It’s a bird... It’s a plane... It’s Superman, the first big-budget superhero movie

It’s become a common complaint among movie lovers: Superhero movies have taken over, and it’s hard to get anything made if it doesn’t feature people in capes. In its own way, it’s a valid point. The superhero movie has become the dominant form of American popcorn cinema, playing the same function that genres like Westerns and musicals played in decades past. In 2017, four of the top 10 worldwide highest grossers were superhero movies, and if anything, that number seems likely to grow in 2018.

But superhero movies are not the enemy. There have been great superhero movies over the decades, with directors like Tim Burton, Sam Raimi, Christopher Nolan, and Ang Lee leaving their stamps on the genre. These days, the people at Marvel seem incapable of cranking out a piece of entertainment that’s not, at the very least, a surface-level delight. And the left-field triumph of the superhero movie, a genre that seemed like a nerds-only fantasy vehicle a couple of decades ago, is one of the strangest things that’s ever happened to mainstream film.

This column aims to follow that history—to look at how superhero movies evolved into the juggernaut that they are today. As with my last column, the just-wrapped action-movie chronicle A History Of Violence, I’ll write about the most important superhero movie of every year since the modern version of the genre first came to prominence. That means I’ll be starting, in the next installment, with Burton’s 1989 movie Batman. But that’s not where superhero movies really started, and it’s not even the first modern big-budget extravaganza. It’s just the first place where I can realistically pick a movie per year.

This insanely comprehensive list names the first superhero movie as The Shadow Strikes. That movie came out in 1937, a year before Superman made his first appearance in Action Comics No. 1. But for more than four decades, the superhero movie was strictly relegated to B-movie status. Kids’ serials like The Phantom and Adventures Of Captain Marvel would screen before features. Every once in a while, a major character would appear in a campy feature like 1951’s Superman And The Mole Men, which was only an hour long, or 1966’s knowingly silly slapstick blast Batman, an extension of the Adam West TV series. It wasn’t until 1978 that someone finally saw the transformative potential of bringing comic book heroes to flesh-and-blood life.

Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie effectively birthed the superhero movie as we know it. It was the first one to pull in a big budget and big stars, to present its hero with some level of winking seriousness, and to employ state-of-the-art special effects. At $55 million, Superman was, at that point, the most expensive movie that had ever been made. Its production was famously troubled, with father-and-son producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind clashing bitterly and repeatedly with director Donner. The movie went way over budget and way over schedule, and the Salkinds eventually fired Donner from the movie’s sequel, which they were shooting at the same time. But it was still an overwhelming success, grossing a worldwide $300 million and launching a whole franchise. Even critics liked it. It did its job.

Watching Superman today, it’s striking to consider how much the movie has in common with the superhero movies that came decades later and also how different it is from its descendants. This might be the movie that birthed a genre, but it’s also a work of nostalgia. The movie opens with a black-and-white version of the Warner Bros. logo and a curtain opening. Before we see any actual humans, we see an old issue of Action Comics and fake newsreel footage of the Daily Planet. The audience, then, wasn’t just kids; it was also the adults who had grown up on Superman comics and who now got to experience the childlike thrill of seeing the man onscreen. That’s pretty much the audience for those movies now, too.

