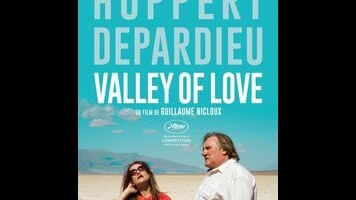

Isabelle Huppert and Gérard Depardieu reunite in Valley Of Love

Arriving in U.S. theaters nearly a year after it largely mystified audiences at Cannes, Valley Of Love stars Isabelle Huppert and Gérard Depardieu as famous French actors named Isabelle and Gérard, whose respective careers, when discussed, sound identical to Huppert’s and Depardieu’s own. Are they playing themselves, then? Not exactly, because Isabelle and Gérard were once married, whereas Huppert and Depardieu have only ever been colleagues. (They previously appeared together in Bertrand Blier’s Going Places and Maurice Pialat’s Loulou; this is their first onscreen pairing since 1980.) The film’s writer-director, Guillaume Nicloux, apparently has a taste for this sort of playful metafiction; his previous feature, The Kidnapping Of Michel Houellebecq, stars real-life novelist Houellebecq as himself, dramatizing false rumors regarding his alleged disappearance in 2011. In this case, however, it’s not very clear what’s gained from references to the stars’ celebrity, which seems irrelevant to the offbeat narrative surrounding them.

That narrative itself is both intriguing and intentionally frustrating. Valley Of Love takes place entirely in California’s Death Valley, to which Isabelle and Gérard have been summoned by their son, Michael (never seen). Six months earlier, Michael had committed suicide, but both parents have subsequently received a recent letter from him that refers to his death in the past tense. The letters also instruct them to follow an itinerary he’s laid out for them in Death Valley, consisting of seven specific locations at specific times, claiming that he will briefly reappear to them at one of the seven. Isabelle believes this wholeheartedly, while Gérard thinks it’s utter nonsense, and keeps insisting that he has to leave before the rendezvous in order to keep a crucial doctor’s appointment. Nonetheless, he’s shown up, a few days early, and the long-divorced couple spend some time hanging around their hotel and driving around the parched landscape, arguing and reminiscing and occasionally being (vaguely) recognized by starstruck tourists.

Such expert meandering, performed by two of France’s greatest actors, would be welcome if Nicloux had a stronger sense of what movie he wants to make. At times, Valley Of Love verges on Larry David-style cringe comedy, with Isabelle and Gérard harangued by ugly Americans who don’t know their movies but want to send them screenplays. One woman asks Gérard where he was born; when he replies “Châteauroux”—where Depardieu himself was born, inevitably—she asks if that’s near Greece. He politely nods. Meanwhile, a man repeatedly shouts obscenities at a nearby TV showing a football game. This material is often quite funny, but it clashes unproductively with Isabelle’s grief, and her bursts of anger at Gérard for not taking their son’s promise of temporary resurrection seriously. There’s almost a gender-reversed Mulder-Scully dynamic between the two leads, though Nicloux has zero interest in revealing what truth is out there amidst the majestic desolation. (The finale/denouement is a big ol’ tease.)

Nonetheless, it’s such a pleasure to be in Huppert and Depardieu’s joint company that the film’s failure to coalesce is to some degree forgivable, or just ignorable. Huppert, who’s nearly always terrific, gets the opportunity to play everything from comic exasperation to soul-shattering anguish, inhabiting each sudden shift in temperament with ease. Depardieu’s recent work has been a good deal spottier (United Passions, anyone?), but working opposite Huppert again seems to relax him, and he’s never been more at ease with his corpulence (for which Gérard bluntly apologizes when he and Isabelle reunite: “I got fat”). Valley Of Love is at its best when it wanders away from its ostensible premise and just lets two old pros connect, riffing lightly on our knowledge of their real-life histories. Adding a metaphysical mystery element to that rapport only serves as a distraction. It’s as if A Hard Day’s Night got crossed with Picnic At Hanging Rock.