In A.I., Steven Spielberg (and Stanley Kubrick) turned an eye to loneliness

Image: Screenshot: A.I. Artificial IntelligenceGraphic: Jimmy Hasse

In the way music fans would describe themselves as Beatles people or Elvis people, for a time film buffs would categorize themselves as worshipping at the Church of Martin Scorsese or the Temple of Steven Spielberg. Today the distance between them has shrunk to the point that there’s not a stark difference between one’s auteurism and the other’s popular entertainment, leaving room for another friendly rival to serve as Spielberg’s mirror image: Stanley Kubrick.

The two were admirers of each other’s work, though a huge gap separated their styles and sensibilities. There’s Kubrick’s philosophical 2001: A Space Odyssey on one hand and Spielberg’s emotional Close Encounters Of The Third Kind on the other, or the cynical Full Metal Jacket versus the patriotic Saving Private Ryan. Were one forced to choose between them, it would be a choice between a detached analyst of the human condition and a humanist.

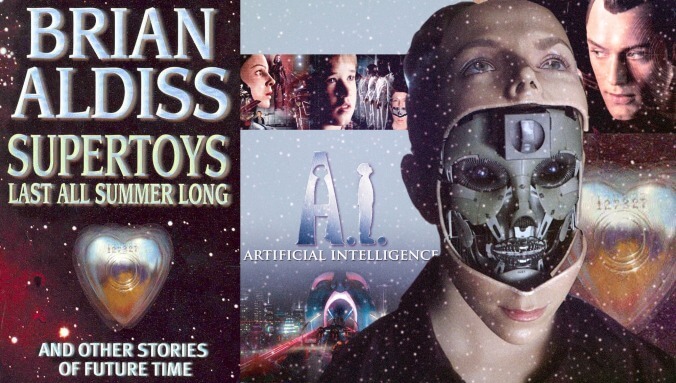

Nowhere do those divergent worldviews clash more visibly than with A.I. Artificial Intelligence, the film that was famously developed by Kubrick before his death and then passed to Spielberg to complete. This wasn’t simply a matter of Kubrick running out of time; he spent years working on the material with Brian Aldiss, who wrote the trio of short stories from the collection, Supertoys Last All Summer Long, that the film was based on. Ultimately it proved too tough a nut to crack. Kubrick couldn’t find a satisfactory way into this story of a robot child programmed to love, a premise pitched precisely at the Kubrick/Spielberg intersection of stoicism and sentimentality.

According to Aldiss, who reflected on Kubrick in a preface to a new edition of the short story collection, neither made it easy on the other. Aldiss was skeptical his “vignettes” could work as a movie and balked at the idea of turning the story into a sci-fi riff on Pinocchio, as Kubrick wanted and as the film eventually would. Instead, he pushed for Kubrick to create “a great modern myth to rival Dr. Strangelove and 2001,” one externally focused rather than concerned with the internal thoughts of a character—especially since the internal thoughts in question were artificial. Didn’t work. “I was wheeled out of the picture,” he writes.

Kubrick was famously a perfectionist, and the pre-production stalled as he found a reason to shoot down ideas or get sidetracked with harebrained schemes. (He debated having an actual robot “star” in the film and queried industrial firms about whether such a thing could be done. Hilariously, he called Mitsubishi, asked for “Mr. Mitsubishi,” and such was his renown that this worked: the CEO got on the phone.) Adding to the dilemma, A.I. is a project that rejects perfection, given the inherent contradictions in something fake feeling something real—or is that the other way around?

It should also be said that Aldiss’ stories didn’t give them a ton to work with, even accounting for Kubrick’s belief that it’s easier to flesh a short story out than it is to pare a novel down to feature length. The three David stories really are vignettes, adding up to fewer than 40 pages. So while there are feints to them in the film, Spielberg mostly invented things out of whole cloth. (A.I. is one of only two films where he has solo screenplay credit, along with Close Encounters. He’s one of three writers on Poltergeist.)

