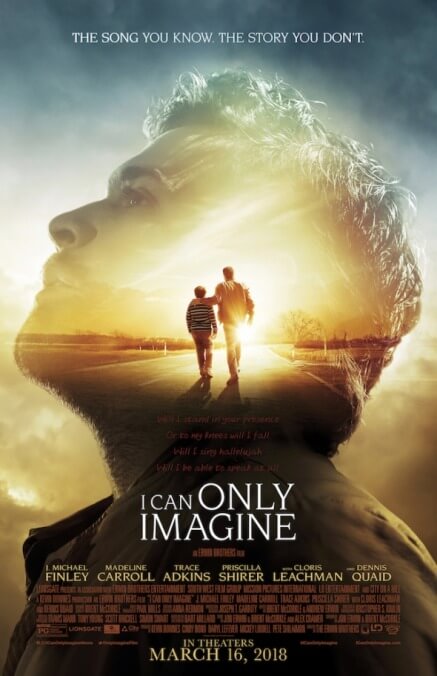

Contemporary faith-based films are usually content to sequester themselves with an audience of true believers, never making much of an attempt to integrate into mainstream movie genres. I Can Only Imagine is not exactly an exception, but it does attempt to engage with less churchy music biographies in one way. In keeping (loosely) with projects like Love & Mercy and I’m Not There that eschew the traditional cradle-to-grave biographical arc, I Can Only Imagine is not the full story of Christian musical act MercyMe. Instead, the non-frontman members of the band barely register as characters, and the movie is essentially an origin story for the song that shares its title, composed by singer Bart Millard (J. Michael Finley).

This is an interesting idea, executed with a reductive, tin-eared understanding of what constitutes art to go along with a faith-based movie’s reductive, tin-eared understanding of what constitutes entertainment. I Can Only Imagine makes cursory attempts to contextualize the song’s success. But the little factoids about what the opening crawl refers to (and weirdly punctuates) as a “multi-platinum, best selling” song aren’t really there for a secular audience unfamiliar with the band; they’re on screen so that audiences can nod in approval about the movie’s preordained redemption story. This may be why a closing crawl makes note of MercyMe’s multiple “#1 hit songs” without specifying that they’re talking about Billboard’s Christian Songs chart, not the Hot 100. Is there even another kind of music, anyway?

For a few minutes of I Can Only Imagine, there is. Bart Millard is introduced as a kid (Brody Rose) who attempts to block out the abuse of his father (Dennis Quaid) by listening to cassettes on his chunky 1985 Walkman. There’s a shiver of bittersweet nostalgia to the scene where Bart bikes madly over to the local music shop before it closes, so he can spend his lawn-mowing money on some new tapes. The record store guy recommends U2, which Bart plays for his mom (Tanya Clarke) on the drive to his hastily procured spot at a Christian camp, where he meets Shannon (Taegen Burns; later played by Madeline Carroll).

Bart’s life changes after camp: His mother moves out, leaving him with his angry, football-obsessed dad, whom Quaid plays with maximum sputtering and eye-bulging, while Shannon’s gift of an Amy Grant tape quietly turns him toward Christian music. Those insufficient semi-Christians in U2 never darken his Walkman again. Bart’s transition to faith music seems like an important one, so naturally the movie glosses it over as if it’s simply what happens when any thinking kid hears Amy Grant. (Actually, the movie isn’t ambitious enough to even really stage an aha moment with the Grant tape; it just gives Bart some awkward dialogue about what a big fan he is later on.)

Soon Bart has matured into a full-on adult, with the unfortunate detail that Finley—who aims for lovable goober but lands closer to garden-variety dumbass—is still supposed to be playing a teenager for a large chunk of screen time. The movie tries to amusingly lampshade this incongruity (“Dude, seriously, that beard makes you look 35”), but a glimmer of self-awareness about some ill-considered casting isn’t enough to wash away the creepiness of a dude who does look 35 romancing Carroll, who is 22 but convincingly playing younger. Maybe the washed-out cinematography is supposed to help with that. Instead, it succeeds primarily in making an already-white movie look whiter still. Even the sky looks Caucasian.

The staging and pacing of Bart’s growth from wannabe footballer to school musical star to passionate musician has that peculiar faith-movie lack of rhythm, as if directors Andrew and Jon Erwin have primarily experienced other movies out of the corner of their eye, or in bits and pieces at the laundromat. This is especially jarring in the scene where Bart meets the other three future members of MercyMe. A band is discussing their lack of a singer on stage at a practice space or venue (the movie doesn’t make it clear); Bart pipes up from the floor, volunteering himself to sing; one of the band members asks who he is; end of scene. The Erwins try to play the final question to Bart as a slightly comic beat, seeming to forget that they really haven’t established who the band is, what the space is, what they’re doing there, what Bart is doing there, and, if he’s supposed to be there, why the band doesn’t know who he is.

Anyway, Bart joins the band and his dad gets cancer. That might sound like a particularly cavalier spoiler, but the movie itself is pretty cavalier with how depicts (or doesn’t) the passage of time and the murky success level of the band as an independent act, perhaps because it’s really only interested in how Bart comes to achieve that sweet adult-contemporary crossover success. When band members talk about their independently released albums, there’s no sense that anyone spent any time actually writing and recording songs (or if they have one album, or 10). They refer to them with the same passion with which one might note that a band had some flyers printed up.

The main event, the heaven-imagining song that the movie treats as some kind of cross between “Where The Streets Have No Name” and the “Hallelujah” chorus, is eventually written in the aftermath of a changed relationship between Bart and his father. Its lyrics are culled from Bart’s journals, which rarely contain more than two sentences per page and often feature the word “imagine” dementedly scrawled at odd angles. This movie is tailor-made for people who will not look at the word “imagine” and think of another song, just as it’s designed for an audience that won’t notice anything strange or contradictory about abusive dads curing themselves via church broadcasts on the radio, or uplifting bands singing passionately about the sweet release of death, or how Bart doesn’t feel successful until he’s on his way to making a shit-ton of money. There’s something interesting to be mined here, at the intersection of faith, forgiveness, and pop music. I Can Only Imagine does its best to ignore it.