In his final months, Pedro Zamora turned The Real World into an educational platform

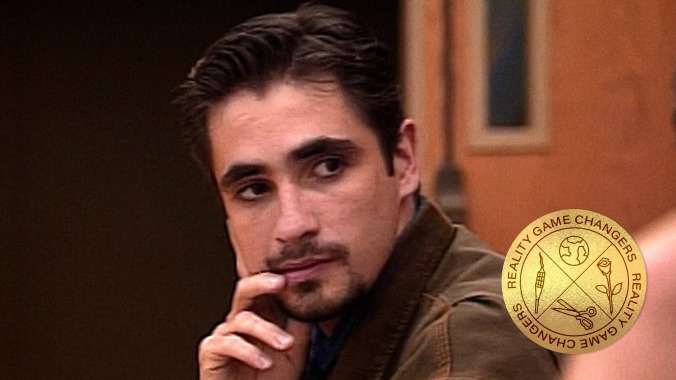

Image: Screenshot: The Real World

AIDS activist Pedro Zamora spent the majority of his time on The Real World: San Francisco, which ran from June 30, 1994, to November 10, 1994, educating others. Whether he was giving a lecture in a classroom, casually discussing his health with his partner—the late Sean Sasser—over dinner, or in the throes of yet another battle with his roommate David “Puck” Rainey, the passionate 22-year-old Cuban American never shied away from sharing his full experience as a person living with the disease. Even in his final moments, Zamora considered educating the masses his dying duty, a parting obligation in the fight against both the continued ignorance surrounding HIV-AIDS as well as the disease itself. In doing so, he put a personable, human face to an epidemic that was still largely considered a medical mystery more than a decade after the first reported cases in the U.S. It’s part of what ultimately made him one of the fiercest AIDS educators in the movement, an immovable figure in MTV’s reality TV legacy, and a TV pioneer in his own right.

With its series debut in May 1992, The Real World set the foundation for the modern reality genre. At first glance, the idea of filming seven strangers as they lived together in a swanky loft doesn’t ring as the most exciting concept. But in its halcyon days—before sex, spectacle, and melodrama rose to its currently perceived level of necessity within the genre—a few cameras and a group of very different personalities generated enough excitement to pilot a franchise. The Real World was a relatable microcosm of the viewing generation: Each housemate was a conduit for the decade’s most prominent attitudes toward race, politics, religion, sexuality, romance, and pop culture. That alone was enough to attract the tension and chemistry that later seasons and other shows like Survivor and Big Brother attempted (and oftentimes failed) to duplicate. Still, nothing else has managed to capture the grounded essence of The Real World’s earlier incarnations.

The Real World: San Francisco proved to be as fresh and down-to-earth as its predecessors, centering on a house full of notable archetypes: Pam Ling, the busy med school student; Judd Winick and Mohammed Bilal, the scrappy creatives; impressionable college student Cory Murphy; rebellious young Republican Rachel Campos; and Puck, the brash, unpredictable slob. Even Jo Rhodes, who arrived late in the season after Puck was kicked out of the Lombard Street house, seemed to represent the college-aged woman in search of stability during her short stint in the house.

But it was Zamora, first seen surrounded by family at a lively going-away party in Coral Gables, Florida, who struck the strongest chord with the audience. He was warm, pensive, kind, and willing to share the more private parts of his existence with the world. It was the two most intimate aspects of his life—his health and his relationship—that made him a trailblazer both within and outside The Real World franchise: Zamora was the first castmate openly living with AIDS, and, alongside Sasser, one half of the first-ever couple to have a same-sex commitment ceremony on television. Over the course of 20 episodes, the educator didn’t just navigate his new home; he used his platform to both actively and inadvertently dispel the stigmas that often surround HIV-positive individuals and queer identities. As is the case with many visible members of marginalized groups, Zamora became a compassionate, familiar face to the sheltered weekly viewer.

For those who were even tangentially familiar with aspects of his daily experience, Zamora painted a relatable picture of the very specific burden that comes with existing in spaces majorly occupied by the status quo. As he faced “jokes” about his queerness, he also endured the silence of certain castmates who failed to intervene on his behalf. He also dealt with commentary regarding his romantic relationships, bigoted scrutiny over his disease, and former allies who seemingly sided with (or simply failed to totally condemn) aggressors like Puck, who often hurled homophobic insults in Zamora’s direction. Situational apathy is as prevalent a factor in the lived experiences of marginalized people as overt bigotry, and watching Zamora expose the true harm of indifference remains especially relevant today as the most vulnerable communities are continuously harmed by white supremacy.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Zamora was diagnosed with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a rare and incurable virus. As he began to gradually lose his faculties, the country grew increasingly invested in his condition—so much so that then-president Bill Clinton called Zamora’s family home where he was receiving care to check on him and express his gratitude for all of his altruistic work. When Zamora died in the early morning of November 11, 1994—mere hours after the season finale of San Francisco aired—the collective mourning stretched beyond his MTV audience. His mission to educate the masses also continued beyond his death. His former roommates Winick and Ling continued to lecture in his memory. Winick distilled his eye-opening friendship with Zamora in a graphic novel, Pedro And Me. Zamora’s sister Mily became a public speaker in an effort to continue his AIDS education. A number of foundations and funds—as well as a clinic—were established in his name.

It’s unfair that Zamora shared his final months with us at the ultimate expense of his health. But in the MTV memorial special, Mily shared that her brother pursued a spot on The Real World because he felt it was his only opportunity to reach the world. Among many things, Pedro Zamora represents the inherent power of reality television when it chooses to tell deeply human stories.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.