Dear studios: stop making 3D movies!

Unless it's an Avatar film, the 3D experience is an expensive, uncomfortable, and unsatisfying burden on moviegoing that may continue with Pixar's Elemental

Few moviegoing experiences are as discouraging as finding the perfect showtime for one of the year’s most-anticipated movies, only to discover it’s playing in 3D. As someone who spent a decade working at a movie theater, I’ve heard first-hand the gripes from customers about 3D offerings. From murky screens, blurry action, and wallet-draining upcharges on tickets, there are a lot of reasons for customers to lament the 3D experience. Yet, studios keep pushing it, ignoring all evidence of sparsely populated large format 3D screens for almost every film not directed by James Cameron.

And audiences have pulled back the curtain and seen the difference, revealing 3D to be less of an act of wizardry and more of a short con. The latest 3D release is Disney and Pixar’s Elemental, which was filmed in digital 3D, like most of Disney’s animated features. The probable thought process for Disney is the 3D element will draw audiences back to theaters after they’ve become used to watching Pixar movies at home on their televisions thanks to the studio’s Disney+ release strategy.

There’s also the fact the film is tracking for a modest $31–$41 million opening, so Disney is probably banking on 3D as an incentive for people to experience Elemental in the theater, rather than waiting 90 days until it hits Disney+. This bet isn’t much different from what prompted 3D movies in the mid-20th century, only then it was a novelty rather than the norm.

An ophthalmologist helps start a moviegoing craze

By 1950, movie theater attendance had fallen drastically as more American homes had access to television. Milton Gunzburg, a screenwriter for MGM, who believed the method through which he’d shot 3D home movies could be modified for the motion picture industry. Gunzburg, along with his brother Julian, an ophthalmologist, and cinematographer Friend Baker (who had been in the motion picture industry since 1915) developed a process for filming and projecting 3D features by way of dual-strip Polaroid filters. The only problem with Gunzburg’s solution was none of the studios were interested. 20th Century Fox, Paramount, and Gunzburg’s former home, MGM, all passed on the new technology. Ultimately it was former radio man and independent film producer Arch Oboler who saw the vision in 3D.

“A LION in your lap! A LOVER in your arms!” That was the promise attached to Oboler’s Bwana Devil (1952), the first English, feature-length, and colorized 3D film. Bwana Devil follows three big game hunters tracking down a pair of bloodthirsty lions attacking villagers during the construction of the Uganda Railway. The film was a hit with audiences and afterwards, the very same studios who’d passed on Gunzburg’s innovations were suddenly in the 3D business.

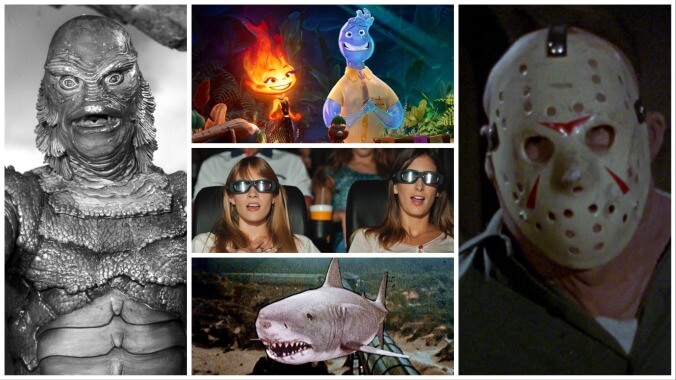

The following year, Columbia released Man In The Dark, Warner Bros. released House Of Wax (which Gunzburg was the 3D supervisor on), Disney joined the fun with Melody, and Universal-International came out with It Came From Outer Space. The rush to get 3D films to the screens resulted in many being projected incorrectly, out of sync, or damaged, which almost killed the 3D craze right as it took off. Yet, thanks to interest from filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock and Jack Arnold, 3D managed to survive a little longer, with Hitch’s Dial M For Murder (1954), and Arnold’s Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954) being the standout examples.

It wouldn’t be until StereoVision, a single-strip format developed by Allan Silliphant and optical designer Chris Condon in 1970 that 3D became technologically viable again. Still, it was a format used for pornos and horror movies, a means for small studios to rake in a lot of cash on cheap productions. Friday The 13th Part 3 (1982), Jaws 3-D (1983), and Amityville 3-D (1983) were popular releases during this brief revival, alongside re-releases of older horror films. For the next couple of decades, 3D was mostly reserved for theme park attractions.