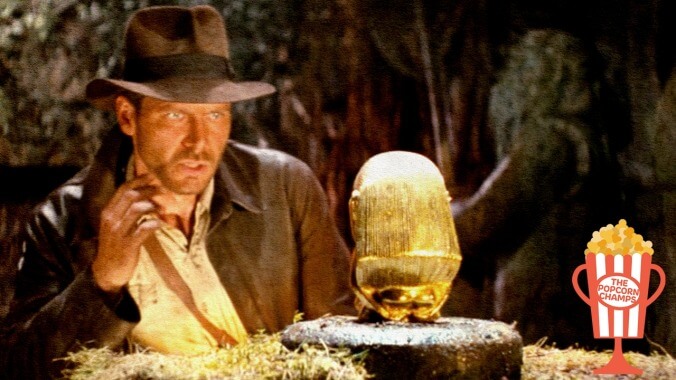

Indiana Jones made his Nazi-punching debut in the ultimate Disneyland ride of a movie

Image: Graphic: Natalie PeeplesScreenshot: Lucasfilm Ltd.

The plane has just exploded. Indiana Jones and Marion Ravenwood have killed about a dozen Nazi soldiers and escaped. Against all possible odds, they have survived. They could return to their lives. But they won’t do that, since the Nazis are still in possession of the Ark of the Covenant. Indiana Jones can’t let them keep it. Leaning up against a sand dune, barely catching his breath, Indy tells his friend Sallah, “I’m going after that truck.” Sallah is confused. “How?” he asks. This is a reasonable question. Indy seems annoyed at having to even consider it. “I don’t know,” he says. “I’m making this up as I go.” One second later, Indiana Jones bursts out of a tent, riding a stolen horse, ready to embark on one of the greatest chase scenes in film history. That’s all the setup he needed.

Steven Spielberg wanted to make a James Bond movie. That’s what he told George Lucas when the two were on a Hawaiian vacation together with their wives in 1977. Star Wars had just come out, and Lucas was learning of its massive, world-altering success through news reports. Spielberg was taking a break from making Close Encounters Of The Third Kind. The two young directors who’d just conquered Hollywood were thinking about what they wanted to do next. Spielberg was thinking Bond. Lucas had another pitch.

A few years earlier, Lucas had the idea to write a film inspired by the old ’30s adventure serials he’d enjoyed as a kid. He’d spent some time writing a script for The Adventures Of Indiana Smith with the director Philip Kaufman. But Kaufman had put the project on hold to make The Outlaw Josey Wales with Clint Eastwood. (Eastwood later fired Kaufman from Josey and finished it himself.) On that vacation, Lucas sold Spielberg on the idea of this rugged-archaeologist romp—the sort of purely fun childlike film spectacle to which Spielberg and Lucas were both drawn. A year later, the two sat down with Lawrence Kasdan, a young screenwriter who still hadn’t written anything that had actually been made, to figure out the story.

“What we’re doing here, really, is designing a ride at Disneyland,” Spielberg kept telling his collaborators. Spielberg wanted Raiders to be less of a linear story and more of a series of increasingly giddy cliffhangers. Spielberg, Lucas, and Kasdan designed Indiana Jones to be a classical, mythic man of action, the kind of guy who steals the horse and launches himself after the truck without thinking twice about it. They succeeded wildly. Raving about Raiders, Roger Ebert wrote, “It’s actually more than a movie; it’s a catalog of adventure.”

Most critics felt the same as Ebert: Raiders was a dazzlingly fun technical marvel that worked as a thrill ride. For the few critics who hated the film—Pauline Kael in The New Yorker, Stanley Kauffmann in The New Republic—that was the problem. With its endless forward momentum and its total lack of three-dimensional human characters, Raiders, to these critics, was a marathon of exhausting spectacle. That line of thinking is familiar now—a few months after Lucas’ and Spielberg’s contemporary Martin Scorsese raised hackles by saying that Marvel movies are closer to amusement park rides than cinema. And yet what’s remarkable about Raiders is that, 39 years later, it holds up as one of the most purely entertaining cinematic experiences ever concocted. Maybe it’s a Disneyland ride. But it’s the best Disneyland ride. (It’s also an actual Disneyland ride, and it has been ever since the park opened up The Indiana Jones Adventure, in 1995.)

When Spielberg sat down with Lucas and Kasdan to write the movie, they thought of the action scenes first, and then they figured out how to string them together. (When they didn’t have room for one of the set pieces they thought up, they used it in one of the sequels; it’s how we got the shootout in the Shanghai bar from Temple Of Doom.) Those scenes are so good—so energetically staged, so magnificently filmed, so well-acted—that nobody really bothers to complain about plot holes or logical fallacies. For most of us, skepticism is no match for the image of Harrison Ford running away from that big fucking boulder.

Like Star Wars before it, Raiders is pure film-nerd pastiche. Lucas and Spielberg weren’t concerned with capturing the messy sprawl of actual human emotion. They were drawing on old movies, as well as memories of kid-culture staples like pulp novels and Uncle Scrooge comics. Raiders is full of visual quotes, and Spielberg went so far as to dress Indiana Jones like Charlton Heston in 1954’s Secret Of The Incas. Spielberg and Lucas weren’t exactly inventing. They were drawing on American myth, on the collective unconscious.

That’s not a complaint. Raiders just works. The storytelling is drunk on its own self-conscious silliness. Spielberg’s rhythm is virtuosic—the way the edits hit the beats of the blaring John Williams music, the way every nasty moment has a comic reaction shot that lets the audience know it’s okay. In my action-movie history column a few years ago, I wrote about Raiders as a classic of the genre. And it is that, but the fights have an almost dreamlike sense of unreality—a Douglas Fairbanks theatrical swashbuckling quality, combined with a screwball-farce looniness.

