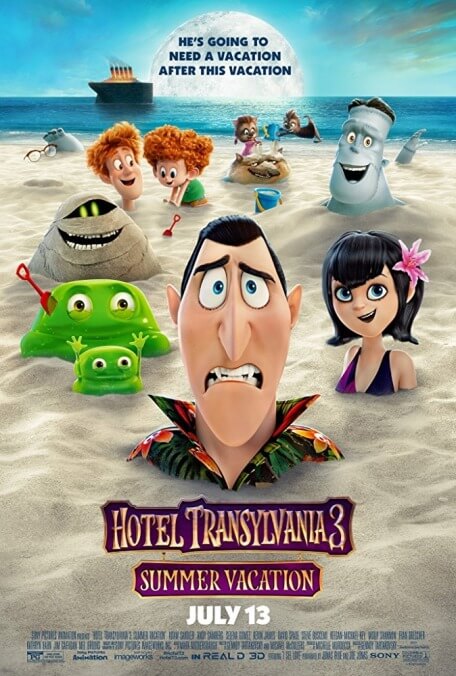

In the third installment of the animated franchise Hotel Transylvania, Dracula (Adam Sandler) takes a Bermuda Triangle-bound ocean cruise with his vampire daughter, Mavis (Selena Gomez), accompanied by the undead Frank (Kevin James), wolfman Wayne (Steve Buscemi), invisible man Griffin (David Spade), and mummy Murray (Keegan-Michael Key), among other monsters and creatures. Given the Halloween-centric origins of the earlier films, this change in location essentially makes Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation the Christmas Ape Goes To Summer Camp of the series, or perhaps the cinematic equivalent of “The Monster Swim.” With such unpromising origins, it’s pleasantly baffling to discover that not only is Hotel Transylvania 3 easily the best film of the series, but it also feels more at home thematically on a cruise ship than its predecessors did at a haunted Transylvanian castle.

This being a Hotel Transylvania movie, the characters remain as macabre as the Munsters; nothing here betrays a Tim Burton-like reverence for actual monster movies. What returning director Genndy Tartakovsky reveres is animation—and not necessarily the wonders of photorealistic follicle creation or impeccably rendered water, but the kind of gloriously exaggerated movement, the stretchy and springy caricature, that enlivens many classic cartoons. When Tartakovsky’s characters stomp around, their feet flap and bounce; when they argue, they coil and bend.

The previous Hotel Transylvania movies had this elasticity, but as the characters swooped from pose to pose, they also had to mouth sitcom-level jokes about fathers protecting their grown daughters’ purity and younger parents protecting their kids’ physical safety. Here, Dracula frets about growing old without a romantic partner (his wife died years ago), while Mavis worries that her working relationship with her dad running their hotel is cutting down on quality time. It’s not exactly a Pixar-level examination of complicated family dynamics, and the movie still has plenty of knuckled-headed, Sandler-style boys-will-be-dumbasses shtick: Children everywhere will surely thrill to the sub-subplot about Frank catching hell about his gambling problem from his wife, Eunice (Fran Drescher)! But mostly it’s a cute, functional story for Tartakovsky to enliven with his style.

That’s really where Hotel Transylvania feels liberated from its predecessors. Tartakovsky, receiving his first writing credit of the series (he’s working with Michael McCullers, who has extensive experience writing for both ex-SNL stars and cartoons), constructs gags based on visuals rather than dialogue, a seemingly rudimentary aspect of animation that many big-studio features nonetheless ignore for long stretches. Here, the animation drives characterization (Mavis sometimes moves just like her dad) and, in place of one-off gags, full comic sequences: a trip on a gremlin-run, monster-friendly airline; Wayne and his wife, Wanda (Molly Shannon), cavorting merrily after dropping their litter of puppies off with a babysitter; an exploration of an ancient booby-trapped vault that turns into a courtship dance between an impervious Drac and Ericka (Kathryn Hahn), the human cruise director he’s protecting.

Ericka turns out to be a descendant of the famous monster-hunter Van Helsing (Jim Gaffigan), introduced in a prologue and accompanying montage establishing him as the Coyote to Dracula’s Roadrunner, and then reintroduced as an old man kept alive by steam-powered parts, resembling a grotesque jack-in-the-box. He’s an amusingly creepy foe and a perfect vehicle for Tartakovsky’s wilder visual ideas, so it’s a shame that so much of the story involves Dracula understanding that Ericka inspires in him the elusive and much-discussed “zing.” (It’s described as a monster version of love at first sight, which is to say: when a monster falls in love at first sight, kind of like when that dude fell in love with a baby in Twilight.)

It’s one reminder among many that Hotel Transylvania 3 still operates within the limits of its series. Late in the movie, it seems like Tartakovsky is going to satirize some of his colleagues; Van Helsing hopes to lure the monsters to their doom with what is, effectively, a massive dance-party ending designed to go apocalyptically wrong. Then the movie gives up and leans into the hackiness with the extended use of a music cue so unapologetically terrible that’s almost (but not quite) punk rock. But if the movie’s technique is too good for this material, it’s also too good to be spoiled by garbage earworms. The movie zips so quickly and energetically from gag to gag, and so effectively improves on its own formula, that animation fans may zing, however momentarily.