Balancing narrative momentum with thematic ambition is harder than it looks, and it’s what makes James DeMonaco’s screenplay one of the stealth MVPs of the year. (He also directed, as he did for The Purge and The Purge: Anarchy). His script is admittedly rough around the edges—the dialogue is perfunctory; the characters are more archetypal than fully fleshed out, although there’s an elemental power in that—but few studio releases in 2016 felt as immediate or ripped from the gut. In an age of Hollywood timidity, Election Year stands as one of the ballsiest wide releases in recent memory, a subversive hit that delivers on the ass-kicking front while never glorifying that violence. This is exactly the kind of bold vision the Academy should recognize, and has before, with the dystopian allegories Children Of Men and District 9 both getting nods in recent years. (Due to an Academy quirk, Election Year would vie for Best Adapted Screenplay, as sequels are “based on” previous entries, which explains why the otherwise-original Toy Story 3 and Before Midnight competed in that category.)

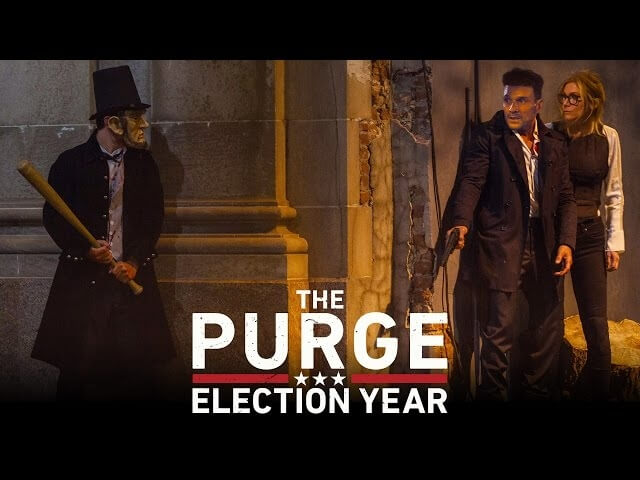

It’s a measure of the series’ effectiveness that the idea of a “purge”—an annual half day where all crime is legal—has taken on a life of its own in the broader pop culture arena, including a bizarre film of fan fiction/spoofery. But for the uninitiated, this entry centers around Charlie Roan (Elizabeth Mitchell), a presidential candidate running on a platform of dismantling the yearly bloodbath, which inevitably has a disproportionate impact on the poor and minorities. She’s opposed by the members of the New Founding Fathers Of America, a ruling class that uses the Purge to murder its enemies and extinguish as many “undesirables” (read: welfare recipients) as possible. After surviving an assassination attempt, Roan and her bodyguard (Frank Grillo) seek shelter in a convenience store and eventually connect with an underground resistance movement determined to overthrow the NFFA by any means necessary.

The parallels to the real world are self-evident, with the Purge serving as a metaphor for a society where the poor lack the protections of the wealthy, where minorities can be killed without consequence, and where people take to violence at the slightest provocation. Meanwhile, the film’s resistance group recalls a more militant Black Lives Matters; there are Purge enthusiasts who suggest a hybrid of the militia and white nationalist movements (some mercenaries sport Nazi tattoos, while there are lynchings and “murder tourists” from totalitarian states stirring up the American chaos); and a shadowy cabal of elites who pledge allegiance to the democratic process in public while using nefarious means in private.

But Election Year’s script doesn’t deserve recognition simply for its relevance, or because it offers more to think about than the category’s typical prestige winner does. It deserves it because of how cannily it’s constructed, both using and subverting traditional action-movie beats to its advantage.

Consider a scene that occurs midway through the film, when the convenience-store crew is threatened by a trio of criminals. Genre formula dictates that these three, who had been introduced as adversaries in an earlier scene, will stick around until the climax, or at least last for a lengthy action sequence, culminating, no doubt, in the proprietor (Mykelti Williamson) taking out the main criminal (Brittany Mirabile). Instead, the scene ends abruptly and unexpectedly, and the narrative zag at this moment reinforces the brutality of the film’s world while underlining the kind of moral compromises the characters are forced to make for their safety. It’s a canny counterintuitive move: By swiftly dispatching the threat, instead of building to a protracted battle, DeMonaco makes the Purge feel more dangerous.

Something similar occurs a bit later, when another threat is resolved sooner than anticipated, and again to deeper purpose. In this case, the heroes’ saviors are gang members—the villains of most every other inner-city thriller—a flip that underscores one of the series’ key messages: The real threat to society isn’t the traditional scapegoat but the scapegoater, the ones who created this environment.

Taking those morally simple threats off the table early allows Election Year to focus on thornier questions in its back stretch, including whether a victory over a broken system is valid if it means sacrificing the moral high ground. The film’s characters may not be the most complex of the year, but they’re defined enough—with their heroism changing with the circumstances—that this plays out in troubling, compelling shades of gray. (Also worth noting, the film creates more nuanced roles—and more roles, period—for actors of color than most mainstream releases.)

The Oscars recognize thriller screenplays more often than you might expect, although the bias is unsurprisingly toward more mainstream and prestige ones like Captain Phillips, Argo, and The Departed. (Only The Silence Of The Lambs approaches Purge levels of pulpiness, and that has a far greater sheen of respectability.) But Election Year holds nothing back and is all the more effective for it, especially given the ugly election year we just experienced. In the boldest publicity choice of the year, it marketed itself under the tag “Keep America Great.” If nothing else, that’s got to count for something.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)