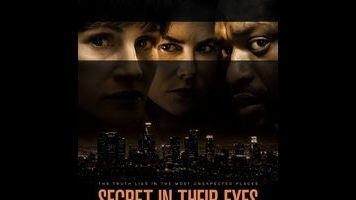

Improvements aside, Secret In Their Eyes is still a redundant remake

When it comes to remaking foreign films for American audiences, there’s apparently no such thing as “too soon,” and nothing so unbroken that it can’t be “fixed” by dropping the subtitles. See Oldboy. See Let The Right One In. Don’t see the competent but unnecessary do-overs they inspired. Secret In Their Eyes, a moody detective thriller about the present catching up with the past, finds writer-director Billy Ray (Shattered Glass) excising both a definite article and a decent chunk of overlong running time from the 2009 Argentinian Oscar-winner of (basically) the same name. There was certainly room for improvement, and this fairly speedy remake of a fairly recent import edges out its predecessor in just about every category except precedent. Yet nothing short of overhauling the material into something genuinely fresh could make Ray’s Secret feel essential. Tweaks aside, it remains, by in large, the same movie—which is to say, fundamentally redundant.

Thankfully, Secret In Their Eyes isn’t entirely the same movie, in the scene-for-scene, shot-for-shot manner of, say, Michael Haneke’s second Funny Games film. Changes have been made, beginning with the shrewd decision to bring the story’s whodunit closer to home: This time, the rape and murder victim is the teenage daughter of one of the law-enforcers, Jess Cobb (Julia Roberts). Cobb is part of a special anti-terrorism unit operating out of Los Angeles, and the fact that her only child is found in the dumpster next to the mosque they’re monitoring makes it fair game for her coworkers to involve themselves. Specifically, it’s moonlighting FBI agent Ray Kasten (Chiwetel Ejiofor, in the Ricardo Darín role) who starts digging, even after being told by his superiors that homeland security is top priority. Despite being a “blue-collar Fed from the wrong side of Brooklyn,” Ray can’t resist trying his luck with the new deputy DA, Claire Sloan (Nicole Kidman), an engaged Harvard grad who not only flirts with giving him the time of day, but also permits some of his outside-jurisdiction, cop-on-the-edge methods.

If all of this sounds a tad familiar, it’s because most of it has been recycled. Secret preserves the basic thrust of the original’s twisty plot, as well as its flashback structure, in which scenes of Ray hunting the prime suspect are intercut with the belated reunion of the principal players, estranged for 13 sleepless years. (At times, only the hairstyles betray which of the two timelines we’re occupying.) But there are smart deviations, too: Here, our sleuthing Fed isn’t writing a book about the cold case, but trying to reopen it—a change that allows Billy Ray to stage action scenes in the past and present. He also provides his haunted hero a sense of personal responsibility, a guilty conscience that better accounts for his obsessive devotion to the case.

Less interesting are attempts to invest the story with (sadly and suddenly topical) political context. Just as Juan José Campanella framed his film around Argentina’s devastating Dirty War, this Secret situates itself in a post-9/11, red-alert climate. As Ray discovers, the likely murderer, a sneering sociopathic punk played by Joe Cole, is also an asset of the state—a protected federal witness whose role as an informant is considered more important than his “love life,” to quote his scummy DA handler (Michael Kelly). Critiquing the mixed-up priorities of 2002 America is a solid agenda, but the fact that Secret can become a war on terror parable without much reconfiguring of its basic plot details suggests that the political framework is largely secondary, even interchangeable.

For all its minor course corrections, the film suffers from many of the same issues—the leaps of logic, the convenient coincidences—as its Argentinian ancestor; for example, an urgent chase through a sports arena (ballpark instead of football field) still hinges on an incredible spot of good luck, a needle being found in a haystick. At least the performers are game. Ejiofor brings both a fiery temper and a low romantic smolder to the role, doling out knuckle sandwiches when not exhibiting the same bone-deep longing he brought to this year’s Z For Zachariah. His top-billed costars, meanwhile, each get at least one standout scene—Roberts granted a wrenching Mystic River breakdown new to the material, while Kidman does wonders with the moment in which Claire basically dares the guilty party to confess to the crime to prove his manhood. But how much can they really do with a story that was just told, in more or less the same way, only a few years ago? Like their characters, the actors are trapped in a new drama that’s actually an old drama. The audience is trapped right there with them.