In 1992, Pepsi Fever turned deadly

We explore some of Wikipedia’s oddities in our 6,284,187-week series, Wiki Wormhole.

This week’s entry: Pepsi Number Fever

What it’s about: A contest where everyone was a winner… with tragic results. In 1992, Pepsi Philippines started printing numbers, 001-999, inside bottle caps, with numbers corresponding to prizes that were announced on TV nightly. It was a huge success at first… until a misprint put the million-peso ($40,000 USD) winning number on 800,000 bottles, resulting in rioting, lawsuits, and a massive debacle for Pepsi.

Biggest controversy: Those 800,000 winning bottle caps weren’t technically winners. Each contest bottle caps had a security code alongside the number for confirmation; the misprints had no code. But that mattered little to people who were convinced they had won. Panicked Pepsi executives held a 3 A.M. meeting and worked out a compromise, where the misprint bottle caps could be exchanged for a 500-peso ($18) consolation prize. Although 486,170 people accepted, it was a lose-lose for Pepsi. The payouts cost the company 240 million pesos ($8.9 million), on a contest that initially had $2 million USD set aside for prizes.

Strangest fact: Pepsi has a massively popular brand they sell everywhere except the U.S. The Number Fever contest included PepsiCo’s four biggest sodas—Pepsi, 7-Up, Mountain Dew, and orange soda Mirinda. While Coke has Fanta and Keurig-Dr. Pepper has both Sunkist and Orange Crush, Pepsi doesn’t have a signature orange soda in the U.S. The company started selling Mirinda in Spain in 1959, and it’s become a massive global brand, popular everywhere from Mexico to India to Egypt, and variants with flavors ranging from other citrus fruits to passionfruit, banana, hibiscus, and tamarind. Pepsi apparently attempted to push Mirinda in the U.S. in the ’70s, even commissioning Jim Henson to do a series of commercials with the Cookie Monster-esque “Miranda Craver.” But Mirinda seems to be the soccer of soft drinks, catching on everywhere but here.

Thing we were happiest to learn: The contest was initially a huge success. Pepsi had run similar promotions with great success across Latin America, and the contest got Filipinos excited enough that Pepsi’s market share went from 4% to nearly 25% overnight. (No word as to how far it dropped after disaster struck.)

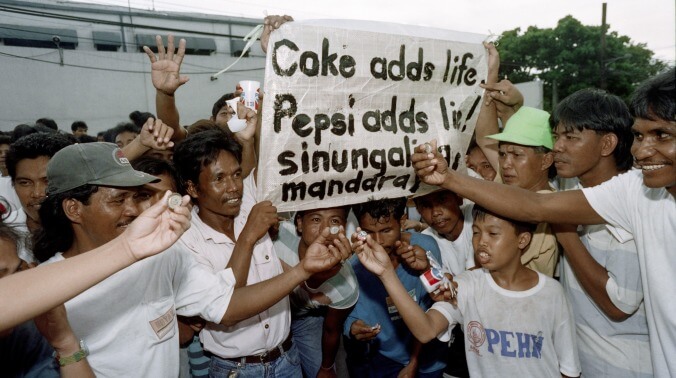

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: While some people accepted the consolation prize (and accepted an honest mistake on Pepsi’s part), some people were angry. And some people were very angry. Pepsi drinkers who felt they had been cheated formed a consumer group, the 349 Alliance (349 was the misprinted winning number), which organized boycotts, protests, and numerous lawsuits. In an sentence where the word “but” is doing some Olympic-caliber heavy lifting, “most protests were peaceful, but three [Pepsi] employees were killed by a grenade thrown into a warehouse in Davao, and a mother and child were killed… by a grenade thrown at a Pepsi truck.” Thirty-seven Pepsi trucks were “pushed over, stoned, or burned.” One sitting Senator suggested rival bottlers were behind the attacks; a popular conspiracy theory at the time was Pepsi itself staged the attacks to frame the protestors as terrorists.

Also noteworthy: The Pepsi Number Fever case went to the Philippines’ Supreme Court. Hundreds of civil suits and thousands of criminal fraud complaints were filed in the wake of “the 349 incident.” One court awarded plaintiffs 10,000 pesos each in “moral damages.” Three of those plaintiffs appealed for more money; the appellate court raised the award to 30,000 pesos. Pepsi then appealed that decision, and in 2006, 14 years after the initial incident, the Supreme Court ruled Pepsi was neither liable for the misprinted prizes nor further damages. And in a Simpson-esque “let’s never speak of this again,” touch, the Justices also ruled, “the issues surrounding the 349 incident have been laid to rest and must no longer be disturbed in this decision.”

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: While the 349 incident was a genuine accident, the Hoover Free Flights Promotion was just astoundingly poor planning. In the early ’90s, Britain’s ubiquitous vacuum cleaner company was being hit hard by a recession and competition from newcomer Dyson. So they ran a promotion in which anyone buying more than £100 worth of Hoover products would get two round-trip plane tickets to the U.S. Naturally, the plane tickets costs several times as much as the vacuum cleaner, and Hoover had to scramble to stop the already-out-of-control promotion. The British public viewed the promotion as “buy these incredibly cheap airline tickets and get a free vacuum cleaner into the bargain.” Hundreds of thousands of people took advantage, and neither Hoover nor the airline were prepared for the demand (the airline eventually folded). Hoover tried to make the application process for the airline vouchers as complicated as possible to dissuade people, but trans-Atlantic flights were going for £600, so £100 plane tickets and a free vacuum cleaner were too good a deal to pass up. Like Pepsi, Hoover lost their shirts and also angered the public when they tried to renege on the too-good-to-be-true giveaway.

Further Down the Wormhole: One of the two grenade attacks in the wake of the 349 incident took place in Manila. The Philippine capital was founded in 1258 as Maynilá, and has grown to be both the most densely populated city on earth, with 1.78 million people in 107,520 square miles, and also a sprawling metropolis, with a metro era of 12.8 million people. Among other things, the city hosts the country’s only sizable baseball stadium—Rizal Memorial. The sport was popular in the first half of the 20th century but has declined to the point where the country’s last professional league folded in 2012. But Filipino and American baseball share some history; the first two players to hit home runs at Rizal were Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth, on a world tour 1934. (The Bambino was at the end of his career, as he left the Yankees in ’34, playing a disastrous ’35 season for the Boston Braves that saw him retire by Memorial Day.) That season was largely forgotten by the time the Sultan Of Swat was inducted into the Hall Of Fame a year later, standing alongside some of baseball’s greats, including a previous star for Boston with a terrific nickname, Old Hoss Radbourn, a 19th-century pitcher who holds what’s considered baseball’s most unbreakable record. We’ll examine his astounding career on the field, and colorful exploits off of it, next week.