Each vignette cuts between David (played by Haley Joel Osment) and a parallel story involving one or both of his parents. In the first, “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” David plays with Teddy, an advanced Tickle Me Elmo, while his “mother,” Monica, uneasily watches him. Meanwhile, “father” Henry works at the robot-manufacturing company (they’re called “mechas” here) and talks about an upcoming model that will have “a controlled amount of intelligence.” The product is meant for companionship; a running theme of the trilogy is how, despite advancements that keep people fit or looking young, loneliness has become the scourge of the age. With mechas, “not only will [everyone] possess their own computers, capable of individual programming; they will be linked to the Ambient, the World Data Network,” Henry enthuses. “Thus everyone will be able to enjoy the equivalent of an Einstein in their own homes. Personal isolation will then be banished forever!” (As prognostications go, this is so close but so far.)

At the end of the story, a jubilant Henry and Monica learn they’ve been approved for reproduction, as the government has to sanction childbirths in this resource-starved future. It’s a twist ending, revealing David is a mecha (presumably an advanced model they got early access to) and not a precocious child.

“Supertoys When Winter Comes” picks up some time later. Henry’s become an even bigger wheel at the mecha factory and is about to close a deal that will make him the Mr. Mitsubishi of the industry. The job keeps him from home, where things have been rough. Their child died unexpectedly, and Monica is incapable of dealing with the grief. She posts anguished messages online, but the responders just want to argue or gloat about their unvarnished faith; no one offers sympathy or relief from her sorrow and loneliness. (This prediction was spot-on.) Her emotional state is only worsened by David, who both serves as a reminder of what she lost and is just off enough to be doubly unnerving (she prefers the comfort of a butler mecha who walks with a limp and is more convincingly human). In a fit of anger she tells David he’s a machine, which leads to a crash in his programming that manifests as a kind of tantrum.

“Supertoys In Other Seasons” jumps ahead again. Monica has died, and Henry, now CEO, is forcibly retired after algorithms disagree with an initiative to invest in Mars. David, we learn, was abandoned at some point, and spends his days in a sort of junkyard with other cast-off mechas, including the Dancing Devlins, a male-female pair that performs the same routine over and over again, always to David’s identical level of amusement. Without his job, Henry realizes he wasted his life pursuing professional success rather than emotional connections with his family. He tracks David down and re-adopts him, but David comes across other Davids, fresh off the assembly line, and has another crash as he realizes his true nature. Henry reboots the boy, clearing the memory and allowing him to live happily.

The first two stories, to the extent they have counterparts in the film, were adapted into the movie’s first act, though Spielberg fleshes out why Monica (Frances O’Connor) accepts David, why she “imprints” him by turning on the programming that makes him “love” her, and why she then abandons him. We learn she and Henry (Sam Robards) have another child, who is ill and in a medically induced coma until a cure can be found. As this seems unlikely, they’re in a kind of pre-grieving process, mourning a child who isn’t technically dead but with whom they can’t interact. When Henry has the opportunity to bring David home for a test run, he does so, viewing this replacement as a balm against their loneliness. While David doesn’t need to be raised, they can go through the motions with him; the first thing Henry does is get him ready for bed, even though he doesn’t sleep.

Monica is understandably aghast, both on principle and because David is so convincing as a human that it’s creepy. In the way people don’t want to ask their Alexas embarrassing questions, she doesn’t want David to see her use the bathroom or see him use tools that underline his artificiality.

Of course, he is a tool, and the job he was built for was to provide companionship. As such, Monica eventually warms to him, this adorable child who is programmed to behave and love her unconditionally, and she does the irreversible imprint. But then, a cure is found for her child, and David’s presence creates familial conflict upon the son’s return.

Henry wants David returned to the factory (read: destroyed), which under the circumstances is like asking Monica to shoot Old Yeller for accidentally biting her son. Because she can’t bring herself to end David’s “life,” she abandons him in the woods. This is one of Spielberg’s most affecting scenes, a new take on a theme he’s probed in some of his most intimate films. The plot of Catch Me If You Can is sparked by a divorce, and E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (his most personal film, and one referenced heavily by A.I., down to the structure of the titles) is also about a child wounded by a broken home. Such children often feel abandoned by their parents; there’s no divorce here, but that’s literally what happens to David.

