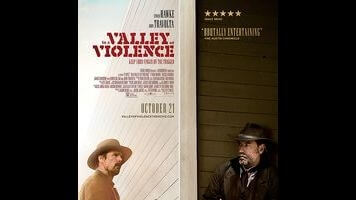

Denton, a dusty, one-saloon town that once served a silver mine, long since forgotten by both God and commerce. There’s a general store, an empty hotel (“the whores left with the silver”), and not much else to do, other than drink at that one saloon. This is the personal fiefdom of Clyde Martin (John Travolta, approximating a twang by talking like he has his jaw wired shut), a one-legged lawman who now keeps his badge in his pocket on account of the pin having broken off; his tendency toward long-winded speech suggests the symbolism of his station is not lost on him. But then in rides a bedraggled stranger (Ethan Hawke, committed as in all of his countless latter-day genre movie roles), accompanied by a dog. He gives his name as Paul, and in the space of about an hour, he manages to humiliate the marshal’s doofus son, Gilly (James Ransone), and make some small talk—small from his end, anyway—with the motor-mouthed hotel clerk, Mary Anne (Taissa Farmiga). And that just throws the shaky order of things in Denton out of whack.

From its cinematography (in 2-perf 35mm, Sergio Leone’s preferred format) to its Ennio Morricone-aping musical motifs, In A Valley Of Violence is as studious an exercise in homage as writer-director Ti West’s breakthrough, The House Of The Devil. Frankly, there’s nothing unusual about a horror director trying their hand at a Western. The two genres have a history of interchange, be it the influence of classic Westerns on the films of John Carpenter (who even penned two obscure Westerns, El Diablo and Blood River) and George A. Romero or the parallel development of the giallo and the spaghetti Western in Italy. There are plenty of hybrids, too, though they usually lean more into one genre than the other, with Bone Tomahawk and the under-appreciated Survival Of The Dead being the rare examples to have an almost equal footing in both.

But In A Valley Of Violence is very squarely a Western; it only hints at its director’s background in indie horror in a gruesome throat-slitting that happens late in the movie and an inspired sequence that unexpectedly applies the aesthetic of found footage to a flashback. If West has seen a single Western made before the 1960s, it doesn’t show—and given how proudly he parades his influences here, one has to assume that it would. He draws only on the violent and revisionist later entries in the genre (Leone, Sergio Corbucci, Clint Eastwood, Sam Peckinpah) to make a nihilist, heel-dragging black comedy that borrows its central conflict from John Wick. And maybe that’s part of the synthesis, too, given the role that cross-genre remakes—including Leone’s A Fistful Of Dollars, John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven, and Martin Ritt’s Outrage, all inspired by Akira Kurosawa movies—played in the era that Valley is going off of.

In A Valley Of Violence opens with Denton being cursed by a sham priest and climaxes with a man being beaten about the face and neck with his own boot, but its slapstick nihilism is completely meaningless. The paradox of Ti West is that the least interesting thing in his best horror films (The House Of The Devil, The Innkeepers) is the source of the horror, which tends to be unimaginative and non-metaphorical; a genre buff with no sense of an underlying unknown, he instead excels at mimicking aesthetic conventions, which he deforms for tension and disquieting effect. The Innkeepers, for instance, portrays the supernatural with all the originality and indelibility of a Halloween haunted house, but piggybacks off the aesthetic unease that comes with a ghost story to create a very closely observed portrait of friendship at a dead-end job.

But the conventions of the Western—even the ones that are very specific to a period—don’t work like the conventions of horror; they aren’t based on tone, which is actually why oaters hybridize so easily. So West is a literalist who has found himself in a genre of myth and allegory. He applies the same principles as in did in his best earlier films: a derivative premise played at face value, diligent imitation, protraction. (It takes half of the movie just to set up the conflict between Paul and the marshal.) But all that produces is a by-the-numbers spaghetti Western that’s kind of slow and uneventful—and the world has no shortage of those.