Isabelle Huppert as Mrs. Hyde sounds like a much cooler movie than the one we get

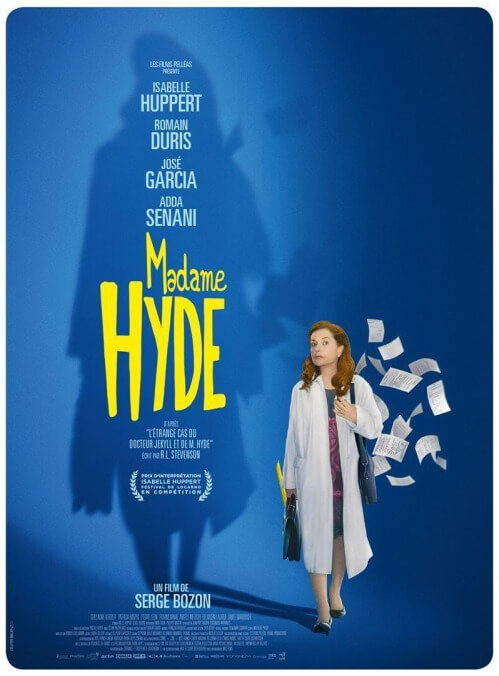

In theory, Mrs. Hyde serves as a kooky, gender-swapped French riff on Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, with Isabelle Huppert in the literally transformational role. Sounds appealing, non? Who wouldn’t want to see Huppert do the 19th-century equivalent of Hulking out, obeying her id’s darkest impulses? Unfortunately, Mrs. Hyde was written and directed by Serge Bozon, a filmmaker who seems perversely committed to frustrating not just conventional audience expectations but also any hope whatsoever that one might have for narrative and/or thematic coherence. Mrs. Hyde’s famous source material provides a basic foothold that was sorely absent in such previous, little-seen Bozon films as La France (a WWI musical) and Tip Top (also starring Huppert), which helps a little. But this is still a Jekyll and Hyde story in which the most dramatic, compelling scene involves a student who’s bad at math standing at the blackboard and laboriously solving a difficult geometry problem in real time.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.