In the end, there was The Bible, which closed the book on an era of religious blockbusters

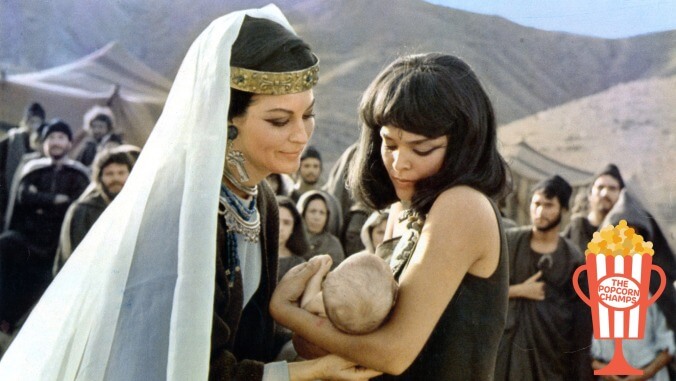

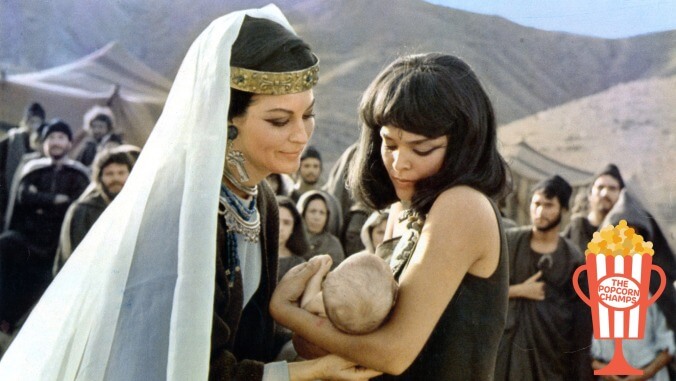

Image: Photo: Getty Images

Every director, it could be argued, likes to play god. But very few are actually willing to literally play God, to take on the Creator as an acting role. That’s what John Huston did in The Bible: In The Beginning…, his 1966 epic. Huston had to cast someone as the actual voice of God, the booming that comes down from the heavens to, for instance, cast Adam and Eve out of the Garden Of Eden. So naturally, he cast himself. Huston did, admittedly, have a great voice; 11 years after The Bible, he played Gandalf in the Rankin and Bass cartoon version of The Hobbit. But this was still a crazy thing to do, a grand and deluded and sort of beautiful ego trip.

In fact, everything about The Bible was a grand and deluded ego trip. Dino De Laurentiis, the prolific Italian producer who would later usher similarly big and weird visions like David Lynch’s Dune to the screen, had the idea to make a whole series of movies about the Old Testament. In the end, only Huston signed on, and The Bible, his story of the first 22 chapters of Genesis, went way over budget and struggled to make back its money even as the highest-grossing movie of 1966. So we never got more Bible movies. We missed out on a whole cinematic universe.

Huston wasn’t religious, and people have speculated for decades that he was an atheist, so he was a funny choice for a Biblical epic. But he was a legit film legend. By that point, he’d made The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre, and The Asphalt Jungle, among many others. He’d gone to great lengths to capture his visions, dragging Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn to Africa to make The African Queen on location, an escapade that Clint Eastwood would later dramatize in White Hunter Black Heart. And Huston had also made a valiant attempt to capture the unforgiving forces of nature on film with his 1956 adaptation of Moby Dick.

What Huston did with The Bible is a trip. He more or less treated the actual scripture as a strange, perverse series of folk tales to be filmed. Most religious epics seem to be built around the idea of a loving and embracing and virtuous God. But Huston laid out all of his stories—Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and the Ark, the Tower of Babel, Abraham’s whole saga—as absurdist myths, rendering them as alien and primitive as anything in 1984’s Conan The Barbarian, another De Laurentiis production. Writing about The Bible, Pauline Kael called it a “flashy demonic gesture” and “crazy, sinfully extravagant movie-making,” and she liked it.

The Bible is one crazy spectacle after another. An apple mutters its temptations to Eve. Faithless hordes—or at least like 20 people, anyway—gather to laugh mirthlessly at Noah as he builds his Ark on dry land. Nimrod, cackling, fires an arrow up into the heavens. The image of Peter O’Toole’s death angel flickers on the horizon. And Sodom and Gomorrah don’t look much like cities; they’re some sort of continuous orgy of teeth-baring painted people.

