Intelligent, sensitive, literate, subtle: These are some of the qualities frequently ascribed to the French writer-director André Téchiné, for all the good it’s done him in terms of earning an American following. Even though he’s been winning awards and working with stars (Juliette Binoche, Daniel Auteil) since the ’70s, Téchiné hasn’t become a brand name like some of the other French filmmakers of his vintage (including his former screenwriter Olivier Assayas). Even a film like Wild Reeds—a marvelous coming-of-age fable that swept the New York and Los Angeles film critic awards back in 1994—has slipped through the cracks of the contemporary canon. In an era in which art-house directors from Paris to Seoul have embraced extremities of form and content, Téchiné’s smooth, proficient ensemble dramas seem to reek suspiciously of respectability.

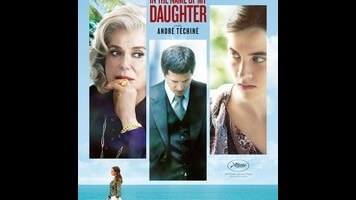

This is definitely the case with In The Name Of My Daughter, which premiered out of competition last year at Cannes and was met by skepticism by major trade publications, whose critics carped that Téchiné had siphoned the excitement out of a real-life story about Mafia power struggles on the French Riviera in the ’70s. It’s true that the film, which stars Catherine Deneuve as a casino owner undermined financially by her daughter before the latter disappears under mysterious circumstances, is conspicuously bloodless. But that shouldn’t be taken as evidence of a failed artistic choice. Téchiné, whose recent The Girl On The Train was also a fact-based melodrama, is underplaying his tale of manipulation and betrayal to indicate the ways that gentility and prosperity so often gild the lily of human cruelty.

The three protagonists here are all flawed. Deneuve’s old-monied matriarch Renée Le Roux sees herself and her cavernous, well-worn establishment as bulwarks against the nouveau riche gangsters trying to remake Nice into a neon hellscape, but she’s more interested in preserving her finances than any sort of local tradition. Her daughter Agnès (Adele Haenel) is a fresh-faced world-traveler whose indifference to the family business makes her—and her rather large monetary stake—a flight risk, especially once she enters the orbit of Renée’s reptilian business advisor Maurice Angnelet (Guilliame Canet), a serial womanizer who sees the generational schism and senses an opportunity. Agnès’ narcissistic self-regard belies her romantic inexperience, and Maurice seizes full advantage, taking the younger woman as his lover while subtly turning her against her mother, who sees what’s happening and is helpless to stop it.

In The Name Of My Daughter is a film with a thesis, which involves the fate of Agnès LeRoux—featuring events that Téchiné pointedly leaves off-screen. He’s less interested in speculating on the shape of any possible foul play than creating a dramatic context for that kind of violence. And on that count, he succeeds splendidly: There’s a lurking sense of unease here made all the more acute by the ways the characters keep trying to tamp it down. Deneuve, who has acted for Téchiné many times, is excellent in a role that takes full advantage of her grand-dame iconic qualities, while Haenel is terrific as a privileged kid in over her head. Her absence is felt in the epilogue, which picks up decades after the main action and takes the form of a conventional courtroom drama—albeit one where the legal outcome is secondary to our own judgments about the case. Like any good prosecutor, Téchiné gives us enough information to render a verdict without bullying us into agreement. His gift to his viewers is the space to think for ourselves.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.