Inferno tries to find the fun in a Dan Brown thriller

Although they’re written like garbage, Dan Brown’s Langdon novels have always seemed like they would make fun movies: National Treasure meets Foucault’s Pendulum in an old point-and-click game. They’re all about Robert Langdon, a famous Harvard professor of symbology, which is a field Brown made up; you can tell because “symbology” and “symbologist” sound like mush in a spoken English sentence. In the Brownverse, where he is the smartest man alive, Langdon solves mysteries that involve the Catholic church, the Freemasons, the Illuminati, and the World Health Organization. These are often uncovered in Italy, always with the help of museums and usually within a day. The books themselves are riddled with errors in history, geography, science, and grammar. Brown appears to have no editor, which doesn’t bother the majority of his millions of readers, and is the main point of attraction for the minority who read his books out of sick pleasure.

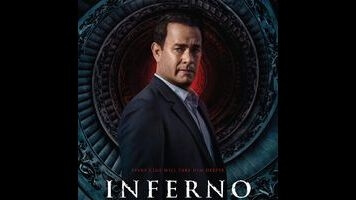

To date, three of Brown’s Langdon novels have been made into movies: The Da Vinci Code, Angels & Demons, and now Inferno, all directed by Ron Howard, with Tom Hanks in the role of Langdon. This latest film, which was made on about half the budget of either of its predecessors, is as close as the Langdon-Howard cycle has gotten to actually being fun. Brown’s stories are defined by their almost surreal fuddiness, a mix of conspiracy-nut mumbo jumbo and banality that is more or less encapsulated by the idea of something called “Ron Howard’s Inferno.” A viewer’s ability to enjoy a movie like this is roughly triangulated by the following points: the fact that the “Inferno virus,” a MacGuffin-ish apocalyptic plague, is kept in fluid in a small plastic bag, like a goldfish; the look of joy that Langdon gives when he is returned his prized Mickey Mouse wristwatch at the end of the film, having already saved the world; and the irritation with which all of the characters go about unmasking or perpetrating a conspiracy, defined by the way Harry Sims (Irrfan Khan), the blasé, scene-stealing master of a mercenary syndicate, carries medical gloves in the pocket of his wool three-piece suit in case he needs to stab someone.

Inferno is the first movie to grasp the Ed Wood-ian quality of Brown’s writing. On a technical level, he’s one of the most amateurish writers to ever earn a massive global readership. Periodically, his prose blunders into the indelible, producing the likes of “But the man’s head was misshapen… badly,” “We are on the brink of the end of humanity,” and “Elizabeth Sinskey stood at the bottom of the cistern stairwell and gazed at the void of the evacuated cavern.” (All from the novel Inferno, by the way). The film adaptation, written by David Koepp (Jurassic Park, Spider-Man, Carlito’s Way, and so much more), is the first Hollywood blockbuster in which the word “chthonic” is said out loud. Its screenplay omits some of the more memorable oddities of the source material, including a major character’s stress-induced alopecia and an ending in which Brown appeared to come out in support of forced sterilization. But it does grant its own moment of strange poetry by having Langdon muse to himself, in a cadence specific to Hanks, ‘The most interesting things happen in doorways.”

There is another moment, later in the film, that hits just the right proportion of the overwrought, the mundane, and the clichéd: a bombing briefly foiled by the bomber’s inability to catch a signal for the cellphone detonator. Almost ingeniously dumb, it hints at the movie Inferno could have been.

This time around, Langdon finds himself in a hospital in Florence without his watch and with no memory of the last 48 hours; at first, he thinks he’s still in Cambridge. After an apparent assassination attempt by a stern-faced gunwoman in a Carabinieri uniform, Langdon escapes into the city with the help of the attending physician, Dr. Sienna Brooks (Felicity Jones), a former child prodigy with a convenient love of puzzles. Together they begin deciphering clues that point to a conspiracy themed around Dante’s Divine Comedy—something about a virus designed to wipe out half of humanity in order to reduce the world’s supposedly burgeoning population and trigger a new Renaissance. Despite Langdon’s agonizing investigative methods, which involve reading things out loud very slowly and running into museums to shout factually inaccurate information about historical figures, said conspiracy is thwarted before the day’s end.

Figuring in all of this are Sinskey (Sidse Babett Knudsen), a WHO director who is also Langdon’s ex-girlfriend; her lackey, Bouchard (Omar Sy); Betrand Zobrist (Ben Foster, seen mostly in videos and flashbacks), a Peter Thiel-esque billionaire elitist who commits suicide by tumbling out a belfry in the opening scene; and Sims’ shadowy organization. A shorter and brisker movie than either The Da Vinci Code or Angels & Demons, Inferno also benefits from the fact that its director has become a little bolder since he last adapted a Brown novel. Howard is still one of Hollywood’s go-to middlebrow craftsmen (which isn’t necessarily a knock), but his recent collaborations with cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle on Rush and In The Heart Of The Sea revealed that he might have just a little of an artist in him, too.

Returning to the touristy Italian locales and museums of the earlier Langdon movies with the same cinematographer, Salvatore Totino, Howard isn’t as slickly professional as before. Here and there, he’ll drop in an angle that’s just offbeat enough to play to the pulpiness of the plot—a point-of-view shot of running feet in the opening chase scene, for example. The change in tone isn’t radical, but it’s still pervasive; while Hans Zimmer scored Howard’s previous Brown adaptations with generic strings, here he goes for faux-vintage synths that occasionally sound like James Horner’s score for Commando, minus the steel drums. But Inferno only partially embraces the elements of its source material that have the potential to be juicy or interesting: Langdon’s apparent dickishness, the strange naïveté of the characters, the combination of picturesque plazas and gruesome deaths by falling. (There are several.) As such, it’s still only partway to a Robert Langdon mystery that fully qualifies as entertainment.