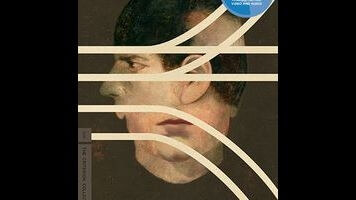

To strengthen that thesis, Kieslowski, who also wrote the screenplay, provides three iterations of the protagonist’s life, rather than the two that make up Sliding Doors. In the first, med-school dropout Witek (Boguslaw Linda), still reeling from the recent death of his father, just barely manages to catch the train to Warsaw. On it, he meets a Communist Party official (Tadeusz Lomnicki), and this chance encounter leads to Witek joining the Party himself, becoming a (relatively benign) tool of state oppression. The film then rewinds to show Witek miss the train, collide with a station guard, and get arrested for something akin to disorderly conduct; while doing community service, he meets members of the anti-Communist resistance, and now becomes a radical agitator. A third version also sees him miss the train, but without the collision or arrest, thereby allowing him to be greeted by a female classmate (Monika Gozdzik). As a result, Witek decides to return to medical school, becoming a doctor and taking care to stay out of politics altogether.

This is a clever idea, and it’s certainly pointed enough that it got Blind Chance buried for six long years. (Even on this Criterion release, one censored scene remains, described in text and heard but not shown, as the footage was apparently never recovered.) There’s a strong whiff of bullshit about it, though. Did Kieslowski genuinely believe that adult humans are soft clay, ready to take the shape of whatever worldview they happen upon? One could make a case for children, but Witek is well into his 20s when he races for that train. The notion that he’s equally likely to end up anywhere on the political spectrum, following the lead of whoever he first runs into at a crucial moment in his life, comes across as cutely facile. And Kieslowski makes it worse by ending the film with a mordant joke, as Witek’s fate turns out to be exactly the same no matter which path he takes. Ultimately, nothing he does matters at all.

In later years, Kieslowski would explore some of the same ideas in more fanciful contexts, with greater success. The Double Life Of Véronique and the Three Colors trilogy—both previously released by Criterion—forge metaphysical connections between strangers; this creates a sense of mystery and ambiguity that’s decidedly missing from Blind Chance, which remains tethered to Witek’s perspective throughout. (He’s always the same person; only his circumstances change.) That said, each individual narrative in Blind Chance is compelling enough on its own terms that the film is still well worth watching, even if one rejects its rather glib assertions about human nature. Linda makes Witek surprisingly credible in all three scenarios while retaining character continuity across them, and the details of Polish political turmoil, as seen from multiple conflicting angles, consistently fascinate. (Bear in mind that the country was undergoing a major crisis at the time, and that martial law would be declared shortly after Kieslowski finished production.) Blind Chance is thus an important historical artifact in a way that Sliding Doors, however charming, can simply never be. Not in this particular universe, anyway.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.