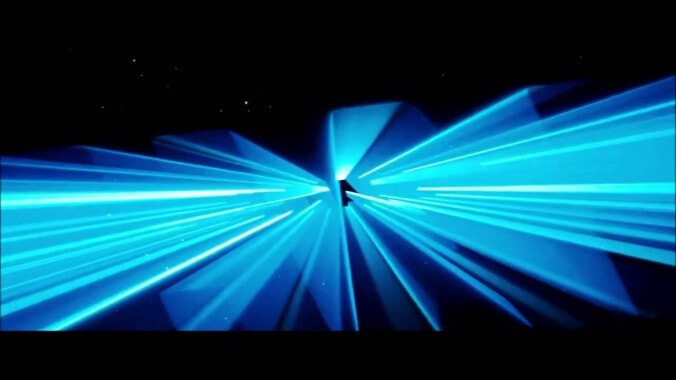

But when the fake curtain disappears and turns into color, we see something else: a vast expanse of space, with blue letters blasting across it and triumphal John Williams music playing. (To this day, I don’t think there’s been a better, more iconic score in a superhero movie.) That sight would have been familiar to audiences; Star Wars, which opened more or less the same way, had come out the previous year. Superman had begun shooting before Star Wars, but there’s at least a bit of swagger-jacking in that opening. And anyway, Star Wars had called back to the same old serials that had inspired Superman. It’s weird to think how much of the Hollywood blockbuster era came from ’70s directors attempting to recapture the low-budget thrills of their childhoods.

The real reason that the movie works—and it does work, for the most part, even when you rewatch it 40 years later—is Christopher Reeve, the then-unknown actor chosen to play Superman. I don’t know whether Reeve is an exact fit for the comic book version of Superman or whether my own personal image of Superman is just colored by this Reeve version being around for my entire life, but it’s hard to imagine any other actor embodying that strange mix of brawny handsomeness, charming sincerity, and physical comedy. As Clark Kent, Reeve is a gracefully screwball bumbler, and as Superman, he’s a warm and sheltering presence. The list of actors who almost got the Superman role is long and hilarious: Dustin Hoffman! Sylvester Stallone! Burt Reynolds! Paul Newman! (My favorite sentence from the movie’s Wikipedia page: “Both Neil Diamond and Arnold Schwarzenegger lobbied hard for the role, but were ignored.”) But after watching Reeve in the role, it’s hard to imagine anyone else playing it, even though the fact that the 6-foot-4 Reeve towers over everyone else in the cast makes it even more improbable that nobody would’ve figured out Kent and Superman were one and the same. The main problem that subsequent screen Supermans Brandon Routh and Henry Cavill have had is that they’re just not Christopher Reeve.

The movie, like so many of the superhero films of today, is bloated and overlong, and it devotes way too much of its energy to Superman’s origin story. The early scenes, set on Krypton, remain a total chore. Marlon Brando, playing Superman’s father, got top billing and a whole pile of money, and he sleepwalked his way through it as hard as he could, refusing to learn his lines and speaking them all with a vague distance that gives them an absolute minimum of urgency. (Also, he pronounces the word “Krypton” weirdly. Shit drives me nuts.) Brando ended up successfully suing the film’s producers for an even larger cut of the movie’s profits, which made his barely-there performance even worse. Brando’s involvement was a statement, and it’s pretty amazing how much A-list talent was involved in the movie, from Gene Hackman, still a straight-up movie star at that point, to The Godfather writer Mario Puzo, one of the movie’s four credited screenwriters.

The movie’s vision of Krypton, with its glowing disco jumpsuits and its planetary destruction depicted as crystals falling from the ceiling, is deeply boring. The stuff in Smallville, with a young Clark Kent learning to understand his powers and watching his father die, is a lot better. But it’s when Reeve finally appears in the knowingly ridiculous Superman costume, about 45 minutes into the movie, that it becomes something.

Like the superhero movies of today, Superman gets over on spectacle and banter. The spectacle is mostly miniatures shattering rather than CGI devastation; in its scale and aesthetic, it’s got a lot in common with the all-star disaster movies of the ’70s. But Donner—who got the job because he made a great larger-than-life pop spectacle with 1976’s The Omen, a very different movie—works wonders with crowd reactions, all those people on the ground freaking out at the sight of Superman. He also has fun showing all the classic Superman stuff, including the rescuing of an actual kitten from an actual tree. He’s got Gene Hackman, hamming things up delightfully, as Lex Luthor. (To date, Hackman’s the only halfway charismatic screen version of Luthor, even if it’s as broad and goofy as it gets.) And he’s got Margot Kidder as Lois Lane. When Reeve and Kidder are onscreen together, they look like two human adults with chemistry, something we rarely get in superhero movies anymore.

