In the season finale, his name is Berkman. Barry Berkman.

“Telling the truth is the right thing to do, right?”

In “berkman > block,” three characters come to the edge of an honest, epiphanic moment…and then slowly back away from it. There’s no one reason for their decisions, but rather a mixture of fear, clouded judgment, and myopia. Everyone in Barry fights to live honestly, to atone for their regrets, however minor or major they be, and move forward with a healthier, principled worldview. But every time they get close, they sabotage their own efforts. Epiphanies aren’t enough. Ultimately, follow through is required.

A stellar finale written by Alec Berg and Bill Hader, “berkman > block” caps off a great season of television by masterfully tying off every loose end, even ones that were tossed off or buried, and seamlessly connecting the series’ two worlds, thematically and narratively. What’s most impressive is that it never once feels tidy or closed off. On the contrary, the airtight writing only amplifies the emotional messiness, illustrating how the characters’ actions can’t be reduced to psychologically pat explanations. People are driven by many conflicting passions, by both positive and negative behavior, by an overwhelming self-awareness and an irrepressible impulse. Berg and Hader go to great lengths to capture the internal contradictions and their unfortunate outcomes.

It might be best to start with Sally, a person who sees herself as an artist but has never really received an opportunity to prove herself. But with Lindsay’s sold-out showcase, she finally finds the perfect venue to introduce, and expose, herself to the world. (It also certainly helps that her story is easily the best in the class and the rest of her peers will only make her look better by comparison.) At the same time, the cracks begin to show early on. She nervously smokes a cigarette as Barry arrives to the 400-seat auditorium. She putters around the space with her script, barking orders and making notes. Her confidence frays even further when she sees that Lindsay, her sincere professional advocate, is also a nervous wreck. There’s a lot riding on this scene and Sally feels every inch of it, so much that she barely registers that Barry is similarly falling apart for an entirely different, graver reason.

All the pieces are in place when Barry and Sally finally step on stage. But Sally chokes at the very last possible second. On second thought, it might have been better if she choked in the traditional sense. Instead, she throws the table aside and performs the wish-fulfillment version of the scene where she tells off Sam. Sarah Goldberg plays that moment expertly, leaning into the “screaming = good” bad-actor cliché. It’s a comfortable place for Sally, but it’s ultimately a false one that serves to self-flatter and obscure the truth, embodied by the most hackneyed exit line imaginable: “My name is Sally Jane Reed and as of today we are fucking done, you son of a bitch!”

Devastated and ashamed, Sally tries to sneak away from the showcase. Lindsay catches her and wants to take the blame for pushing her to perform such a vulnerable piece in this type of setting. Except the best and worst outcome happens: Everyone loves it. The Michael’s commend her on the hopeful, inspiring version of a story in which a woman takes charge of her life. Other patrons surround her to praise her bravery. She and Lindsay exchange embarrassed looks as the crowd swells. This might in fact be her meal ticket, the showcase that leads to the next thing that leads to the even bigger thing that puts her on the map. And it’s based on a lie.

Meanwhile, Fuches flees the woods to the monastery to assist Hank with operations and seek protection from Barry, who’s on the warpath. The problem is that Hank, following his embarrassing lack of leadership when the Burmese were about to kill them all, no longer has control over his men, and will soon be shipped back to Chechnya as punishment. Just as the Burmese and the Bolivians arrive to begin an all-out assault on the monastery, Fuches sees an opportunity to prove his worth. He walks outside to address Cristobal openly about Hank’s betrayal to prevent the siege that’s about to take place.

“You and Hank, you’re in a transitional phase. That’s all! People meet and sometimes they lock into each other, like two long-sought-after pieces of a puzzle. Now, as time goes on, these pieces, they morph and they grow, and they can grow together and become stronger, or they can become two completely different shapes that…they don’t have any room for each other, they don’t fit anymore. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my life, you can’t control what other people are gonna do. No. They need their own space to become whatever weird-ass shape they’re going to change into. It’s nature. You can’t control it, but you can accept it. And I think, you know, you and Hank, that’s still a fit, man.”

While the irony of Fuches’ speech might be too obvious on paper, Stephen Root sells it by never entirely tipping whether Fuches comprehends the subtext. There’s a brief, split-second glimmer in Root’s eye where it seems like Fuches realizes that he’s actually talking about him and Barry, but he pulls it back because, at the end of the day, this is still manufactured bullshit concocted to ensure he’s in the Chechens’ good graces. Given that Fuches is a master manipulator, it works. It’s worth noting here that Berg and Hader impressively never hang a lampshade on Barry’s other major irony: that the various criminal gang members are living the most honest lives in the series. All of Hank’s feelings exist on the surface. He can’t hide them if he tried. It’s why Hank and Cristobal’s reconnection stands as an oddly earnest emotional moment, even though it centers upon mafia leaders geeking out over their heroin shipment.

If Fuches really believed that people need their space to become their own weird-ass shape, then he would have walked away from Barry after they escaped from the Ronny Proxin situation. Instead, he follows his pettiness to the end of the line and threatens to ruin Barry’s life by destroying Gene’s. The LAPD land at the scene just when Barry arrives at the car. Detective May spearheads the investigation and quickly concludes that Gene murdered Moss, bolstered by a voicemail confession left by Fuches. Gene, deep in shock, doesn’t register any of this. Barry, completely conscious and wracked with guilt, registers all of it.

