Boy soldiers chop heads under the command of a Fagin-like child molester, living like zombies and snorting cocaine cut with gunpowder, convulsing in the fetid standing water of a red clay trench—each horror rendered as a slow-mo shot where the sound gradually drops out or as a long Steadicam take, intense and disturbing only in italics or quotation marks. Here, director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s studied, somber professionalism appears to have gotten the better of him, because though Beasts Of No Nation is a long-in-the-works passion project that Fukunaga wrote, produced, and shot himself, it still plays an awful lot like an impersonal calling-card technical exercise—all unreturned stares and glaciers of Tangerine Dream-esque synth, hedged on viewer identification with a cast of non-professional child actors who don’t do much but give blank looks that can be projected with the trauma of civil war. And yet it doesn’t brush off easily.

Perhaps it has something to do with the Commandant (Idris Elba), the leader of a makeshift battalion fighting on behalf of Supreme Commander Dada Goodblood’s NDF in an unnamed West African country. Controlling his “men” through a combination of magic ritual, drugs, and grooming behavior, the Commandant is both predator and pathetic figure, a classic deluded ego—the loser king of traumatized children, given authority by his rich baritone voice and the tacit approval of monsters shrewder than himself. The Commandant may not be the central character of Beasts Of No Nation, but he’s the only one that matters, because he represents a vision of something at once horrifying and sickly compelling in a movie that’s short on unifying visions.

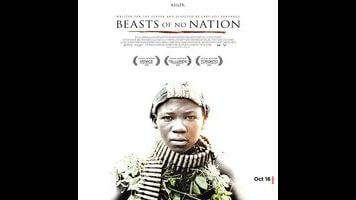

Beasts’ protagonist is Agu (newcomer Abraham Attah), a young boy who loses most of his family only to fall under the sway of the Commandant, who initiates him into the ways of war by ordering him to kill an engineering student with a machete. Uzodinma Iweala’s source novel, which has a different ending, was written in a made-up English idiolect of present participle verbs and inconsistently dropped articles, which is preserved in the movie’s dialogue and narration—a first-person literary device applied to a film that’s often too dour to get inside Agu’s head. (Beasts Of No Nation’s one attempt—a battle scene with a swapped color palette representing Agu’s disconnection from reality—is a fumble, resembling a drug trip sequence from a bad scare film.)

Fukunaga’s staging of attacks and skirmishes is confidently measured—a raid on a surveying convoy being a particular standout—and yet he never gives the violence and gore any weight. As a result, the assorted montages of downtime among the Commandant’s soldiers (playing blind man’s bluff, getting stoned, hunting cane rats for bush meat, etc.) seem less like oases or counterpoints than like longueurs. One could claim that the film is meant to present a perspective desensitized to violence—but then what is the movie sensitive to, aside from tastefully composing widescreen in thirds?

There’s a good argument to be made for mapping film history through images of hell, the medium maturing as the earliest of the early filmmakers went from filming places viewers would want to visit to filming ones that they wouldn’t, and eventually hitting upon the idea of making people look at things they didn’t want to see—but in order to envision hell, one has to be afraid of it, even if it’s only as a psychological state. The problem with Beasts Of No Nation is that it approaches war largely on the level aesthetic challenge, meaning that whatever sense of revulsion it creates comes from the personality of Commandant. It’s his absence, rather than memories of murder and rape, that hangs like a dark cloud over the movie’s intriguingly unresolved epilogue.