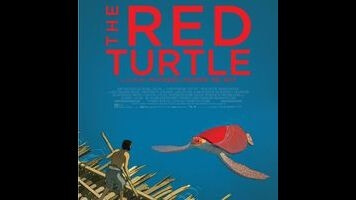

It’s man vs. allegorical reptile in Studio Ghibli’s stunning The Red Turtle

Part Robinson Crusoe, part All Is Lost, and part Heavy Metal, the animated feature The Red Turtle applies a distinctively European visual design to a primal tale of man against the elements. A collaboration between Oscar-winning Dutch-British animator Michael Dudok De Wit (who won for his 2000 short “Father And Daughter”) and the team at Japan’s Studio Ghibli, the film represents the medium at its most artful and entertaining. Though some may find its allusiveness and magical-realist turns to be overly fanciful, The Red Turtle nevertheless remains throughout a simple, gripping story of survival, deriving its sense of adventure from the most basic plot imaginable: Here’s a human being, stranded in a strange place, using his strength, intelligence, and courage to forge some kind of a life for himself.

Dudok De Wit (who also co-wrote the picture with Bird People writer-director Pascale Ferran) sets the tone right from the start, dropping the audience right into the middle of a roiling, stormy ocean with an unnamed sailor, who clings to a scrap of his ship until it carries him to the shore of a seemingly deserted isle. The Red Turtle is dialogue-free, aside from the hero’s occasional inarticulate shouts of frustration and rage, which are usually mixed so that they sound distant. Dudok De Wit’s compositions frequently emphasize how the vastness of the sea and sky dwarfs his protagonist. The framing serves both to magnify the ominous power of the surroundings and to make it so that the character’s inkblot eyes and shaggy mop of hair and beard are as much expressive facial detail as he needs.

Roughly the first third of The Red Turtle follows the castaway’s exploration of his new home, which is filled with haunting forests, edenic lagoons, and dangerous caves, all populated with enough critters to keep him fed. Then he builds a raft and tries to sail back to civilization, only to have his journey stopped before it begins by a giant red-shelled sea turtle, which destroys his makeshift vessel—and each subsequent one he constructs. Man and reptile stay locked for weeks in a strange standoff, until, about halfway through the film, the sailor awakens to discover that his reptilian foe has been transformed into a beautiful woman.

What happens next is a mix of metaphor and naturalism, presented in a style so spare that it has the feel of a half-remembered dream. Dudok De Wit favors the thin, “clean” lines common to many European comic book artists, like Jean “Moebius” Giraud and Georges “Hergé” Remi. With the help of Ghibli’s artists and technicians—supervised by Grave Of The Fireflies/The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya director Isao Takahata—The Red Turtle is both minimalist and vividly rendered, from the computer-animated waves to the well-articulated hand-drawn human figures.

The pure aesthetic beauty of The Red Turtle carries the movie a long way, compensating for moments when it ranges too far into the elliptical—or even the inexplicable. It also helps that no matter how surreal and allegorical that Dudok De Wit and Ferran get, they ultimately keep the story grounded in the immediate needs of their protagonist. Roughly every 10 minutes or so, something breathtaking happens, whether it be a daring escape through a tight underwater tunnel or a tidal wave that swamps the island, leaving devastation in its wake. Yet even amid the life or death moments, The Red Turtle finds time to appreciate the childlike joy of uncorking a bottle, or the gray-toned wonder of a moonlit beach. This film is a triumph of illustration, serving a story that’s intensely aware of both the big mysteries of human existence and the small ways that a crab scuttles across the sand.