Plenty of the movie doesn’t hold together. Whenever things threaten to get too interesting, Brando’s ghost shows up to drone some more. There’s the flying-date sequence, where Lois Lane, in voice-over, starts dramatically reading the cheesy lyrics of a bad middle-of-the-road pop song that Donner cut from the soundtrack. There’s the climactic moment when Superman turns back time by making the planet spin backwards, which is not, as far as I know, how time or planets work. But overall, the movie worked as a charming spectacle. It’s more trapped in its era than Star Wars or Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, the other big sci-fi-ish blockbusters that came out around the same time. But it’s a type of grand-scale fun that hadn’t quite been captured in a movie before.

The movie ended up pulling in a ton of money—more than any other 1978 movie except for Grease, another nostalgic romp. (Now that I think about it, it’s not that hard to imagine late-’70s John Travolta as Superman.) And in retrospect, it’s a bit of a surprise that Superman didn’t lead to a much earlier superhero movie boom. It did, of course, spawn a franchise that did pretty well for itself. 1980’s Superman II, in which Superman does battle with rogue Kryptonians led by General Zod, may have aged better than the original, if only because the just-as-powerful bad guys give Superman’s fight some real stakes. 1983’s Superman III had a whole lot of slapstick comedy and a forced-in Richard Pryor, and it’s a total fucking mess, though the scenes in which Superman briefly turns into an asshole are a lot of fun. And 1987’s Superman IV: The Quest For Peace was produced by the schlockmeisters at Cannon Films, and it plays very much like a Cannon version of a Superman movie. Superman fights a vaguely Billy Idol-looking clone of himself made out of nuclear weapons, and Lex Luthor gets a bumbling rockabilly nephew played by Jon Cryer. I liked it a lot when I was a kid, but I was apparently the only one, and it served as a definitive end for the series.

While the Superman franchise went through its decline, there were other expensive superhero flicks that came out and flopped throughout the ’80s. 1984’s Supergirl was a Superman spinoff so hapless that it couldn’t even score a Reeve cameo; instead, it stranded great actors like Faye Dunaway, Peter O’Toole, and Mia Farrow in a cocaine-logic plot and a Xanadu-esque visual sensibility. Howard The Duck, meanwhile, was something even more baffling: a George Lucas-aided attempt to turn a surrealist cult favorite Marvel character into a ribald slapstick comedy for kids. The movie features duck boobs and a moment when Lea Thompson literally tries to fuck a duck. To watch it today is to feel profound, euphoric confusion. It ruined Stan Lee’s cinematic ambitions for his Marvel characters for an entire generation. And while the 1981 Disney comedy Condorman was just a blip on the cultural radar, it lost the company a pile of money and didn’t exactly improve its reputation as a maker of quality entertainment.

Some of those early superhero movies fared better, even if all of them play as deeply strange curios today. 1980’s giddily surreal space opera Flash Gordon pushed the camp elements of Superman way, way further, until the movie almost felt like one long running joke about itself. 1982’s Swamp Thing, the movie that Wes Craven made immediately before A Nightmare On Elm Street, uses a cult-beloved DC Comics character as the basis for a completely watchable soulful rubber-suit monster movie; the most striking thing about it now might be the presence of Ray Wise, still eight years away from playing Leland Palmer on Twin Peaks, as the scientist who would become the Swamp Thing. The Z-movie degenerates at Troma found their greatest-ever success with the superhero splatter-comedy The Toxic Avenger, launching their own extremely cheap franchise in the process.

So: After Superman, pretty much every attempt to translate comic book aesthetics onto the movie screen turned out to be some kind of failure, and there were certainly no successes on the level of the first two Superman movies. Maybe that’s why it took a decade for someone to crank out another superhero blockbuster.

Next time: With 1989’s Batman, Tim Burton defines the way a blockbuster superhero movie would work for generations to come.