Intolerance gets Purged in Assassination Nation, a midnight movie more righteous than exciting

In the tradition of William Castle, who enticed audiences with ostensible danger—taking out an actual life insurance policy on those who saw a particular screening of Macabre (1958); including a countdown to the scariest scene in Homicidal (1961), so that viewers had time to flee the theater—Assassination Nation kicks off with a series of tongue-in-cheek “trigger warnings.” Accompanied by split-second glimpses of gruesome imagery from later in the film, on-screen text warns the wary of such impending horrors as blood, gore, torture, murder… as well as toxic masculinity, sexism, transphobia, fragile male egos, and the male gaze. This is very much a midnight movie of our current moment, positioning itself as transgressive and dangerous while simultaneously reassuring us that it’s on the right side of various hot-button issues. That’s a tricky tightrope to walk, and writer-director Sam Levinson prioritizes righteousness over true mayhem.

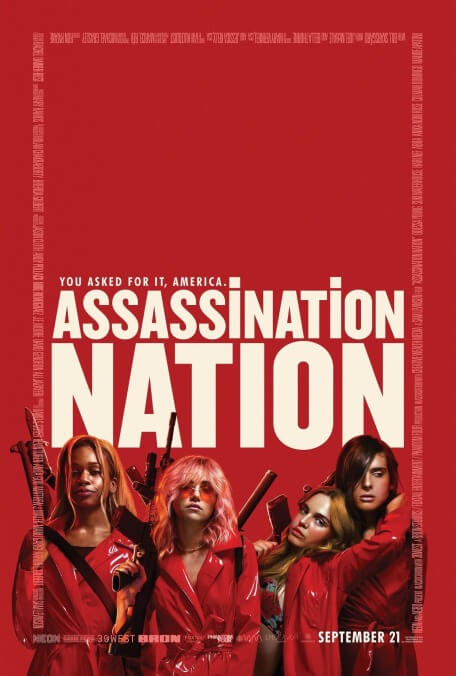

The experience can certainly be cathartic, though. Rather than a “final girl,” Assassination Nation offers a tight-knit quartet: best friends Lily (Odessa Young), Sarah (Suki Waterhouse), Bex (Hari Nef), and Em (Abra), who attend high school in a town pointedly called Salem. Each has her own daily struggles to contend with. Lily is secretly semi-involved with the older married man (Joel McHale) whose daughter she used to babysit, for example, while Bex, who’s trans, gets ghosted by a jock unwilling to be seen with her in public. But things really get hairy once a mysterious hacker starts posting the contents of people’s smartphones on the internet. Suddenly, everyone’s vices are public knowledge, and Salem transforms overnight into an ultraviolent cesspool of slut-shaming, retaliation, and just outright hatred of the other. What’s more, the local computer nerd claims to have discovered that all of the hacks originated from Lily’s IP address, sending the entire town (including cops) on a murderous vendetta in her direction.

South Park recently devoted most of an unprecedented season-long arc to this basic idea: What would happen to society if everyone had access to their friends’ and neighbors’ emails, texts, and browser histories? Assassination Nation channels the conceit into horror rather than comedy (though certain aspects qualify as black comedy), but Levinson’s choice to up the ante by having half of Salem get hacked transforms what starts out as a Heathers-style satire into just another variation on the Purge franchise, with our heroes threatened by mask-wearing vigilantes wielding guns and knives. Nor does the film really grapple with the potentially discomfiting notion that all of us, however outwardly respectable or conformist, have something to hide. Instead, it slowly transforms Lily, Sarah, Bex, and Em into martyr-warriors pitted against the collective forces of intolerance and belittlement. They’re fun avengers to cheer for, but drawing such a starkly defined moral line inevitably dilutes any feeling of real danger. Assassination Nation tells you right up front what to be appalled by, then simply delivers what it promised. Unlike the best examples of either horror or satire, it ultimately comforts and confirms rather than challenges.