In his new memoir, even David Lynch doesn’t try to get inside David Lynch’s head

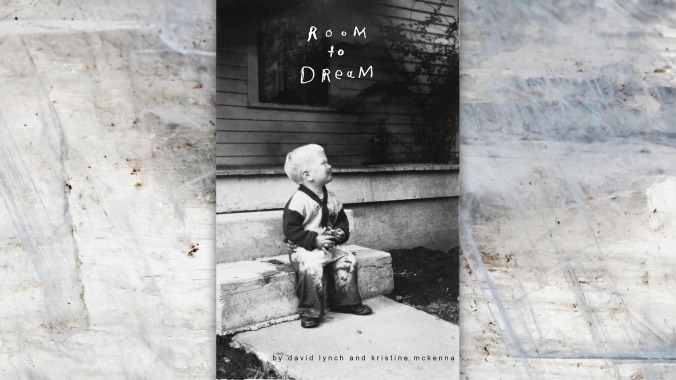

“It’s impossible to really tell the story of somebody’s life, and the most we can hope to convey here is a very abstract ‘Rosebud,’” David Lynch writes near the very end of Room To Dream, marveling at the failure of the preceding 500 pages to truly capture him. This is the inevitable upshot of all biographies, of course, and especially true when it’s a subject—and storyteller—like David Lynch, an artist who ambivalently resists all analysis, whether of his work or himself. The central conceit of Room To Dream is that, at last, Lynch will be the one doing the delving, with journalist Kristine McKenna providing objective (if clearly enthusiastic) reporting on some chapter from his life, immediately followed by Lynch offering first-person commentary and his own recollections. But because this is David Lynch, by the end of it all, Lynch remains elusive, even to himself. If Room To Dream is a Rosebud, then reading it is often like Charles Foster Kane repeatedly popping in to shrug that lots of kids have sleds. Y’know, maybe it was just a really good sled.

McKenna has conducted numerous interviews with Lynch over the years, and it’s easy to see why he trusts her. A journalist who’s also an art curator, she gives equal weight here to all of Lynch’s works—his painting, photography, music projects, and internet tinkering all get the same consideration and page space as Eraserhead and Twin Peaks—and like Lynch, she’s fascinated by process. Her chapters offer an acute, often-granular focus on production design, monograph-worthy descriptions of the meticulous aesthetics of Lynch’s films, a complement to Lynch’s own fixation on details. As with every Lynch profile, the portrait it paints is of a filmmaker who knows no greater joy than when he is knocking down walls with a sledgehammer, painstakingly mixing lipstick shades to get the perfect color, or—as Blue Velvet editor Duwayne Dunham recalls, in one telling anecdote—on his hands and knees, placing dust bunnies beneath a radiator, “just in case the camera might pick them up.”

Throughout, McKenna also provides a keen assessment of the prevailing themes of Lynch’s work: the duality of self; the mysteries lurking beneath the placid surface of suburban America; his fixed, thoroughly 1950s teen ideas of “cool,” rebellion, and love as, in McKenna’s words, “a state of exaltation.” But like Lynch, she’s far more interested in how these themes are expressed, rather than why Lynch might want to express them. And she also primarily lets others do the talking, the history of each individual project unfolding via interviews with a decades-long list of collaborators, admirers, roommates, assistants, and ex-wives—all of whom speak of Lynch reverently, if from a certain acknowledged distance (even the ones who married him).

While having Lynch immediately counter their tales with his own recollections suggests a potentially combative dialogue—as did Lynch’s preemptive declarations that this book would finally clear up all the “bullshit” written about him—he proves far too Zen for that. Even on the very rare occasion when his version differs from others’, he simply says he doesn’t recall it that way and moves on. Writing in his conversationally folksy, discursive manner, full of frequent digressions on restaurants and rock music, Lynch stays well above the fray—diplomatically glossing over the failure of Dune and instead lionizing producer Dino de Laurentiis, for example, and pointedly never really discussing his love life at all, even as former paramours like Isabella Rossellini talk about how much he broke their heart. “Marriage doesn’t fit into the art life,” Lynch writes at one point, and that’s more or less all he has to say about that.

He’s far more comfortable when he’s talking about others, whether it’s singing the praises of myriad actors and engineers (“I just love him/her” is a constant refrain), or telling talk show-ready anecdotes about kissing Elizabeth Taylor, or Harry Dean Stanton’s peculiar sense of humor, or his bizarre video shoot with Michael Jackson, or the several meetings he had with Marlon Brando during the zero-fucks, constantly-eating twilight of his career. Naturally, he brings it back to the Maharishi at every opportunity; the book practically doubles as a brochure for the benefits of transcendental meditation. It’s all part of Lynch’s humble self-assessment as a near-passive vessel, a conduit for the universe’s ideas, and he passes through these Hollywood tall tales of hanging with Fellini and The Beatles as much awed observer as participant, attributing his own successes to fate and the serendipitous intervention of others while shrugging off the notion of his own celebrity. “What is fame, anyway?” he asks rhetorically. “Elvis was famous.”

The slight disadvantage faced by Room To Dream is that—even without Lynch’s charming interjections—most of this stuff has been documented before in the many biographies, magazine articles, scholarly papers, and other profiles that have appeared over the decades, and often with greater specificity. Last year’s Lynch-narrated documentary The Art Life is a more candid and, ultimately, more illuminating look at the director’s white-picket-fence, Eagle Scout upbringing and his early, formative years in the grime of Philadelphia. Both Chris Rodley’s Lynch On Lynch and Dennis Lim’s David Lynch: The Man From Another Place dive deeper into the making and meanings of his films. And of course, Lynch’s own Catching The Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, And Creativity contains nearly all he cares to reveal (or can articulate) about his methods. In comparison, Room To Dream often feels slightly breezy, bustling through the making of something as complex and wondrous as Mulholland Drive in the same 30-page allotment devoted to the creation of his website, while Lynch goes off on tangents about the unfortunate dominance of genetically modified corn.

But as the most comprehensive picture of Lynch’s career so far—it ends with the making and immediate aftermath of last year’s Twin Peaks: The Return—it also offers a more accessible, digestible version of an artist who’s so admirably resistant to being abridged. And besides, as in all of Lynch’s work, the things that remain unsaid are part of the appeal. The title refers to Lynch’s oft-repeated maxim that stories should leave “room to dream,” to not spell everything out and just let the mysteries be. For Lynch, that’s true even when the story is his own.