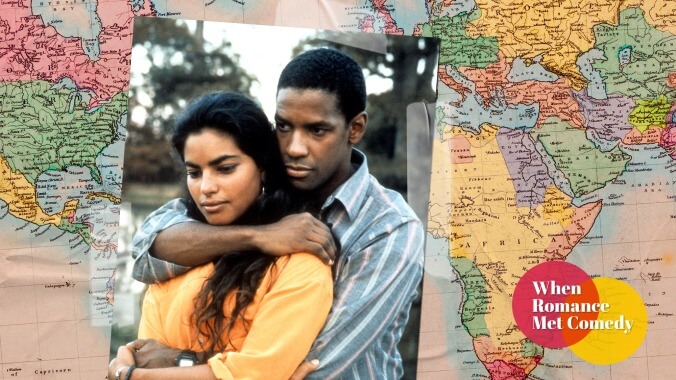

It’s time to rediscover one of Denzel Washington’s loveliest and most under-seen romances

Image: Photo: Samuel Goldwyn CompanyGraphic: Libby McGuire

In the age of streaming, it’s easy to assume that everything is just a click or two away. But even our biggest movie stars aren’t guaranteed to have their entire filmographies online. Two years after he won an Oscar for Glory, Denzel Washington starred in Mississippi Masala, a Romeo And Juliet-style romantic dramedy about a black carpet cleaner and an Indian motel employee who find love in Greenwood, Mississippi. Though it earned solid reviews, the 1992 film made a slim impression at the box office. And it’s yet to make its way to a digital streaming platform, not even as an iTunes or Amazon rental (although you can rent it through Netflix’s surprisingly still operational DVD mail program). It’s a shame because Mississippi Masala is exactly the kind of movie that deserves to be rediscovered today: a wholly original story written and directed by women that thoughtfully explores the complexities of interracial love between people of color.

Washington wasn’t the only Oscar honoree involved in Mississippi Masala. Director Mira Nair’s 1988 debut narrative feature, Salaam Bombay! had received an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. The Indian-born, Harvard-educated director came from a background in cinéma vérité and documentary filmmaking, which she utilized in Salaam Bombay! by casting real-life children from the slums of Mumbai to fictionalize their lives. For Mississippi Masala, Nair took loose inspiration from her own cultural experiences: “When I arrived [at Harvard] I was accessible to both white and black communities—a third-world sister to the black community and Kosher to the others—yet there were always these invisible lines. I felt that there was an interesting hierarchy where brown was between black and white.”

Nair re-teamed with Salaam Bombay! screenwriter Sooni Taraporevala for Mississippi Masala, and they combined two other Indian-immigrant experiences for the film’s premise, which involves both the unexpected fact that lots of motels in the American South are run by Indian-American families and the history of Indian immigration and exile in Uganda. As Mississippi Masala details, during the late 19th century, British colonizers used indentured servants from India to construct the Ugandan Railway system. Some of those laborers chose to stay in the country after their contracts were done, and eventually rose to positions of economic prosperity. In 1971, however, Idi Amin staged a military coup and ordered the exile of all Asians living in Uganda.

Mississippi Masala opens by capturing the terrifying brutality of that expulsion. Successful lawyer Jay (Roshan Seth), his wife Kinnu (Sharmila Tagore), and their young daughter Mina (Sahira Nair) must leave Uganda with only what they can carry. For Jay, who has always proudly considered himself Ugandan first, the hardest blow is hearing his lifelong best friend Okelo (Konga Mbandu) echo Amin’s propaganda: “Africa is for Africans. Black Africans.” A despondent Jay has no answers for his daughter as she asks where they’re going, how long they’ll be gone, and if they’re ever coming back.

After that tense 15-minute prologue, the film jumps to the present where Mina (now played by Sarita Choudhury) is a bright, beautiful 24-year-old who’s assimilated to American life in Mississippi. Her mother runs a small liquor store, while Mina and her father work in a family friend’s somewhat seedy motel. While Mina’s parents limit their social circle to Greenwood’s tight-knit Indian-American community, she’s equally comfortable at a local nightclub where most of the other patrons are black. It’s there that she bumps into Demetrius Williams (Washington), the handsome young man whose van she accidentally rear-ended earlier that day. The accident is easily forgiven as they get to dancing. Mina wants to dump her dud of a parent-approved date while Demetrius wants to make an ex-girlfriend jealous. Soon enough, however, a genuine spark develops between the pair as well.

Demetrius and Mina’s love story is the easy, breezy centerpiece of a movie with big, complex ideas on its mind. Mina is of Indian heritage, but since she was born in Africa and grew up in the U.K. and the U.S., she describes herself as “mix masala,” the Indian term for a blend of spices. (Demetrius briefly mistakes it for a religious denomination.) As Nair explained of her film, “There is this very cerebral concept [at its center]: What was it like to be an African, but of Indian skin who believed India to be a spiritual home without ever having been there and to be living in Mississippi? And what if this world collided with that of black American[s] who believed Africa to be their spiritual home, but had also never been there? It must collide through love, because we must sell tickets!”

