Inventory: 10 of the loneliest, bitterest Paul Schrader characters

As Richard Gere reunites with Schrader for Oh, Canada, we looked back at the filmmaker's most pitiable creations.

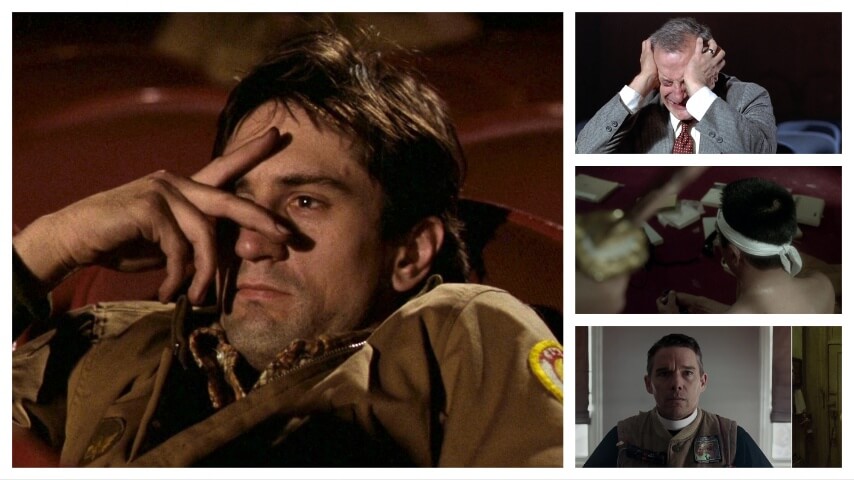

Photo: (clockwise from left) Columbia Pictures, Columbia Pictures, Warner Bros., A24

To truly be regarded as one of Hollywood’s leading men, you need to possess a dynamic range of performance skills. Sharp comic instincts, an unconventional sex appeal, and an ability to express rich, contradictory emotions have all proven to be tickets to celebrity and critical acclaim. But there is a more selective pool of actors who can do all of the above and evoke a bitter sense of isolating, existential grief that’s both pitiable and repellent—that is, they have all been a Paul Schrader character.

Robert De Niro, Ethan Hawke, Richard Gere, Oscar Isaac, Nicolas Cage, Nick Nolte, George C. Scott (if you need proof of Scott’s sex appeal, please watch Anatomy Of A Murder)—New Hollywood scribe Paul Schrader has inverted or weaponized the charm of them all, and they’ve gladly accepted the task of staring into the middle distance with intangible and often troubling visions of the world weighing down on them. Schrader has explained his screenwriting process as identifying a problem in his life then creating a metaphorical character, occupation, or situation that expresses that problem. The result is a tableau of people (usually men, usually white) locked into stasis or worse, deterioration by an unforgiving position in an uncharitable world, marred by loneliness and bitterness as a great change (often violent, often transcendent) looms ahead.

Decades after Richard Gere embodied the instability of the American freelancer in American Gigolo, the actor collaborates again with Schrader in Oh, Canada, where he plays Leonard Fife, a dying leftist filmmaker who recounts his life and confesses his mistakes to his own students on camera. You get the sense that Schrader sees his own relationship with fans, ailing loved ones, and an extended guilty conscience reflected in Fife—if not a direct mirror, then an opportunity to reflect on an artistic career closely positioned with New Hollywood, its commercial appropriation, and the long-term aftermath for independent film. At the center, though, is a man who is lonely, bitter, and sees the world differently because of it. As Oh, Canada arrives in theaters, we’ve curated a list of the loneliest and bitterest Paul Schrader characters.

1. Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver)

What’s Travis Bickle’s origin story? Where does he go after the events of Taxi Driver? One of the genius elements to Martin Scorsese and Schrader’s film is that the transitory stream of vignettes that make up Bickle’s life feel self-contained, like our gaze has been fixed onto him—making us stew in the curiosity, revulsion, and conflicted empathy of his miserable, hate-filled life. Travis cannot interact with the people around him in a healthy way, and the pushback he receives convinces him to cling tighter to a warped, vile perspective on the world that implicates his behavior in no way. Clearly, Travis is not well, but so much of his bitterness is self-inflicted; he’s so ashamed of mishandling his loneliness that the violent energy is turned on everyone else. Still, he roams the night in his cab, often silent and docile, every street corner or miscreant passenger a quiet affirmation of the world being sick according to his tastes.

