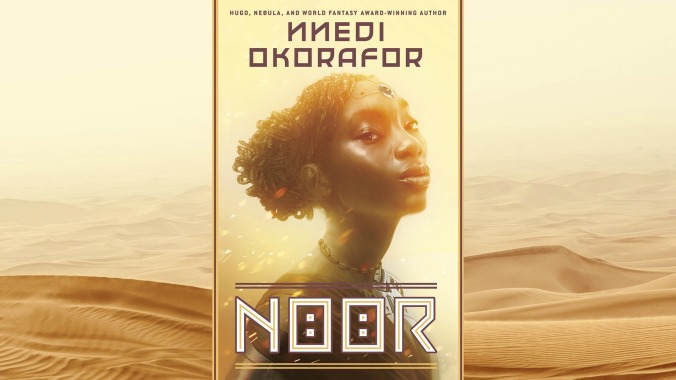

It’s nature vs. technology in Nnedi Okorafor’s fast-paced novel Noor

In her latest Africanfuturistic novel, Hugo Award winner Nnedi Okorafor tells the story of one woman who brings down the world order

Nnedi Okorafor has an uncanny ability for creating intriguing survival tales within grandiose Africanfuturist worlds. Author of Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winning works such as the Binti trilogy and Who Fears Death, Okorafor explores identity, war, and colonialism with a steady hand. Now, in Noor, Okorafor once again tells the story of a woman who by all accounts is considered a powerless outsider, yet ends up bringing down the world order.

The author immediately thrusts readers into the thick of the action, with the narrator staring down the swirling belly of the “Red Eye,” a continuous, deadly wind storm that looms in Noor’s Northern Nigeria. Okorafor then flashes back to 48 hours earlier, which is when we meet AO.

AO, born Anwuli Okwudili, changed her name to Artificial Organism when she was 20 years old. The late-twentysomething resides in the smaller city of Abuja, where she just separated from her fiancé. Born with weakened legs, one arm, and organ damage, she was patched up using advanced technology courtesy of the government. At the age of 14, she was involved in a rare autonomous-automobile crash, which further damaged her legs, resulting in AO pleading to receive state-of-the-art mechanical augmentations.

As a result, AO walks on tremendously strong legs that can lengthen as well as grip any surface. Her prosthetic arm allows her to work as a mechanic on pretty much anything, from the standard vehicle to cell phones. To treat the memory damage from the accident, she received neural implants, which so far only cause splitting headaches.

In this not-so-distant future, widespread discrimination persists against those with mechanical body parts and cybernetic organs. Those like AO are considered not only outsiders but “demons” and “Non-Africans,” and face brutal attacks throughout Nigeria. Which is why a regular trip to the market for AO becomes a bloodbath when a group of men try to attack her. Scared and well aware of the consequences awaiting her, she drives her car into the northern desert until it runs out of solar power.

There she meets another outcast on the run. Dangote Nuhu Adamu, or DNA, is a traditional and stoic Fulani herdsman with a devoted attachment to his steer. With his belief in folklore and heightened understanding of natural forces, DNA comes to represent the power of nature; AO, with all of her augmentations and knowledge about surveillance tech, the power of the interconnected web of technology. With DNA having been implicated in a recent terrorist attack, the two become enemies of the state and the corporation that keeps it all together, and they flee in a tense chase.

Okorafor excels in fast-paced narratives. As in Binti, she doesn’t get caught up in the nitty-gritty details, instead painting vivid images with broad strokes. Noor is around 200 pages long and moves briskly, yet still fleshes out the harrowing complexities of late-stage capitalism, colonialism, perceived disability, and climate change.

Okorafor explores the dichotomy of nature versus technology throughout Noor, giving an equal reverence for each as both maintain a significant presence within AO’s world. Solar energy is widespread, as are the wind turbines called Noors. The sun is honored and life-giving, but also a punisher and commodified by companies like Ultimate Corp (Okorafor’s clear stand-in for Amazon). The survival tech harnesses water and protects from the wind, but has its limits against nature’s prowess.

Even AO herself, nearly half machine and half human, represents this balance and the power that lies within both. AO views the fully connected world of technology as “pomegranate eyes,” imposing the unnatural on what is natural. The scale of life-giving technologies matches the richness offered by nature’s bounties like plantains, water, and marijuana. All of this anchors a compelling reflection on man’s principal role in climate disaster and the need to use technology to continue living in an altered world.

Every man she encounters asks AO, “What kind of woman are you?” The answer unfolds, bit by bit, over the course of the novel. Despite being half machine, AO asserts her womanhood, and refuses to be defined by others’ standards. She’s undeterred by her community and family’s thoughts on her augmentations and marvels at her own abilities, thinking of the searingly painful path she took to get where she is. Living outside of comfort for her entire life, AO becomes the one person unafraid of losing capitalism’s conveniences in order to create a new future, with a tenacity that lingers long after the novel’s final pages. As a result, Okorafor crafts an unconventional hero’s tale that calls into question what we’re willing to lose for a better future.

Author photo: Anyaugo Okorafor