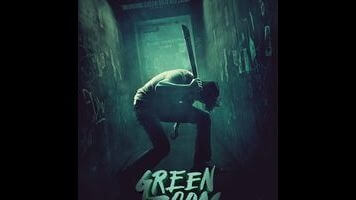

It’s punks versus Nazis in Green Room’s grisly, terrifying battle of the bands

Green Room is a rare gift from the genre gods: a nasty, punk-as-fuck midnight movie made by a genuine artist, a filmmaker with a great eye and a true understanding of the people and places he’s splattering in viscera. His name is Jeremy Saulnier, and his last film, the similarly color-coded Blue Ruin, was an eccentric riff on the revenge thriller, featuring a soft-spoken, sad-eyed vagrant in the Charles Bronson role. Green Room, about a traveling hardcore band caught in a life-and-death standoff with white supremacists, is even better, even bloodier, even more grimly amusing than its predecessor. In clichéd rock-journalism parlance, it’s a bastard lovechild, what you might get if you could somehow mate one of Kelly Reichardt’s portraits of life on the Oregon fringe with one of John Carpenter’s castle-siege action vehicles.

The title is the setting: the dingy backstage of a hole-in-the-wall music venue, somewhere in the outside radius of Portland and deep into the ugliest recesses of skinhead America. After an endless night of horrors, these four walls—muffling the nearby roar of electric guitar, adorned with swastikas and band logos alike—will end up looking more red than green. At first, though, the room is just an ordinary waiting area, where jokey singer Tiger (Callum Turner), nervous bassist Pat (Anton Yelchin), level-headed guitarist Sam (Alia Shawkat), and hotheaded drummer Reece (Joe Cole) prepare for a replacement gig, the final stop on an aborted tour. The Ain’t Rights, as these out-of-town punks call themselves, have no white-power affiliations, but they need the money to get home. So why not have their cake and get paid for it too by taunting the bare-skulled crowd with a cover of The Dead Kennedys’ “Nazi Punks Fuck Off”?

“A dumb idea,” one of these shit-stirrers puts it. He’s not wrong, but the real trouble (and the stomach turning and the screw tightening and the full-tilt carnage) arrives after the show, when The Ain’t Rights stumble upon a gruesome murder in the green room, and soon find the hulking, gun-toting doorman (Eric Edelstein) blocking their exit. “We’re not keeping you,” they’re told, calmly. “You’re just staying.” Green Room establishes its breathlessly intense, pressure-cooker scenario and then escalates it through a no-win negotiation: As the good guys slowly realize what the bad guys know from the start—namely, that as the only witnesses to the crime, they won’t just be allowed to walk away—the holding cell our heroes hope to escape becomes a fortress to barricade. And on the other side of the door, hick stormtroopers with buzz cuts, jack boots, and red laces get ready to prove their worth to the movement.

In the most menacingly effective stunt casting since Albert Brooks in Drive, Patrick Stewart plays the club’s paternalistic owner, rallying a posse of “true believers,” even as he feigns talk of peace with his captive guests. (The performance doesn’t so much rob Stewart of his signature regal civility as put it in a frightening new context, though you better believe Saulnier gets some shock value out of hearing Captain Picard say a racial epithet.) There’s something deeply, perhaps historically unsettling about the rational way these backwater neo-Nazis send their plot into motion, remembering to balance the books and selecting the weapons that leave behind the least evidence. But Green Room still resists making its villains faceless foes; they’re under duress, too, and plagued by crises of loyalty. A friend of the dead girl, Amber (Imogen Poots, all attitude) finds herself allied with the band out of mutual wrong-place wrong-time circumstance. There’s also Gabe, the runt of the heavy’s army, granted no respect for meticulously cleaning up messes; as portrayed by Blue Ruin star Macon Blair, he’s an unlikely creation—the sensible, put-upon Nazi. Hell, even the big oaf on guard duty is granted a sliver of empathy.

Pity, then, that empathy won’t save anyone in a film this pitiless. Characters don’t get killed in a Saulnier movie, they get annihilated. The violence in Green Room is swift and hideous, demonstrating the damage a bullet, a knife, a set of canine chompers, even a box-cutter can do to the human flesh. And when the actors respond to that violence, they do so not with gritted-teeth steeliness, but the full pain and panic one might expect from any ordinary person caught in this situation; a scene involving some exposed meat and a sharpened machete brings to mind Deliverance, specifically the way John Boorman let a femoral fracture shatter every macho bone in a young Burt Reynolds’ body.

There’s a dark, implicit joke here in people who only act fierce on stage being forced to really harness that aggression off of it. But Green Room isn’t savaging the scene; the film has a smart grasp on the hand-to-mouth lifestyle of road dogs, and a stronger sense of the lingo and sweatbox atmosphere of divey punk bars. Early scenes of The Ain’t Rights siphoning gas and crashing on couches are engaging enough—and crisply filmed, in hues true to the title—that if the bloodshed never arrived, the film might still look like a fine addition to the counterculture canon. Thankfully, Saulnier had more in mind. He’s drawn to the frazzled, the hapless, the mistake-prone, and if Green Room, like Blue Ruin before it, can’t ultimately resist the visceral thrill of vigilante justice, at least it isn’t afraid to make its characters look scared and weak and powerless and recognizably human. That focus on pure desperation—as opposed to cucumber-cool competence—gives hard-charging genre scenarios a serious shot in the arm. Or in this case, a few gnarly lacerations to it.