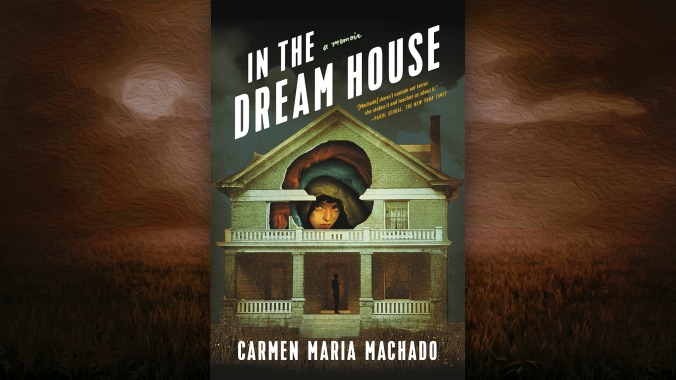

In The Dream House mixes genre to craft a powerful memoir of an abusive queer relationship

“You think, this will be a good story, one day.”

“Don’t you ever write about this. Do you fucking understand me?”

Memories can be reconstructions or re-creations but never recordings—one individual’s recollection of an event or series of events only takes into account their experience, their emotions. Like photographs, memories fade or can have a narrow field of vision. For Carmen Maria Machado, those limitations are both aids and impediments in constructing her memoir, In The Dream House.

A literary feat and catharsis for the author, In The Dream House recounts in part Machado’s years-long emotionally and psychologically abusive relationship with an unnamed woman who is referred to primarily as “your girlfriend” or “the Woman in the Dream House.” But this is no linear story of love, loss, and closure, though it is certainly concerned with that cycle. Machado, who reveals a grad school obsession with fragmentation, breaks up that arc, jumping from the past to the present and back again, from pit of despair to first blush of romance to the third or fourth reconciliation. There is a vague sense of the flow of time, but Machado often pushes setting and vocation and family to the side, leaving only one constant: the Woman in the Dream House, who demands to be all of those things for Machado while withholding so much from her.

Machado takes the splintering a step further, framing moments and traits in dozens of different narrative techniques and tropes. The story of the Dream House—which is symbolic of the relationship and its pain, pleasure, and all—is seen through the lens of the bildungsroman, the haunted house, an American gothic tale. Facets of it transport us into a lesbian pulp novel, a psychological thriller, and a queer cult classic. The chaos and the joy of those years are distilled into famous last words, an idiom, a warning, and, just as frequently, an epiphany. Machado adds a few hundred more pieces to the jigsaw puzzle of her catastrophic relationship with a list of footnotes from Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index Of Folk-Literature that are as much an inventory of through-lines as red flags. But the memoir remains as cohesive as it is foreboding, echoing the meticulously crafted dread of Machado’s 2017 short story collection, Her Body And Other Parties. We’ve all seen or read enough stories about hopes and passions projected onto buildings to know that, in real life, the dream house is rarely ever completed or found.

As the Dream House is built and torn down, Machado’s witty and resonant prose becomes a sturdier foundation than the promises made by her former partner. The shifts in time and place are so seamless that her leaps from “Cosmic Horror” to “Barn In Upstate New York” to “Shipwreck” feel almost intuitive; of course a bucolic daydream would give way to an overwhelming feeling of isolation brought on by a huge, if understandable, miscalculation. In The Dream House balances information from the wider world with a very intimate history; citations from queer theorists and writers, along with the ever-growing wall of taboos enumerated from Thompson’s folk-literature collection, tend to elucidate instead of obfuscate.

The result is an impressive, finely calibrated work of literature, one that throws open the door to a subject that’s still rarely broached, and makes the reader’s stay equally illuminating and unsettling. Machado, heartbreakingly enough, never loses her sense of playfulness amid all this dread. By the time In The Dream House takes on the form of a Choose Your Own Adventure story, it’s become an endurance test or twisted treasure hunt for the moment that will break the reader. If you wish to learn more about the “eternal liminality” of queer women, go to page 135. For a fanciful reimagining of what it feels like to be adored and subsequently abandoned, go to page 201. For a hidden message that will stop you in your tracks, go to page 174.

Early on, after a prologue in which she despairs of prologues, Machado notes that the history of the world is an incomplete one, thanks to the violent ways through which it was shaped. Even the most extensive record-keeping can come up short by design; as just one example, studies on domestic abuse have long excluded queer people, especially queer women, leaving women like Machado at a loss for what to call, let alone how to deal with, the psychological toll of an abusive relationship. Which is what makes Machado’s inventory technique so moving. By using familiar devices, she manages to tell all of these previously unheard stories in a devastatingly efficient manner. In assuming the roles of architect and archivist, Machado makes In The Dream House as much a memoir as a monument.