From here the film is wholly original compared with the stories. David falls into—and escapes from—a “flesh fair,” a rodeo where mechas are destroyed for the amusement of people who feel displaced by automation. He meets Gigolo Joe (Jude Law), a sex robot who assists in getting David to a flooded Manhattan, where he will meet his creator (William Hurt). Here, as in Aldiss’ third story, David sees other copies of himself and reacts in anger. This is the only direct connection to “In Other Seasons,” though the junkyard there has elements of the flesh fair, and the Dancing Devlins seem to have inspired Joe by acting as warped robo-mentors.

Finally, and most controversially, David spends centuries at the bottom of the ocean, until an advanced form of mecha finds him and offers him the chance to be reunited with a reincarnated form of Monica for a single day. When the day ends, all human emotion is extinguished forever. Fade to black, and how.

These quests—everything from David being abandoned to the end of the film—is driven by the robot’s apparent belief in magic. Specifically, that Pinocchio’s Blue Fairy can make him organic, not mecha, which he sees as the impediment to his being allowed back in the house. It’s interesting this plot came from Kubrick, as Pinocchio is also a Spielberg touchstone; Richard Dreyfuss wants to take his kids to see it in Close Encounters.

That David believes in the Blue Fairy speaks to a fundamental problem with having a film led by machines, artificially intelligent or not, which is that they can’t both be robotic and function as three-dimensional characters. There’s inconsistency with what the mechas are able to do, think, and feel at any given time. David has protective safeguards, but he doesn’t know not to eat. A mecha at the flesh fair philosophically explains the humans’ hatred toward them as “history repeats itself,” then asks to have his pain receptors turned off. Teddy, after tumbling from a great height, comically mutters “ow,” suggesting he too feels pain (they’re supposed to register sensations for self-preservation, but why should they care if they feel a lot or a little?). Despite being the supertoy equivalent of a first-gen iPod, Teddy generally seems smarter than David, warning him, “You will break,” as he tries to eat. Was David intentionally developed to have the limited intelligence and emotional maturity of a child? If so, does that limit his other functions? Can Monica ask him to Google adult things? Can he not Google them himself? If he’s programmed with a database of knowledge, why does Robin Williams play a cartoon Einstein?

Questions about the nature of what’s real and artificial are at the heart of the story, both A.I. and Supertoys Last All Summer Long. Philosophy aside, what separates David’s feelings of love, the product of programming, from ours, the result of chemicals? “In Other Seasons” doesn’t see a difference; Henry insists that David only thinks he loves Teddy and Monica, but when David asks if Henry loved her, he sighs, “I thought I did.” Spielberg also sees David’s love as genuine, treating it with reverence.

The two are also connected by their focus on loneliness, which is the emotion that most lingers in the story’s wake. David is of course designed to be incomplete without his mother, but it’s sprinkled around other characters as well. Joe gets a ride by promising to introduce the adolescent boy drivers to a female sexbot, the “guiltless pleasure of the lonely human being”; we also see him tenderly seduce a bruised woman, who apparently needed romantic and physical affection in the same way Monica had maternal needs. Hurt’s character created David in the likeness of his deceased son; that he keeps his own replacement around is hugely revealing (and unspeakably sad). The vehemence on display at the flesh fair is driven by humanity feeling left behind.

There’s so much empathy for these characters, even as the coldness of life without love is underlined and underlined. Is that pairing Spielbergian or Kubrickian? How can it be anything but both?

Start with: It’s gotta be A.I., right? Not only are the short stories too thin to have much reaction to (though flipping through the rest of the collection is enjoyable), but this is also one of Spielberg’s most ambitious and visionary works, and one of the best from the point of view of pure filmmaking. Certainly it has a depth that seems unlikely to be matched by Ready Player One, his latest attempt at a sci-fi adaptation. It’s become commonplace to argue any flaws were due to his tendencies toward schmaltz, while the positive qualities were there from the start (as in, from Kubrick), but that feels like revisionist or unfounded criticism, particularly since Kubrick devised the Pinocchio thread. A.I. has its flaws—Spielberg is only human, you know—but it seems likely that as more times goes on, this will more clearly be seen as one of his major works.