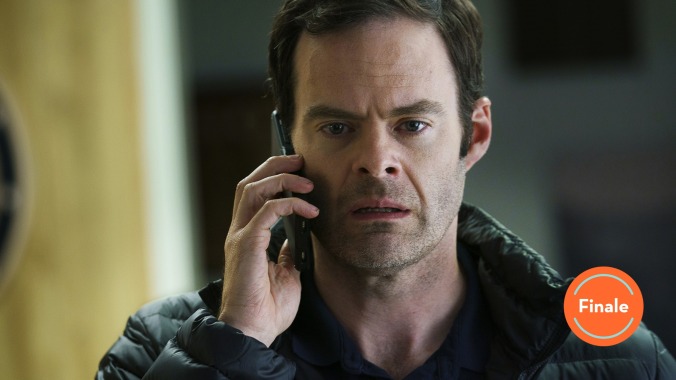

Hader does more with less in this episode, subduing all of the wrath and hurt he feels by keeping it an inch below the surface. He threatens to kill Fuches on the phone, but he delivers it through tears. He can barely pay attention to Sally as she freaks out before the performance. When she slaps him in the face so that he can “remain present,” there’s a moment where it really looks like Barry plans to take out his anger towards Fuches on his girlfriend in front of an audience. Strangely enough, it might have been helpful, if only because it would have given an outlet to those emotions. Instead, he just stews in the guilt and the shame and the rage.

It’s important to remember that the blame for all of this still lies at Barry’s feet. If he had chosen to own up to his crimes, he wouldn’t have needed to murder Moss. He still might have received blowback for killing the Chechen leadership, but his crimes wouldn’t have been in his personal backyard. Fuches might be an asshole, but his needling comes with a harsh truth: Barry could easily take the fall for Moss and save Gene’s life, but he’s just not that altruistic. So, he finds a work-around by placing Hank’s Chechen pin that says, “The debt has been paid” into the trunk, which convinces the LAPD that Moss’ murder was gangland retaliation. Gene is free to go.

“Can you tell your dad something for me?” Barry tells Gene’s son Leo on the phone. “Can you tell him that he’s going to be okay? And that he was right. I’m pretty sure that people can change.” It’s a pretty rich statement coming from the guy who just planted false evidence in order to save himself and his mentor, and yet it’s possible to see the shaky, but truthful foundation. Barry worries that he’s an evil, violent guy, and has desperately sought to put those feelings behind him. Maybe that act of self-preservation can be construed as a last-ditch effort for him to stay on the right track. Maybe he needs to live with and maintain that one last lie so that he can move forward. Everyone deserves a second lease on life, right?

Then Barry receives the text from Hank tipping him to Fuches’ location and everything goes to hell.

The violence in Barry has never once felt fantastical. Even in “ronny/lily,” where it’s heightened to a comical degree, it feels remarkably real. When people bleed, there’s awareness that a body only has a finite amount of blood. Pain feels immediate and excruciating. Suffice it to say that Barry’s mass murder spree is downright disturbing. It’s the unhinged actions of a man hell-bent on vengeance against an elder who showed love purely for selfish ends. But in the end, he doesn’t get Fuches, who sneaks out the back. All he does is murder an entire swath of Chechens, Bolivians, and Burmese. At one point, a man chokes on his own blood before collapsing to the ground. Later, we see two men cowering in a room accompanied by a third man with a gun. None of them speak English. Barry kills them all anyway. Hader plays up the vulnerable or goofy sides of his character so often that it’s sometimes easy to forget that Barry is a violent assassin, and that, as Fuches says, ending a life takes someone with no soul.

In the end, it’s Mayrbek’s lifeless body that gets through to Barry. During their training sessions, Barry tells him that if he loses his focus, if he gives the other guy a chance to fire, then he’s dead. Sure enough, the scene plays out here. Mayrbek had the drop on Barry, but he paused just a moment. Why? Because Barry gave him confidence and purpose. He showed him how to be a leader, how not to be afraid. That moment of empathy caused him to think for a second about his actions. But Barry didn’t pause. He delivered a bullet to his brain without a second’s thought. And in the end, that’s the kind of person he is. People can change. Barry, on the other hand, might not be able to.

As Barry walks straight into the darkness, Gene Cousineau lays up at home fondly remembering the love of his life. Their first dinner. Their first night together. Cooking. Laughing. Then the trunk. Then Fuches whispering something in his ear. What was it? What could it be?

Berkman. His name is Barry Berkman. Oh my God indeed.

Stray observations

- Besides Hader, Anthony Carrigan is the true MVP for the season, and his performance would net industry and awards recognition in an ideal world. Just about every line he delivers in this episode is hilarious, but him on the phone with the furniture store trying to buy a “heroin table” is a series high point: “What I’m dealing with is an open-floor plan, so it really needs to work on its own merit.”

- There’s so much sexual energy between Hank and Cristobal that even Fuches notices it. “Jesus Christ, easy, easy, you guys are like my cats, I have to pour water on ya.”

- Sasha committing to her horse story at the showcase and then stumbling upon her trauma, which she clearly repressed, is such a perfect gag to toss off: “This is walking down this and was seen by her. Not actually her, this is not a photo of me, I don’t have any photos of me from my childhood because my uncle burned down my house while my mum was still inside, but that…that is not relevant to this story, is it?”

- Michael deflating hemorrhoid pillow while praising Sally’s speech is such an amazing character touch.

- “Lindsay sold out the place. She told people it was a diversity showcase and I think they were afraid not to RSVP.”

- “Oh, come on. You guys are like Fleetwood Mac. You break up, you get back together again, and then you go out and make a great album, like The Best of Fleetwood Mac.”

- That’s it for season two coverage of Barry! As always, thanks to those who read and followed along. We’ll see what happens next year when Berg and Hader will attempt to write themselves out of yet another seemingly impossible corner. They did it once, so let’s hope they can do it again.