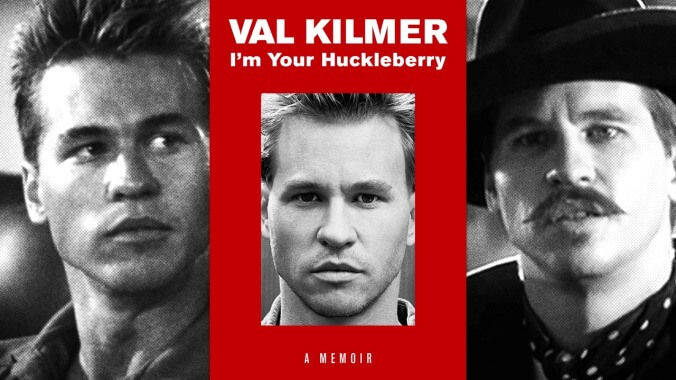

Memoirs were made for confessions, and Val Kilmer’s I’m Your Huckleberry opens with a fairly innocuous one: The actor, artist, and newly minted author admits he readily develops crushes on everything and everyone. He claims to have been called on it by friends and exes, including his former wife and fellow thespian, Joanne Whalley. Kilmer even has a crush on you, the reader, for taking the time to read his collection of anecdotes, poems, and reflections on a nearly 40-year career.

Kilmer’s admission is quickly revealed to be a part of his spiritual beliefs; as a devout Christian Scientist, Kilmer says he’s spent his life trying to let Love, in all its forms, guide him. It’s also the first indication that I’m Your Huckleberry is as much a one-man show as Citizen Twain, Kilmer’s Mark Twain-centered stage show. The erstwhile Batman does open up (to different degrees) in his memoir about breakups, movie sets, and tests to his faith, but always with a mind to entertain. But I’m Your Huckleberry is more sprawling monologue than a retrospective, full of asides and free association, often sanguine and occasionally resigned.

After revealing his latest crush, Kilmer shares a gnarly encounter from his convalescence at the home of none other than Cher, his former flame and lifelong friend, in the first chapter. As he recalls his own blood-soaked grin and laughter spurred by Cher’s fawning over an EMT, Kilmer shows great vulnerability and a knack for storytelling. But over the course of I’m Your Huckleberry’s 300-plus pages, that balance becomes heavily skewed toward the latter; as he makes grand pronouncements about the nature of art and humankind, Kilmer remains hesitant to reckon with his personal carnage.

We do have to cut the Top Gun and Tombstone star some slack for his rose-tinted view. As a survivor of throat cancer (not to mention four decades in an industry notorious for chewing up and spitting out fresh talent), he genuinely seems grateful for the opportunity to look back on his life, loves, and career. But he doesn’t broach those subjects with consistent candor; he first mentions his father’s infidelity and his mother’s alienation almost casually, sandwiching that information between effusive descriptions of his childhood home and haunts in the San Fernando Valley. Kilmer’s memoir returns time and again to his parents, and by the end, he does seem to have reached some kind of revelation about their withholding natures.

Kilmer’s many other relationships receive a less thorough examination. The actor, whose versatility allowed him to play a steel-willed fighter pilot, a rock legend, a washed-up porn star, and, in his own terminology, a dissolute American aristocrat, was just as varied in his friends and lovers as his roles. Kilmer relishes in recounting his first encounters with Mare Winningham, Cindy Crawford, Daryl Hannah, and Angelina Jolie, but backs away before the ends of the relationships, proving himself better at setting the stage than achieving closure in any of these anecdotes. He despairs of his behavior without telling us what it was—Kilmer ends the chapter on his relationship with Jaycee Gossett by acknowledging he’s “a fool.” He goes on: “Oh, you want more detail? ’Cause I’m a big fool. A big stupid fool.” Another confession, but one that, due to the sudden lack of information, feels part and parcel with his other romantic foibles instead of being its own distinct revelation.

Again, some of that glossing over can likely be chalked up to nostalgia and Kilmer’s renewed lease on life. But his reticence also extends to reminiscing about some of his most famous roles—and debacles. There’s not much dishing in I’m Your Huckleberry, the chapters of which are organized by roles: Jim Morrison, Real Genius’ Chris Knight, Top Gun’s Tom “Ice Man” Kazansky, Tombstone’s Doc Holliday, and The Island Of Dr. Moreau’s Dr. Montgomery, among others. His account of his relationship with Marlon Brando, his idol and Dr. Moreau co-star, doesn’t address reports of on-set tensions between the two, so you can forget about getting hot gossip about the wild one. It might just be professionalism, but Kilmer was never shy about communicating his feelings to filmmakers like Oliver Stone, Tony Scott, Joel Schumacher, John Frankenheimer, or Richard Stanley. In interviews dating as far back as 1997, Kilmer has owned up to being demanding. Here, he couches his former imperiousness in enthusiasm and a professed love for the medium, but only issues a mea culpa to a select few.

Occasionally, Kilmer does show the same puckishness and bravado that made him stand out at “THE Juilliard School” (emphasis Kilmer’s), weaving in some truly impressive humble brags about his commitment to realistic portrayals of a gunslinger, fighter pilot, and the Lizard King himself. As he reminisces about working with Kevin Jarre on Tombstone, Kilmer’s downright charming in his grudging acceptance that “sometimes the writer hears his creation with greater acuity than the actor. Sometimes.” Much of the chapter about the making of The Doors is dedicated to how Kilmer reduced veteran producer Paul Rothchild to tears with his uncanny renditions of Jim Morrison’s songs, and Kilmer’s awe at his own prowess is far more endearing than it has any right to be.

Kilmer learned of second chances from his religion and profession: “So yes, I’ve seen redemption in my life. The only thing holier than a crucifixion is a resurrection.” I’m Your Huckleberry is most engrossing, even illuminating, when the author actively tries to reconcile his vision and ego with his faith and regrets. If he loses sight of the past a bit while setting up the next chapter of his life, it’s hard to begrudge him the glance forward, even if it does render I’m Your Huckleberry a series of ellipses instead of a statement on a life 60 years in the making.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.