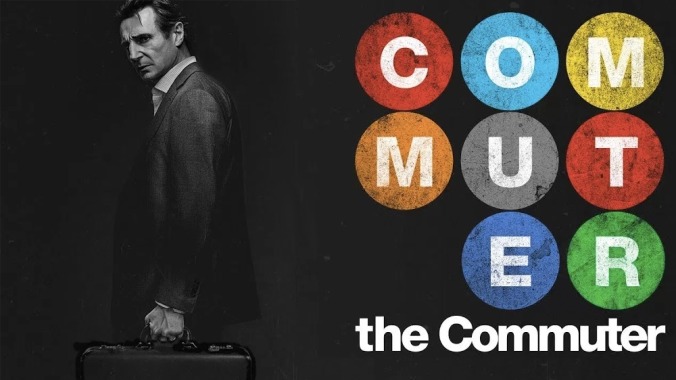

If only every January thriller were as smart-dumb as Liam Neeson's The Commuter

“On behalf of the American middle class, fuck you,” growls Michael MacCauley (Liam Neeson, obviously) not more than a third of the way into The Commuter, tipping the dizzying whodunit’s hand. Yes, it’s basically Non-Stop (also starring Neeson, also directed by the Spanish-born genre whiz Jaume Collet-Serra) on a train, the paranoid and ludicrous plot and compartmentalized, pop-psychological action played off as allegory. The earlier film poked fun at the post-9/11 surveillance state, with Neeson as an alcoholic air marshal framed for hijacking a plane. But this time, as they say, it’s personal: debt anxiety, the subprime mortgage crisis, the manipulation of class resentments by a conspiracy of The Game proportions. One of the modern Hollywood B-movie’s most technically proficient and politically astute directors, Collet-Serra keeps his camera zipping; it takes a climactic crash of fiery twisted wreckage—in which The Commuter literally jumps the rails—for his frantic twists and speed-addled Hitchcockian themes to lose momentum.

Most of Neeson’s post-Taken action and thriller roles have been ex-something-or-others, and MacCauley is no different, though he lacks the tragic backstory that have made so many of these characters into meditations on death and grief (The Grey, A Walk Among The Tombstones, Collet-Serra’s own Run All Night) that seem to be in conversation with the towering Irish actor’s real-life widowerhood. Instead, MacCauley’s regrets are more quotidian: He’s a former cop who gave up his badge because he couldn’t pay the bills and put his kid through college on an NYPD salary. Not that the career change did him any good. He’s 60 years old with two mortgages and no savings, commuting to midtown Manhattan on the Metro-North train to sell life insurance to suckers like himself. Laid off with no ceremony (his severance package, it turns out, is more insurance), MacCauley makes one last stop at a cop bar frequented by his old buddies to drink up the courage to tell his wife (Elizabeth McGovern) that he’s out of a job before getting on the packed train home.

The only thing the afternoon seems have in store for him is more white-collar frustration: the air conditioning is broken in one of the train cars, the police are checking bags at rush hour, and, worst of all, someone seems to have stolen his phone. But then a stylish mystery woman, Joanna (Vera Farmiga), slides into the seat across from him and strikes up an increasingly less hypothetical conversation that he at first misreads as flirting. What if there were $25,000 in cash hidden in the bathroom of the next car? And what if MacCauley had a chance to make another $75,000? The only thing he has to do is find another passenger on the train and hide a GPS bug in their bag. As for locating the target, that’s up to him, because all Joanna can tell MacCauley before disappearing is that he or she is going to a suburb called Cold Spring, and won’t be one of the regulars he’s used to seeing on his commute. The $25,000, it turns out, is real, but at this point it’s too late to back out of Joanna’s Hitchcock-inspired parlor game. (It’s a little Lifeboat, a little Strangers On A Train.) His wife’s wedding ring is in the package and a desperate attempt to get help has fatal consequences for one of his fellow commuters.

Mustering his rusty cop skills and insurance-sales smarm, MacCauley crosses from car to car, trying to identify the mystery passenger—striking up an impromptu card game with one stranger, telling the conductor that he’s meeting up with an online date, and so on—while he tries to figure out just what kind of preposterous set-up he’s found himself in. (At times, Neeson seems to be doing his best to channel Jimmy Stewart.) Collet-Serra’s camerawork is always creative with tight spaces, playing off their claustrophobia and urgency, but he goes wild here: Vertigo dolly-zooms; overhead shots; impossible, Panic Room-like camera movements through holes punched in train tickets; a digitally composited sequence of retreating dolly shots that maps the interior of the train car by car, akin to a similar sequence in Non-Stop; an extended single-take scene in which MacCauley wrecks the inside of an empty car while grappling with an assassin.

Signs and billboards make ironic comments (“See something, say something,” “You could be home right now,” etc.) as gangway connections between cars flex and obscure lines-of-sight. Progressively, the commuter train starts to resemble a funhouse, distorting anxieties; the characters can’t stop dropping references to the cost of education and the difficulty of retirement in today’s America, and even the aforementioned assassin admits that he’s only in this to pay off debts. One moment they promise you easy money, the next they’ve got your family. The Commuter’s script may not be an exercise in fool-proof logic (the actual plot makes almost no sense in retrospect), but its politics are consistent—a rare quality for a contemporary thriller. Given that this is the fourth film Neeson and Collet-Serra have made together, one can’t help but wonder what they’ll do next: A thriller set on a bomb-rigged Greyhound bus that doubles as a commentary on recidivism and the prison-industrial complex? Chunnel, an allegory for Brexit? Something with a boat?