If you look hard enough, you can find some sense of profundity in all this spectacle. Belloq, the villainous French Nazi collaborator, tells Indiana Jones that the Ark is “a radio for speaking to God.” When Spielberg has his characters speak of his MacGuffin in such hushed tones, and when he films it emitting rumbling ambient hums, he turns it into a vector, a vehicle for awe. For Spielberg, the Ark—like the UFOs in Close Encounters Of The Third Kind and maybe like the shark in Jaws—is a way of communing with the uncanny, of coming face-to-face with ancient forces that humans can’t understand.

You could also argue that Raiders is the first knowingly Jewish movie that Spielberg ever made. The Nazis, in their search to destroy Jewish civilization, attempt to possess its greatest piece of antiquity. None of the characters are actually Jewish. Before he opens the Ark, though, Belloq dresses as a rabbi and recites a Torah prayer. Belloq soon learns that God is not on his side. In its own way, the horrific EC Comics vision of God’s vengeance at the end of Raiders—the flesh melting from the faces of Nazis and collaborators—is as cathartic as watching Hitler get blown to bits at the end of Inglourious Basterds. Years before Spielberg was ready to seriously take on the Holocaust, he was getting his comic book revenge on the Nazis.

And yet Indiana Jones himself isn’t some soldier of God. He’s out for glory and notoriety. He makes moral decisions, like when his respect for history won’t allow him to destroy the Ark with a bazooka. But mostly, he’s a grumpy, laconic, wisecracking plunderer who finds himself fighting on the side of good almost by happenstance. He is, in other words, a whole lot like Han Solo. For that matter, Indiana Jones also falls for a tough and sarcastic big-eyed brunette woman who’s a lot younger than him but who still knows how to handle herself in a fight. (Karen Allen, cast after kicking ass in Animal House, is so good at all of this.) So it’s remarkable that Harrison Ford, who filmed Raiders in between Star Wars movies, was able to make Indiana Jones so distinct from his other iconic character.

Like many truly successful movies, Raiders is a series of happy accidents. Even with Lucas and Spielberg on board, it wasn’t a sure thing. Spielberg was coming off of 1941, his first real flop. After breaking out in Star Wars, Ford had headlined failures like Hanover Street and The Frisco Kid. Ford almost wasn’t even cast; he only got the job when Tom Selleck couldn’t get time off from shooting Magnum P.I. It’s Hollywood lore that every studio turned down Raiders before Paramount took a flyer on it, making it for the surprisingly low budget of $18 million. The film earned $212 million.

Raiders didn’t just become a cultural phenomenon because it was a great movie, though that didn’t hurt. Raiders also had good timing. For one thing, it took the dizzy kids’ adventure sensibility of Star Wars and made it earthbound, adding in enough violence that it seemed more adult. And Raiders also presented the image of an American who could swagger his way through the rest of the world and end up victorious. After the years that America had just been through—the humiliations of Vietnam and Watergate and the Iran hostage crisis—that must’ve been a reassuring sight.

Raiders also had the romance of nostalgia working for it. The 1936 of Raiders was a violent and perilous place, a place where even a monkey would turn on you and sell you out. Spielberg still depicts it as a fun place to be—a place where Americans haven’t yet shown their ass on the world stage. In The New Republic, Stanley Kauffmann called the film “an eloquent testimony of faith in pastness.”

In 1981, faith in pastness was strong. Less than a year before the release of Raiders, that faith in pastness had led America to elect Ronald Reagan—a man who, in his previous life as a movie star, had made proto-Raiders adventures like 1952’s Hong Kong. Reagan presented himself as an avatar of old-timey American machismo. Spielberg and Lucas presented Indiana Jones in much the same way. Whether or not they meant to do it, they tapped into a national mood.

Nostalgia was a big deal at the 1981 box office. Raiders wasn’t the only old-school comic adventure to do business that year; Superman II, The Cannonball Run, and For Your Eyes Only (the Bond flick that Spielberg would’ve made?) were all among the year’s biggest hits. The year’s box office runner-up traded on a different kind of nostalgia. On Golden Pond gave audiences one last chance to bask in the glamour of Henry Fonda and Katharine Hepburn, stars of the Reagan generation. Raiders and On Golden Pond aren’t terribly similar movies, but they both make for comforting spectacle.

Even if Raiders owed some of its success to a reactionary idea of America as it once was, it stands on its own as an all-time achievement: the amusement park ride transformed into pure cinema. Years later, it seems absurd that Raiders lost Best Picture to a more obvious prestige-grab like Chariots Of Fire. But Spielberg would end up winning anyway. In the years ahead, he would tighten his stranglehold over the entire idea of comforting spectacle, turning his version of childlike wonder into the lingua franca of American cinema. He did this without any sort of overarching master plan. He made it up as he went along.

The runner-up: Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits is a surreal and anarchic and frequently nasty piece of wonderful nonsense that somehow ended 1981 as the year’s #10 earner. In some ways, Time Bandits is a special-effects adventure story not too tonally distant from Raiders Of The Lost Ark, or from the movies that inspired it. (Original James Bond Sean Connery shows up to twinkle his eyes in a couple of scenes.) But Gilliam and his old Monty Python cronies also find room for acid satire and dream-logic absurdism, as well as the brain-searing heightened visuals that would become Gilliam’s trademark. It’s amazing that a movie this weird had a chance to succeed, that it was allowed to baffle and amaze millions of kids like me.

Next time: Steven Spielberg goes back-to-back, making the world fall in love with the rubber puppet at the center of E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.