In 1962, the Williamsburg Bridge inspired a comeback—not indie, but Sonny

In Hear This, A.V. Club writers sing the praises of songs they know well—some inspired by a weekly theme and some not, but always songs worth hearing. This week, to honor Braid’s new record, we’re picking our favorite songs from “comeback” records.

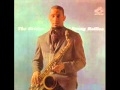

Three years might not seem like much of a hiatus for a musician to take, at least not by today’s standards. But in the early ’60s, three years was an eternity—especially for a jazz artist. Not only was the genre mutating at a dizzying rate as bebop began to morph into free jazz, but most jazz musicians recorded multiple albums per year. Take, for instance, saxophonist Sonny Rollins. Between 1953 and 1959, the contemporary of Miles Davis and John Coltrane released no less than 21 albums under his own name as a leader (one of them being 1958’s game-changing Freedom Suite). So when he announced his temporary retirement in ’59—at the ripe age of 29—in order to recharge his batteries after seven hectic years of runaway success and acclaim, it was a big deal. And it was an even bigger deal when, in 1962, he came roaring back with The Bridge.

That’s not to say Rollins’ saxophone itself roars on The Bridge. The album is a relatively subtle and meditative statement, which made it all the more striking in the revolutionary atmosphere of ’60s jazz. During his three years on the down low, Rollins spent long hours hanging out at the Williamsburg Bridge, gazing at the East River and pouring his heart out into his instrument for hours at a time. Rollins’ sound had always been gutsy yet supple, the standard for the hard-bop workouts that reigned throughout the ’50s. Searching for something more modern and intimate, he formed a new quartet—which made prominent use of master guitarist Jim Hall—that recorded a mix of standards and originals, including what would be become the title track of Rollins’ comeback album.

Like a runaway daydream, “The Bridge” is both frenetic and meditative, the sound of a scattered mind exulting in its own agility. Hall and Rollins trade solos like sparring tides; the rhythm section of bassist Bob Cranshaw and drummer Ben Riley lock into a fleet, liquid-tempo syncopation. But rather than trying to hop on the bandwagon of free-jazz abstraction, the Rollins composition reflects a very real set of coordinates in emotional space-time: when he stood below that bridge, day after day for months on end, pouring out his soul. What it must have been like to be a random passerby during those years, hearing the song’s embryonic skronk slowly coagulate into a masterpiece. Rollins’ break between ’59 to ’62 wound up being just the first of his many sabbaticals from jazz—but thanks to the soulful testimony of The Bridge, it remains his most legendary.