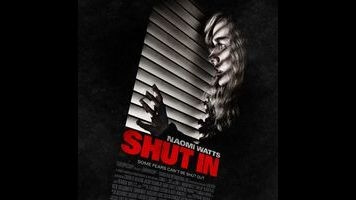

A thriller that takes a long time to get even remotely thrilling, Shut In spends much of its first half assembling elements that do, at least, inspire curiosity about just how they’ll combine to create havoc. A brief prologue sees clinical psychologist Mary Portman (Naomi Watts) bid farewell to her husband, who’s taking his emotionally troubled 18-year-old son, Stephen (Charlie Heaton), to some vaguely described special school. After a car accident leaves the husband dead and Stephen in a permanently catatonic state, Mary devotes herself to her stepson’s care, an exhausting ordeal. She also continues to see patients, and takes special interest in a deaf boy named Tom (Room’s Jacob Tremblay)—building up such a bond with him, in fact, that Tom suddenly shows up at her isolated Maine house one night, having run away from foster care (or something; this movie is not good on details). No sooner has Tom arrived, however, then he disappears, somehow inspiring what seems, based on news reports, to be a nationwide search. And there’s a major storm brewin’, which will clearly eventually deliver on the promise of the film’s title.

So that’s the (laboriously prolonged) setup: Isolated location, catatonic stepson, mysteriously missing deaf boy, big storm. Thing is, though, there’s no clear threat, apart from the storm. After Tom vanishes, Mary starts hearing strange noises reverberating around her big empty house, and repeatedly thinks that she sees Tom—at one point, the boy even apparently jump-scares his way beside her bed, clapping a hand over her mouth. (The movie then conveniently skips ahead to the next day, with Mary totally fine, ignoring the question of what happened next, or whether that had actually happened in the first place. Does she fall asleep a few seconds later? Does the Tom figure disappear? We never find out.) Mary regularly Skypes with a Dr. Wilson (Oliver Platt), who’s either her own psychologist or just a colleague—again, fuzzy on the details—and she tells him she thinks Tom may be a ghost. Dr. Wilson dismisses the idea as nonsense, and suggests that Mary may be suffering from a form of parasomnia, sleep disorders that can cause night terrors. A couple of definite dream sequences strengthen the latter hypothesis.

These and other red herrings, however, don’t really solve the movie’s basic problem: For ages, there’s nothing substantial for either Mary or the viewer to actively fear. Even if Tom is a ghost, he’s a decidedly unthreatening one, looking and behaving exactly like the timid little boy he’d been in life. After nearly an hour of Mary wandering nervously around and outside her dark house, clad in great-looking sweaters and being scared by raccoons instead of the usual cats, Shut In springs the twist that presumably landed Christina Hodson’s screenplay on Hollywood’s influential Black List, kicking the movie into gear at long last (though director Farren Blackburn’s notion of kicking things into gear involves more hiding in closets behind coats than one might prefer). Anyone familiar with Roger Ebert’s Law Of Economy Of Characters will have guessed the shocking surprise long beforehand, though some will mistakenly dismiss the possibility as too ludicrous to countenance. Watts gives her all to this overheated nonsense, but is powerless to make emotional sense of what turns out to be the story’s twisted central relationship, and ends up being just another fiercely maternal damsel in distress. By the end, Stephen’s catatonia seems enviable.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.