The Red Hot Chili Peppers are not a band known for their intellectual pursuits and good taste. Now in their fourth decade as California’s preeminent musical amusement park, RHCP have long since ascended to the rarefied air where bands concern themselves with things like trying to better society through clumsy social messaging and passionate pleas for world peace. And to be sure, the Red Hots are no different: They’ve played rallies for Obama and Hurricane Katrina, as well as the Tibetan Freedom Concert, and they were appearing in Rock The Vote ads as far back as 1990. But just as you can never put the toothpaste back in the tube, you can never really put the tube sock back in the drawer, which is unfortunate. RHCP’s longest-standing political commitment is to goofiness at all costs, and that’s obscured the depth of their playing. Go back and listen to “Give It Away” and hear the bass turn itself inside out around the groove, and tell Les Claypool to pack up his mustache and go home.

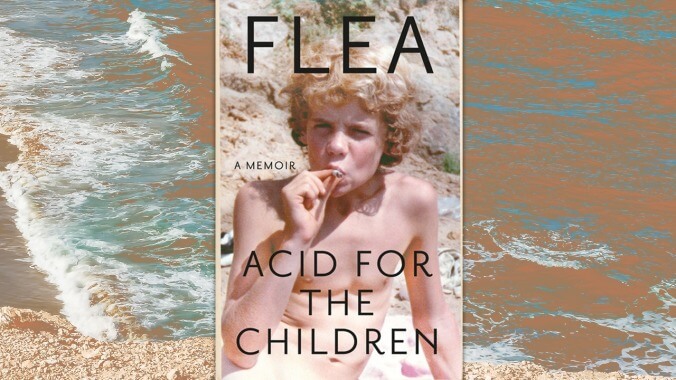

The man responsible for that bass line, of course, is Michael Balzary, better known as Flea. If Anthony Kiedis is the band’s masculine yang (a word he’s surely rhymed with “wang” at some point), Flea is their yin, the sneakily smart and sensitive one whose dedication to the low end keeps them grounded. And just as Kiedis’ 2004 memoir, Scar Tissue, was a super-horny travelogue of women against whose bodies the singer occasionally docked, Flea’s new memoir, Acid For The Children, is a gentle-hearted look at the relationships that formed and informed his earliest days. Fittingly, it ends the day after his first gig with Kiedis, guitarist Hillel Slovak, and drummer Jack Irons.

Flea is not shy about his ambitions. He told Entertainment Weekly that he hopes the book can “stand on its own as a piece of literature,” and in an appendix lists Michael Ondaatje, Toni Morrison, and Arundhati Roy as authors whose books “blew my mind.” Like the Beastie Boys in their recent memoir, he chops his early life up into vignettes, each of them so energetically told that they feel like they’ve been fired out of a cannon. Even at its most incisive and gutting—his examination of the effect his wounded upbringing has had on his behavior from boyhood to the present, his clear-eyed assessment of his mother’s decision to leave his father for a down-and-out jazz musician—the depth of feeling he lends keeps the story moving with the same kind of energy he brings to the stage.

Acid For The Children’s closest analog is, somewhat surprisingly, Patti Smith’s Just Kids. Just as Smith—who is a longtime friend and collaborator of Flea’s, and who provides the book’s foreword—captured the grimy intimacy of life in New York in the late 1970s, Flea’s manic prose recreates the wild L.A. streets of the same era. He and Kiedis roam Hollywood as unsupervised teenagers, riding midnight buses, jumping into pools from apartment roofs, shooting coke and later heroin. They are amoral fraternal chaos unleashed, two poles with a trip-line strung between them that bowls over everyone in their path. Upon bringing Kiedis into the narrative nearly halfway through, Flea tells us that “Anthony lived with the same fear and separateness that kept me totally disengaged from the social process… He went hard and challenged the external world. I went hard the other way, slipping deeper into an interior world.”

While the relationship between the two musicians should form the emotional crux of the story—“I think if I really understood it, the cosmic energy might leak out,” he writes of its complexity—the book’s pithiness keeps it from truly lifting off. This early chapter is the last time Flea writes with any depth about what he considers one of the most profound relationships of his life. Smith recognized that her early years couldn’t be understood apart from her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe, and her patient remembrance of the complexities of their time together is why Just Kids so affected people who never owned a copy of Horses. By front-loading the way he feels about Kiedis, thoughtfully written though it may be, Flea never allows us to see the complications in their relationship play out over time. It’s a disappointment, especially because Acid For The Children suggests he’s both talented and empathetic enough to give their story its due.

Flea can be maddeningly uneven on a sentence level, too. In the book’s opening chapter, he writes lyrically of how a recent trip to Ethiopia returned him to the root of his motivations as a musician, and about the “burning thing inside me that has kept me always curious, always seeking, yearning for something more.” In the same chapter, he makes reference to “the godzzz,” uses a six-period ellipsis (twice!), and offsets the phrase “boom bap boom ba boom bap” into its own paragraph. The prose frequently mimics his playing: occasionally beautiful, occasionally outrageous, in conversation with a small group of predecessors but unwilling to follow anyone else’s rules.

This is what gives Acid For The Children its considerable charm, and Flea knows it. And it’s worth asking whether 400 pages of sober and reflective storytelling is what we want from the dude who played Woodstock ’99 naked. Taken on its own terms, Acid For The Children feels remarkably close to the bone, its author nuanced in his understanding of himself, his hang-ups, and his surroundings. “I may well be… an uneducated animal who runs on instinct and feeling,” he writes. “But this is my voice.”