The best moments of The Bible are the ones that attempt to transcend the idea of film entirely. As Huston narrates the beginning—he’s the narrator and the voice of God and also Noah—we see nothing but a dark screen and floating, out-of-focus abstract shapes, at least until God decides to form the earth. And when He does, the film becomes a cosmic and experimental spectacle: sunlit clouds, rushing waters, bubbling lava. For about its first 10 minutes—the span of time before Adam finally shows up—The Bible is a wild little stoner movie, something about halfway between 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet Earth.

But then the people show up, and things get ridiculous. Adam and Eve, for instance, look like glassy-eyed hippies, blonde and blue-eyed and permanently dazed. (Adam is Michael Parks, the guy who would later play a cop in a bunch of Tarantino movies.) Richard Harris, two years before he recorded “MacArthur Park” and 35 years before he first played Professor Dumbledore, gives us Cain as bundle of crazy gesticulations, a sort of mime version of evil. The movie’s idea of a happy ending is the one where Abraham, finally called off by God, stops just short of stabbing his own son to death. As entertainment, it is rough.

The dialogue in The Bible is all ripped straight from the King James Bible, which doesn’t make things any easier. The actual Bible may or may not be the Word Of God, but it still could’ve used a script polish. To hear actual human beings chanting dense scripture back and forth at each other quickly becomes numbing. The busy score, from the Japanese avant-garde composer Toshiro Mayuzumi, is left to do much of the work of actually telling the story. And God doesn’t care about anyone’s three-act structure, either. There’s no plot to The Bible, no introduction and rising action and climax. It’s just a series of things happening.

A couple of actors manage to deliver actual performances amongst all this epicness. One is George C. Scott, who gets us through the interminable Abraham chapter by conveying a stentorian woundedness. Abraham doesn’t want to give up his young son as a blood sacrifice, but the voice in his head tells him to, so he makes up his mind to go through with it. That’s a ridiculous thing for an actor to attempt to get across, but Scott does his best.

The other actor who breaks through is Huston himself, who plays Noah as a sort of mischievous Santa Claus type. Huston wanted to get Charlie Chaplin to play Noah, which is fun to think about. But Chaplin, 77 at the time, turned him down, so Huston took the role on himself. And he seems to enjoy himself, which is more than I can say for anyone else in the movie. He looks at the animals with real reverence and love, even when one of those animals is an ostrich who’s inches away from his face and hissing at him. And since this is before CGI, you know that’s a real ostrich, really hissing at him. (Darren Aronofsky’s bizarre 2014 saga Noah gives us some idea of how this story might look in the CGI era. Still weird!)

The animal scenes in the Noah episode are just nuts. Huston and his crew wrangled a ton of creatures from a nearby zoo, loading them onto a film-set Ark that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. He’s got sheep and tigers and tortoises and birds and elephants, and sometimes he’s got a bunch of them in the same shot together. Apparently, the set itself was total chaos. (Huston, in a Time article reported from the movie’s set: “My god, how the hell did Noah do it?”) But the movie, impressively enough, captures all these animals in long and languorous shots, miraculously avoiding any images of them pissing or shitting or mauling each other.

But that particular kind of spectacle was on the way out. Biblical epics like The Ten Commandments or The Robe had done big business in the previous decade, but their days were numbered. Instead, different things were happening in film by 1966. Another of the year’s big hits was Thunderball, the fourth James Bond joint. The Bond movies, with their sex and violence and silly sophistication, were about as irreverent as movies could be, and they were ridiculously popular; they’d prove to be more of a blueprint for the blockbusters of the future than a movie like The Bible could ever be. And 1966 year brought Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, the movie that presaged the ’70s auteur era and helped end the Motion Picture Production Code. It made a lot of money. People wanted something else.

But they also wanted The Bible, which seems much stranger now in retrospect. Millions of people were willing to pay actual money to sit in a theater for three hours, to see a blonde-haired Adam wordlessly stare at a deer, or to see Abraham endlessly wandering through deserts. To me, a moviegoer born into a very different period, this is baffling. But if The Bible represented the death of one era of film, at least it found a strange and interesting way to die.

The contender: Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, like The Bible, is a rough watch, though for very different reasons. Virginia Woolf is simple and contained, but it’s also stark and harrowing—a vision of educated people spending a whole night venting all their pent-up spleen on each other and tearing each other’s lives apart, mostly verbally but also by seducing each other’s spouses in front of each other’s faces.

First-time director Mike Nichols was already famous, first for doing improv comedy with Elaine May and then for directing a bunch of successful Broadway shows. With Virginia Woolf, he took glamorous movie stars, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and he made them act like total monsters to each other. They responded by doing maybe the best work of their careers. It’s heavy but it’s spellbinding.

Next time: The long-awaited new era in film arrives with Mike Nichols’ Virginia Woolf follow-up The Graduate.