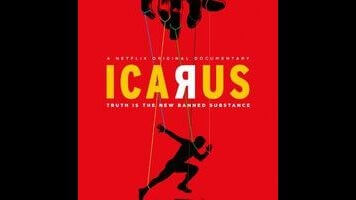

Bryan Fogel’s Netflix documentary Icarus tells such an eye-opening story that it almost doesn’t matter when the storytelling itself gets a little sloppy. An actor and playwright best known for the comedy Jewtopia, Fogel is trying his hand at feature-length non-fiction filmmaking for the first time with Icarus, and he just happened to stumble onto the kind of relevant, ripped-from-the-headlines scandal that investigative journalists spend years trying to dig up. What starts out as a Super Size Me-esque stunt—with Fogel injecting himself with performance-enhancing drugs to compete in an amateur cycling race—becomes a wider-ranging exposé of doping in organized sports. And then it takes a darker but in retrospect inevitable turn, as the filmmaker’s foray into the shady world of PEDs brings him into contact with a network of Russian scientists who’d rather not get caught on camera.

There is at least one Russian in Icarus who’s happy to talk, though—and thank goodness for that. Fogel’s odyssey begins when a disappointing result in a cycling competition gets him thinking about Lance Armstrong, and the widespread contention that every champion-level international athlete today relies on a chemical advantage while the organizations set up to police sports have been well-compensated to look the other way. He tries to find someone who can show him how the system works, and ends up befriending the gregarious Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, a director in Russia’s ironically named Anti-Doping Center. Funny, frank, and full of life, Dr. Rodchenkov immediately becomes the star of Icarus.

Roughly the first third of Fogel’s documentary is about his self-administered PED program, and how well it works—or in his case, how poorly. One of the reasons why Icarus feels clumsily constructed is that the project seems to have changed on the fly, after the director’s original plan went awry. There’s very little in the film’s early sections about the physical effects of injecting banned substances, or how it might help someone win a bicycle race. Instead, Fogel ultimately fumbles in his big cycling event for a variety of reasons, including mechanical failure. And before he has the chance to try and amp up his doping program, Dr. Rodchenkov gets embroiled in a scandal that changes Icarus’ focus.

What happens is that the story breaks worldwide about Russia’s Olympic officials and political leaders allegedly conspiring to foil the World Anti-Doping Agency by substituting clean urine for PED-tainted urine during the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. The methods uncovered by the investigators are a lot like the ones that Dr. Rodchenkov has taught to Fogel. So the filmmaker helps his best interview subject come clean, inviting him to come stay with him in the United States while he tells all he knows to the press and to law enforcement—including his implication that the Anti-Doping Agency itself has been corrupted.

No one can say that Fogel doesn’t have the goods. Dr. Rodchenkov was in deep with the Russian PED scandal, and Fogel was filming him way before the world at large knew his name. As the scandal escalates, there are cameras in the room as the doctor’s credibility and fate are discussed at the highest levels.

The main issue with Icarus is that the filmmaker struggles with how to present this wealth of material (much of which was just handed over to him), and how to connect it with the point where his documentary begins. There’s a lot that could’ve been said here about why athletes cheat and what effect that has on international sports. There’s even more to be said about whether we’re living in a world where everyone’s on the take, and where only personal charm and PR spin distinguishes one criminal from another. (What the film could use a lot less of, on the other hand, are the scenes where Rodchenkov reads aloud from George Orwell’s 1984.)

But while the movie does feel at times too much like an info-dump, the information itself is so astonishing that it survives the shambling approach. What’s most chilling—especially given recent political events around the world—is how aggressively the Russian government and media moves to badmouth Rodchenkov and suggest an alternative narrative for what happened in Sochi. From the point of view of the Putin government, this is all overblown Russophobia, relying on inconclusive evidence provided by an unreliable, disgruntled individual.

From Rodchenkov’s perspective, though, he has participated in fostering what is fast becoming a post-fact era, and his efforts at bolstering Russia’s athletic profile helped revive Putin’s then-flagging public approval ratings. He appears to feel bad about this—it’s just unclear how much. He never quite loses the winking “we’re all in the muck together” attitude he has when he first meets Fogel. As he helps the filmmaker break the rules, he says, “You are you what you are, I am what I am.” If Icarus’ vision of sports and politics holds true, that expression of cheerfully indifferent amorality could become the slogan for the 21st century.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.