2. Jake Van Dorn (Hardcore)

A prosperous single father, admired in his local religious community and free of any identifiable vices, Jake Van Dorn (George C. Scott) may seem like an odd selection in a list of demented avengers and self-loathing drifters. But as Jake ventures into the seedy Hades of Los Angeles porn to reclaim his property, the teenage daughter who absconded from his oppressively conservative household for West Coast sex work, his confidence in his worldview takes some serious, profane knocks. Perhaps no other ‘70s actor could have pulled off Van Dorn’s crusade of Calvinist hypocrisy—Scott’s bug-eyed growling and stern rhetoric affirms his “Army of One” status at every obstacle. But while Jake’s bitterness at a world gone to rot is never in doubt (conveniently, everything outside of his patriarchal home and small-town influence is apparently corrupt), Hardcore reveals the extent of his alienation throughout the film: his daughter Kristen’s confession of willingly entering the porn world to escape him, plus his final rejection of a young sex worker who he’s treated like a Kristen substitute the whole film, demonstrates how incapable of true compassion and empathy this man is. He returns to his old life, everything seemingly repaired, with the knowledge of his own miserable failings.

3. Julian Kay (American Gigolo)

Richard Gere’s first collaboration with Schrader (released 44 years ago) feels like the spirited, narcissistic mirror to Oh, Canada. Instead of being sick, elderly, and guilt-ridden, Gere is pure sex in a designer suit; instead of being a leftist filmmaker like Leonard Fife, Julian makes pleasure his art, serving the lonely, pining, and wealthy women of Los Angeles. American Gigolo compels through how we examine the layers of Julian’s life: he resents his obligations to pimps, he won’t suffer clients wasting his time, he depends on the trust of his rich benefactors. But his full-bodied commitment to an aloof, materialistic life makes him a professional target—making all your relationships transactional inadvertently gives your life a value, and when it’s convenient to implicate him in a violent crime, there’s little he can do to push back against it. Julian’s loneliness never really changes throughout the film, he only realizes how vulnerable it makes him when the structural protections he refused come back to bite him.

4. Yukio Mishima (Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters)

Many of Paul Schrader’s poorly-adjusted characters observe an unbalanced world and try to correct it with violence. While there’s no doubt the controversial, fascist Japanese author Yukio Mishima made attempts to enforce his will on his contemporary society, the greatest violence he wrought in his lifetime was self-inflicted. A queer, ardently right-wing man who detested how Japan’s kokutai (“national essence”) was being lost in the increasingly globalist period following WWII, Mishima’s prose fused art and death in what could be dubbed national fetishism. Throughout Schrader’s unconventional biopic (which recounts Mishima’s fatal failed coup, a black-and-white autobiography of his life, and colorful enactments of his novels), Mishima’s solitude is front and center, as he commits himself further to the notion that the artist must be physically and spiritually worthy of the pure art they wish to create. Schrader’s masterwork is a theatrical, expressionistic symphony that hones in on the sonorous but spiraling manner in which an artist sees a world of failure, and he is willing to destroy himself in order to redeem it.

5. Patty Hearst (Patty Hearst)

Patty Hearst (Natasha Richardson) isn’t just the only female character on this list, she’s the only one from a film that wasn’t scripted by Paul Schrader. Patty Hearst tells the story of the kidnapped heiress who started (under duress) collaborating with her kidnappers, the radical Symbionese Liberation Army, directed by Schrader but written by Nicholas Kazan—whose father Elia knows a bit about telling stories about left-wing radicals. Schrader’s film makes it clear there is nothing noble about the SLA or their treatment of Patty—a politically inarticulate and praxically ineffective group who isolated and conditioned their hostage to accept their will and identity as her own. Patty’s loneliness is apparent throughout, even as she chases the acceptance and affection of the radicals (she never escapes the lower hierarchical position that they allocate her), but it’s not until her arrest that the bitterness truly takes hold. Richardson’s timid, disoriented demeanor hardens into exhaustion and resentment as Patty levels with how much her agency was eroded by her comrades. In one of the strongest “prison visitation” finales of Schrader’s career, we leave Patty not in helpless despair, but with a resolute, hardened perspective on how she was ignobly used for no great purpose.

