A Who’s Who of movie-buff directors (David Fincher, Wes Anderson, James Gray, Richard Linklater, Arnaud Desplechin, Martin Scorsese, etc.) schmoozes about one of the few really essential books ever published about film in Hitchcock/Truffaut, a snappy talking-head documentary by critic and New York Film Festival head honcho Kent Jones. The book in question is François Truffaut’s Hitchcock (usually called Hitchcock Truffaut), an ungainly film-freak totem with the approximate dimensions of a ream of A4 paper and a cover that is both iconic and kind of ugly, being just the two names side-by-side in Helvetica, colored in with a tacky gradient and set against a background best described as “college physics textbook gray.” It’s the kind of book that looks important and very serious even if you don’t know why, poking obtrusively out of shelves in the publishing equivalent of a plain wrapper, decorated only with the ominous words, “revised edition.”

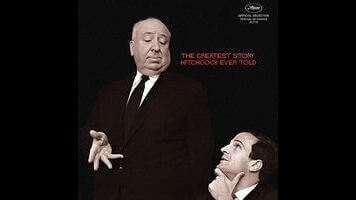

The thing about Hitchcock, though, is that it’s the breeziest of the big film texts, and one of the easiest to get sucked back into—an interview edited like a monograph and organized like a reference book. Truffaut, whose debut feature The 400 Blows was one of the breakthroughs of the French New Wave, had been a full-time director for all of three years when he sat down with his idol in a wood-paneled office at Universal Studios to talk about every movie Hitchcock had made up until that point and—based on the photographic evidence—smoke like a chimney. Before The 400 Blows, Truffaut had been known as a critic, part of a group called the “Hitchco-Hawksians,” on account of their constant stumping for Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. All Hitchcock had to bring to the conversation was himself, while Truffaut supplied an opinionated fan’s mindset and a real curiosity about what made his favorite movies tick. The result is still the best introductory text there is about the ins and outs of film as a popular art form.

What Jones does is respect the ease of the source material, in which heavy ideas about how and why we watch movies are carried along by the flow of conversation. Doing double duty as an updated companion piece (for those who already know the book inside and out) and as a foreword (for those who don’t), Hitchcock/Truffaut packs plenty of cogent observations into a modest package, but avoids turning into a Cliff’s Notes version of the book, instead using it and its history as a jumping-off point for new insights. Directors who know their stuff are some of the sharpest critics around, and here they get to gab about Hitchcock and Hitchcock, which is another way of saying that they get to give their own takes on the most primal and essential qualities of the medium, illustrated with clips and animation. (David Fincher proves to be the sharpest.) Though smarter visually than its TV-ready format would suggest (the camera team includes ace cinematographers Eric Gautier and Mihai Mălaimare Jr.), Hitchcock/Truffaut doesn’t offer a whole lot more than the opportunity to watch and hear very smart people talk about something they know very well. However, as its namesake’s decades-long legacy has proven, something as simple as that can be a treat.