A year after Mo’ Better Blues harnessed the power of Washington’s sexuality, Mississippi Masala captured the peak of his romantic charisma. Nair—who met her Indian-Ugandan husband while researching the film—was adamant that Washington capture the “stupor of love” she was feeling at the time. As Nair recalled to The Guardian, “I told him that he couldn’t be rational, he just had to go there and be weak-kneed. He was looking at me really suspect. So I said that the point is that if you’re allowing yourself to be totally vulnerable, no defenses, then the female audiences will just eat you up.” Though Nair’s friend Spike Lee had warned her that Washington would never take his shirt off on screen, Washington was actually the one who suggested he appear shirtless at one point. “I told him that he didn’t have to,” Nair explained. “But he said that it needed it, and by that time he was in a stupor of love, in love with the movie.”

In her first acting role, Choudhury channels her newcomer awkwardness into the feeling of her performance, as Roger Ebert astutely observed in his review. Demetrius and Mina’s love story is a perfect blend of sweet and sexy. They’re both smart, practical young people who aren’t swept up in the notion of true love, but aren’t totally immune to it either. Nair and cinematographer Edward Lachman capture the sensuality of the couple’s connection without leaning into exploitation or exoticism. When Demetrius and Mina consummate their relationship during a trip to Biloxi, the camera lovingly highlights their warm skin tones against the white bedsheets.

It’s still rare to see a big screen interracial love story in America that doesn’t involve a white person. And nearly three decades after its release, Mississippi Masala remains one of the few onscreen depictions of an African American/Indian American romance. Demetrius and Mina’s relationship upends the tentative balance that exists among the white, black, and Indian communities in Greenwood. Earlier in the film, an Indian character attempts to prevent Demetrius from suing over the car accident by appealing to racial solidarity: “Black, brown, yellow, Mexican, Puerto Rican: all the same. As long as you’re not white, it means you are colored… All us people of color must stick together.”

But once Demetrius and Mina are discovered in bed together, that solidarity immediately disappears. The Indian motel owners withdraw their business from Demetrius’ carpet cleaning company, while a white woman who earlier bragged about helping Demetrius get a loan from the bank calls to revoke her support after hearing the gossip. The Indian community thinks Mina is dating beneath her, while the black community accuses Demetrius of trying to rise above his station (although not as much as if he were dating a white woman). Nair carefully peppers in dissenting voices as well, to reflect the fact that neither community has a monolithic point of view. But the sense of an unspoken racial hierarchy is palpable. Demetrius’ friend callously warns him, “You better leave them fucking foreigners alone. They ain’t nothing but trouble.”

Though the film explores Demetrius’ world (filled out with some great supporting turns from Charles S. Dutton, Joe Seneca, and Tico Wells), Mississippi Masala is first and foremost interested in the foibles and hypocrisies of Greenwood’s Indian community. They’re victims of racism, but they also perpetuate it, too, even just through colorism in their own community. (One woman gossips of Mina at a wedding, “You can be dark and have money, or you can be fair and have no money.”) While Mina’s father Jay was a progressive defense lawyer in Uganda, his worldview has hardened since his exile. Seeing his daughter with Demetrius stirs up old wounds, eventually forcing him to confront the full truth of his long-held grievances.

Nair was adamant that the film shoot on location, both in Greenwood and in Kampala, and flashbacks to the lush Ugandan countryside make Jay’s longing for his homeland all the more poignant. He’s spent years obsessively petitioning the new Ugandan regime to get back the property he lost in exile. Yet when Jay finally makes the trip back to Kampala, it’s not as cathartic as he expected. Nair isn’t interested in telling a simplistic story in which love easily conquers all. So while there’s hope in Demetrius and Mina’s boundary-breaking relationship, there’s a melancholy ambiguity to Mississippi Masala too.

Mississippi Masala offers a lot to dig into—occasionally too much, in fact. As Ebert put it, “There are really three movies here: the exile from Uganda, the love story, the lives of Indians in the Deep South, and really only screen time enough for one of them.” Yet that also means the movie can sustain all sorts of different interpretations. Mayukh Sen of Fader finds optimism in the message Mississippi Masala imparts, while University Of Tennessee professor Urmila Seshagiri published a fascinating paper on the “limits of hybridity” in Nair’s depiction of cross-cultural romance. As Seshagiri sees it, the happy ending of Mississippi Masala can only take place in a kind of liminal space outside of the world the film has established.

More than anything, Mississippi Masala makes you realize just how rare it is to see a truly original love story on screen, whether in the romantic comedy or romantic drama genres. It’s a film about everyday people that acknowledges that the lives of those people can be unique. And it’s a shame the film’s not more readily available now, especially given that the mainstream appetite for this kind of story has only grown since the early 1990s.

Thankfully, Nair has a wealth of other films that are easier to find, including her breakthrough 2001 Hindi ensemble drama Monsoon Wedding and her 2006 family drama The Namesake, which stars the late Irrfan Khan. In 2016, Nair returned to her interest in Uganda (where she lives part time) for the fantastic family film Queen Of Katwe, which tells the true-life story of a young chess prodigy from the Kampala slums. And while Mississippi Masala remains something of a hidden gem in the romance genre, it’s a reminder of the diversity of stories waiting to be unearthed by filmmakers willing to look for them.

Next time: Sooner or later, Something’s Gotta Give.