Summertime means tentpole movies galore, with cineplexes dominated by high-octane action flicks and superhero fare. But there are always some wildcard films and directors that like to mix things up and keep audiences on their toes through complicated plots that require a little work on the viewer’s part. (We’re looking at you Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One and Oppenheimer.)

And that’s a good thing.

There’s nothing wrong with escapism, of course. But some filmmakers like to take labyrinthine leaps to make us think. These artists trust in our intelligence and our ability to sort things out, to dig into the themes, to dissect the symbolism, to be open to new ideas, and to think for ourselves. They don’t believe we need to be spoon-fed answers to the questions raised by their work., and sometimes that means invoking a fresh perspective on a familiar subject. It can be rewarding to have your expectations usurped and conventional wisdom challenged, giving you something to debate afterward.

In an era dominated by tweetstorms, Instagram reels, and other social media bombardment, people have become adept at juggling multiple threads and processing information more quickly. So there’s a joy to be found in taking a difficult movie—with more subplots and supporting characters—and trying to solve its puzzles.

How much plot can the audience handle?

Directors Christopher Nolan and Darren Aronofsky love playing with audience expectations and pushing the envelope. Nolan in particular imbues big-budget movies like Inception, Interstellar, and Tenet with an intelligence and sophistication that is often missing from many other tentpoles. That’s not to say that people who make blockbuster fare aren’t smart, but many simply assume their audience can only handle so much. But one can go back and re-watch Interstellar or Aronofsky’s Requiem For A Dream and find new things to appreciate about them with each viewing.

Aronofsky purposefully left much of The Fountain—a film with three interwoven storylines—open to interpretation, although he has also stated that it’s like a Rubik’s Cube where there are multiple ways to solve it but only one solution in the end. By contrast, surrealist filmmaker David Lynch is known for disrupting traditional narrative ideas and creating his own paradigm in which characters and audience members frequently question what is being experienced. The characters and audience essentially become one.

There are also films that, in contrast to the titles above, are seemingly simple yet have multiple ideas churning beneath the surface. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) seems to be about an alien monolith influencing the course of human history. Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) seems to be about a photographer who lives a uselessly anarchic life. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) follows a tour guide leading people into a contaminated no man’s land to a room that will seemingly grant wishes. All of these movies look to have very straightforward plots (although Blow-Up feels plotless at first), but the deeper you go into them, the more complex they become and the more you realize you don’t fully know what’s going on. You can respond by either checking out of the movie completely or reaping the rewards of spending hours debating them.

Movies change as viewers change

This writer saw 2001 for the first time when he was only eight years old, initially stunned by the imagery, music, and sound design. But successive viewings across multiple decades and with increasing maturity have led me to keep marveling at not only how well it is made, but how it views intelligence and evolution from different perspectives. The idea of whether human and artificial intelligence can fluidly co-exist takes on much deeper resonance now.

Today, there is a temptation for many viewers to search on Google or YouTube for the “explanation” of a movie ending. But that’s assuming that interpretation is correct. And sometimes endings, like Inception and its famous spinning top, do not provide the closure that people crave. Being confronted with a piece of art that makes us work has its merits, and when the screen goes dark and the lights come up, it allows ideas to linger in our brains long after the final frames have flickered away. You don’t need all the answers laid out. The joy in such films is that they can vary based on personal interpretation, while some fans can find common ideas to plug into.

For many people, such efforts are intellectually exciting. A time-bending movie like Donnie Darko (2001) and dystopian sci-fi fare like Brazil (1986) and Snowpiercer (2013) take us into worlds that were disturbing and confusing upon their release, yet now resonate more strongly with modern times.

The promise of a perplexing premise

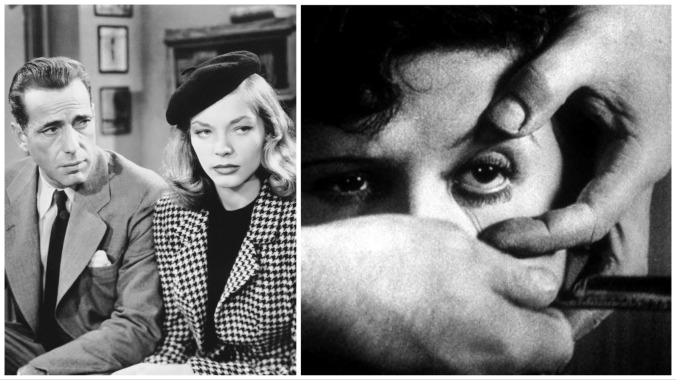

Stimulating an audience with a perplexing premise is nothing new in cinema. Surreal short films like Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) and Maya Deren and Alexandr Hackenschmied’s Meshes Of The Afternoon (1943) pushed boundaries in their day, while the seemingly more conventional 1946 film noir classic The Big Sleep, directed by Howard Hawks from Raymond Chandler’s baffling novel, had plot twists come so fast and furious that even today you need a pencil and paper to map out what’s going on. Four years later, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon dissected the concepts of memory, honesty, and truth in exploring conflicting viewpoints of a samurai’s murder.

One could argue that Inception and The Matrix feel like art films masquerading as sci-fi shoot ’em ups. Sure, you can enjoy characters firing guns and blowing stuff up, but the stories themselves are rooted in deeper philosophical questions that lured in viewers who don’t generally enjoy such genre fare. And people still talk about those films, dissecting their plots and wondering what it all means. And guess what? Both movies have made boatloads of cash and have long endured on home video and streaming services. That’s a win-win for everybody. And as long as viewers remain open to the joys of having to dissect, consider, and deconstruct a difficult film, those wins will continue—for the studios and, more importantly, for us.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.