Move over, Rudy. Hit the showers, Brian’s Song. There’s a new tearjerking true story of gridiron triumph, one that combines those male-weepie favorites in a way no focus group could possibly resist. My All American, a football film as calculated as its title, runs through every cliché in the genre playbook. There are big games, bigger comebacks, roaring crowds, and not one, but two climactic, inspirational, halftime locker-room speeches. More crucially, perhaps, there’s also a tragic hero to enshrine, a departed legend of Texas athletics who the film treats with an awe and respect that borders on the Biblical.

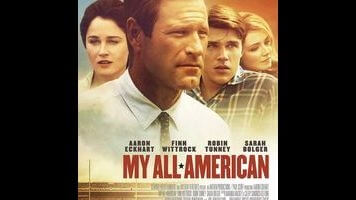

His name was Freddie Steinmark, and in the late 1960s, he overcame a relatively diminutive stature to become a star defensive safety for the University Of Texas Longhorns, before losing his leg and then his life to terminal bone cancer. Freddie was, by most accounts, an industrious go-getter, realizing his athletic ambitions through sheer gumption. But My All American—funded, partly and proudly, by several UT alums—sees more monument than man in his life story: Finn Wittrock plays Freddie as determination made flesh, a pure-hearted Christian boy without a single character flaw or unattractive quality. Men want to be him. Women want to be with him. Pigskin trembles at his approach.

Based on a bestselling biography on Steinmark, My All American was written and directed by one-man pep rally Angelo Pizzo, who penned both Rudy and Hoosiers. You have to admire, on some level, his commitment to the sport: This is a football movie that stops showing people playing football—in grandiose slow-motion, the crunch of a tackle always augmented by orchestral fanfare—only long enough for them to talk about football. When not setting the time and the place with blatantly expository dialogue (“Can you believe a man just walked on the moon?”), characters quote records and statistics at each other as though reading aloud from almanacs. This trend begins with the framing device, in which retired Longhorn coach Darrell Royal (Aaron Eckhart in bad old-man makeup) is regaled with a list of his own accomplishments by a college journalist, before he hijacks the interview to reminisce for two hours about his favorite player.

Back in ’60s Colorado, young Freddie, already on the fast track to glory, sets his eyes on Linda (Sarah Bolger), the new girl in class. Bolger gets one good scene, her character stammering nervously as the “coolest guy in school” asks her out, before becoming little more than an appendage on her beau’s legacy. “You’ve got nothing but football on the mind,” she accurately tells him, and indeed, Freddie has a habit of dragging her up to make-out point just to talk about his career goals. Though she ends up following him to UT instead of going to her dream school, the two don’t exhibit much chemistry. There’s much more (presumably accidental) tension between the star player and his burlier high-school teammate, Bobby (Rett Terrell), the Mr. Inside to his Mr. Outside.

Where’d Freddie get his drive, his hustle? My All American partially, uncritically traces it back to his demanding ex-athlete father (Michael Reilly Burke), often seen riding Freddie from the sidelines and—in one creepy rack-focus shot—obsessively spying on him from inside their suburban home. Otherwise, though, the film views its subject’s success as a product of strong, wholesome character: Unlike some of his countercultural peers, glimpsed during perfunctory remember-the-’60s protest scenes, Freddie doesn’t drink, smoke, or chase skirt, and he tellingly bonds with Coach Royal (Aaron Eckhart without bad old-age makeup) over their mutually short hair. Not quite a full-blown faith-based entertainment, My All American only tangentially nods to Freddie’s Christian beliefs, shoehorning a shot of him taking communion into a winning-streak montage and tilting the camera skyward during the four-hankie finale. There’s only so much reverence to go around, and the film saves most of it for the human hero it worships.

Maybe it’s that he just played a Norman Bates-like psycho on American Horror Story, or that he looks vaguely like a young Christoph Waltz, but there’s something unsettling about Wittrock’s approximation of gee-whiz ’60s youth. He’s oddly robotic in the role. Then again, it could just be that any traces of personality—of something other than heart and can-do conviction—have been scrubbed clean off the character. The real Freddie Steinmark, inevitably appearing in photographs before the roll of the end credits, surely had more dimension than a memorial statue brought to life. This Freddie exists only to love football and to be determined and to overcome adversity and then, finally, to stand proud and one-legged at the Cotton Bowl, in a scene the whole movie is just ghoulishly building toward. The man probably deserves a better film. We certainly do.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.