In the feminist fairy tales of 1998, the princess saves herself

“A woman’s heart is an ocean of secrets.” Titanic’s unofficial thesis receives flak to this day, as 21 years of hindsight confirm that, yeah, it’s strange and perhaps not very romantic for a 100-year-old woman to live her whole life in service of a man she knew for three days. In short, despite James Cameron’s attempts to render Rose a strong female lead, 1998 opened with a lot to be desired in terms of the female experience on screen. But although most of the highest-grossing films of the year don’t show it—the three biggest blockbusters, Armageddon, Saving Private Ryan, and Godzilla, were almost laughably, impenetrably male—challenges to that representation were emerging lower on the box office charts.

The year’s most literal reversal of the princess trope came in the form of July’s Ever After, a modest and decidedly un-magical Cinderella tale that flew under the radar for anyone not squarely within the demographic of young girls goggle-eyed for Drew Barrymore (who could forget those daisies?). Wrapped up in layers of brocade and sweeping orchestral music, it’s easy to have missed this female-forward offering among the more (literally and financially) explosive releases of the year. But Ever After earns distinction among 1998’s feminist fairy tales for its portrayal of Barrymore’s Danielle de Barbarac, a cinder girl whose political convictions are bolstered by her kindness, rather than hindered by it. The receding echos of mid-’90s girl power is present in Danielle’s quiet strength, which she applies (almost reflexively) to convince an intellectually smitten Prince Henry to release imprisoned slaves, fund a national university, grant equal rights to Roma people, and dispense only the most rehabilitative justice to her cruel stepmother. As Entertainment Weekly put it, Danielle is “an active, 1990s-style heroine—she argues about economic theory and civil rights with her royal suitor—rather than a passive, exploited hearth sweeper who warbles ‘A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes.’”

That screenwriter Susannah Grant penned Ever After between 1995’s Pocahontas and 2000’s Erin Brockovich suggests a growing restlessness to position female protagonists as fighters, and Barrymore still declares Danielle to be her favorite role ever, finding incredible value in a Cinderella who “rescues herself” (this version had no fairy godmother or singing mice to speak of). As she put it in a 2016 interview, “We want the prince, but if you get yourself up to that mountain instead of him carrying you up there, it’s just that kiss is all the sweeter.” Barrymore says that learning what she loved about Danielle, particularly the balance between sisterhood and romance, informed her vision for 2000’s Charlie’s Angels reboot, the sophomore effort from Barrymore’s Flower Films production company. That franchise might tread a bizarre middle ground between feminist and objectifying, but it was Barrymore’s conscious decision to do so; empowerment is, in Hollywood as with everywhere else, a Sisyphean undertaking.

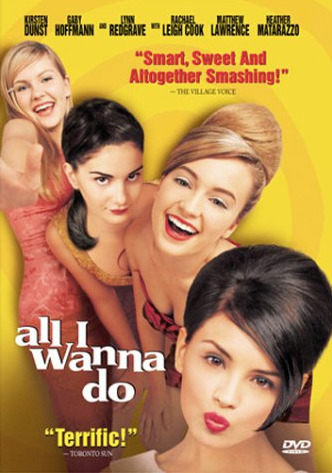

And if you weren’t privy to Ever After in 1998, there was little chance that you saw another of the year’s delightful debuts, one so modest that it was released under three different titles. All I Wanna Do (marketed as Strike! in the U.K. and Canada and The Hairy Bird in Australia) kept a bafflingly low profile that September, despite the hot careers of its stars Kirsten Dunst, Rachael Leigh Cook, Gaby Hoffman, and Matthew Lawrence. Maybe the studios had little faith that a movie about a 1960s all-girls boarding school could draw an audience, or maybe they just didn’t know how to market a movie where teen girls have authentically vicious arguments while yelling things like, “That was really uncalled for, vagina!” It’s a film with the courage to show women in their element, whether that’s as simple as going without makeup or as complicated as struggling to support a bulimic friend.

It’s not out of bounds to call All I Wanna Do its own feminist “fairy tale,” if only because, in the strictest sense, it has the elements of its more classic counterparts. Finishing school transplant Odette Sinclair (Hoffman) writes a series of lamenting letters to her boyfriend, Dennis (Lawrence), an expository tool that reads just like any Disney princess’ “I Want” song. And the supporting cast has a whole spectrum of sidekicks and frenemies who unite to topple the true villains of the film, like the sexually exploitative professor whose unpunished behavior was as typical in 1963 as it is in the modern landscape that birthed #MeToo.

Dunst and Hoffman carry the film with aplomb, two strong women bitterly divided on the matter of whether to sabotage their school’s upcoming merger with the all-boys academy. (Rachael Leigh Cook’s heel face-turn as goody two-shoes Abigail Sawyer is also an award-worthy performance in this strong ensemble cast.) This offbeat showcase of contemporary female talent feels as fresh in 2018 as it did in 1998 thanks to its unsanctimonious feminism, an ethos that is shown rather than told. “I’m not going to live in the shadow of the hairy bird!” Dunst’s Verena von Stefan screams at her boy-crazy friends, and while the men in this film run the gamut of “decent enough” to “indisputable monster,” it’s clear that they, unlike the women, have the choice to be whichever one they prefer. Even in 2018, the girls’ 1960s-era refrain of “No more little white gloves!” sounds an awful lot like enough is damn well enough already.

Even Disney, that traditional standard-bearer (and relentless marketer) of classic femininity, made a seemingly earnest effort to break free of its own patterns in 1998’s Mulan, its depiction of the traditional Chinese Hua Mulan ballad. Although its ratio of white voice actors to Chinese talent left something to be desired, rewrites were undertaken to convey that Mulan entered battle to preserve her family’s honor and save her father’s life, rather than the initial concept of her being betrothed to Captain Li Shang. Sidelining romance in favor of character development and female heroism—and abandoning any kiss moment altogether—showed genuine growth for Disney, even if it took pains to celebrate its own progressiveness while doing so.

It’s not an atypical year in Hollywood that pushes female-driven stories to the margins, and the same was true for 1998. But a few key offerings that year were like assurances to audiences of young girls and women that they were, in fact, seen. These films provide directives for how to live your best—and even get the guy, if that’s something you want: Be political and uncompromising. Lie your way past bureaucratic barriers. Walk away from any man dismissing your politics in an attempt to invalidate you, your billowing 16th-century ballgown trailing in your wake. If your boyfriend is a dud, break the hell up with him and move on to the next act, where the company is undoubtedly better. In 1998’s feminist fairy tales, your convictions will take you—and your narrative—further than even the liveliest choir of mice.