6. John LeTour (Light Sleeper)

“What am I doing with my life?” is so common a mid-life crisis mantra that its existential weight has been saturated throughout capitalist cultures. But Schrader was never one for softening the true crushing power of existential aimlessness. Willem Dafoe, a reliable Schrader supporting player, takes a rare lead role here (not counting the Schrader-scripted, Dafoe-starring The Last Temptation Of Christ). LeTour is a 40-year-old sober insomniac relegated to couriering high-class drugs for invulnerable financial sector clients, and his adriftness snaps into urgency after he bumps into an ex (Dana Delany) and confronts the go-between-like passivity of his life. Dafoe’s sad, heavy eyes evoke contemplative self-pity throughout Light Sleeper, which helps enhance the softer, melancholic tones in a crime narrative Schrader has returned to throughout his career. LeTour’s isolation feels less the designed consequence of a violent world, like in American Gigolo, but more like an evocation of a lost soul who fears he may never find his place.

7. Wade Whitehouse (Affliction)

Only two actors have won an Oscar for playing a Paul Schrader character, and while James Coburn’s performance as the senile, abusive father of New Hampshire policeman Wade Whitehouse (Nick Nolte) is not as iconic as Robert De Niro’s Raging Bull win, he’s an intimidating and powerful presence in a film about fragile, bullish men succumbing to the pull of violence—especially if they were once victims of it. Affliction is the first Schrader film to adapt Canadian author Russell Banks (Oh, Canada adapts his novel Foregone) and was released the same year as the best-known Banks adaptation, The Sweet Hereafter. Schrader and Banks feel like kindred artistic spirits, eager to understand a wealth of quietly destructive relationships and the moral conditions that challenge or corrode the human soul. Wade feels like the pinnacle of their bleak interests—an alcoholic deadbeat divorcee whose blinkered, bruised sense of justice and resentment of his father leads him to a place of complete mental isolation and ugly fatalism about how to repair (through violence) the wounds of his inner world.

8. Frank Pierce (Bringing Out The Dead)

Many Paul Schrader characters have a job or charge that conditions how they feel about the world, about its injustices, chronic illnesses, and self-destructive tendencies. Like the next character on the list, Frank Pierce’s job is deemed a noble one by society, but the punishing reality of being a Manhattan ambulance paramedic undermines any altruism of his profession. Permanent exhaustion and depression push Frank (Nicolas Cage) to the brink of his sanity, with the daughter (Patricia Arquette) of a cardiac arrest victim as his only lifeline. In their fourth collaboration, Schrader and Scorsese deepen their excavation of that bruised, throbbing meeting point between brutality and transcendence, showing a man whose inability to save the desperate, despondent souls of New York starts feeling like a personal fault, before it collapses into existential grief. In such an ugly and powerless system, when our first responders are numb to the vibrancy of human experience, how can any of us hope to be saved?

9. Rev. Ernst Toller (First Reformed)

Who is lonelier than the minister who has lost touch with God? Who can be more bitter than a man who blames his fellow men for God abandoning them? Reverend Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) certainly isn’t lacking in self-loathing and guilt—he is divorced, alcoholic, and dying, a former Army chaplain whose family fell apart after his son died in Iraq, for which he feels personally responsible. But it’s this wounded humility that fuels his holy mission—an act of violence to stop planet-destroying industrialists washing their bloody, oil-slicked hands with the faded white paint of his church. Schrader purposefully channels Ingmar Bergman’s thesis of human love marking the true presence of God, but Schrader takes us to more explicitly bilious, grisly places before Toller is allowed to see the light. Maybe Toller’s religious disposition is why Schrader spares his criminally-inclined protagonist the incarcerated fate that befalls nearly half the characters on this list—God may not be a way out of loneliness, but believing in Him can help you find others to cure your condition.

10. William Tell (The Card Counter)

In one of the most willfully provocative protagonist backstories of Schrader’s career, William Tell (Oscar Isaac) is a former soldier who spent eight years in a military prison for his role in torturing prisoners at Abu Ghraib. He taught himself card counting and now traipses around America’s dead-air casinos making a meager living for himself—until his suppressed, vengeful fury towards his commanding officer (who was spared a prison sentence) resurfaces. All we know about William is how suited he is to prisons—the prison he committed atrocities in, the prison he was sent to for following America’s orders, the prison of the casinos he frequents, playing blackjack to get by and retreating back to self-enforced solitude afterwards (another prison). Isaac’s emotionless eyes and flat-toned voice make Tell feel instantly like someone who is in a holding cell somewhere else, far away, waiting until they discover a meaningful, appropriate punishment for what he did. His resistance to inflicting the most easily cathartic and brutal punishment on his old superior only stokes the flames of his bitterness and indignance. The final, prison-set scene of The Card Counter is nothing we haven’t seen before, but because it’s happening to one of Schrader’s most nihilistic characters, it feels different: Tell has been trying to touch others through a pane of glass the whole film.