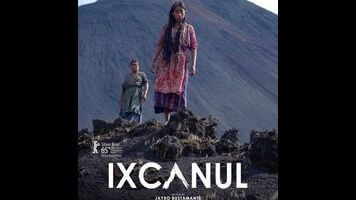

Ixcanul is a debut more explosive than the volcano it’s named for

When a Hollywood movie is called Volcano, the volcano in question is damn well going to erupt and threaten some B-list actors. There are no special effects to speak of, on the other hand, in the Guatemalan import Ixcanul, named after the word for “volcano” in Kaqchikel (one of the numerous Mayan languages spoken in Central America). The volcano itself, seen looming in the background of shots, functions primarily as a symbolic barrier; one character, asked what lies beyond it, replies “the United States,” parenthetically acknowledging Mexico as if it were a small vacant lot to be crossed en route. And while disaster befalls the film’s protagonist, it’s one that’s (almost) entirely of her own making—though it’s hard to blame her for wholeheartedly accepting the folk wisdom passed along by her well-meaning parents, even after said parents have told her, quite bluntly, that she shouldn’t necessarily believe every fool thing they tell her. This is a decidedly small-scale tragedy, but it still packs a cumulative wallop.

When she’s first seen, María (María Mercedes Coroy), who’s roughly 17 or 18 years old, is being prepped by her mother, Juana (María Telón), for an engagement party. Her father, Manuel (Manuel Antún), works for the local coffee plantation, and the family plans to marry María off to the plantation foreman, Ignacio (Justo Lorenzo), thereby ensuring that they’ll remain in Ignacio’s good graces. María, however, only has eyes for the comparatively impoverished Pepe (Marvin Coroy), with whom she hopes to flee to America. Pepe winds up leaving without her, but not before he gets her pregnant—a near-certain deal-breaker for Ignacio, they reasonably conclude. When efforts at abortion (including some comical hopping up and down near the volcano) fail, the family starts packing up to leave before Ignacio returns from a lengthy trip to the city and sees the enormous belly on his prospective bride. If they can just seed their field, though, maybe they can stay… and María has been told that pregnant women can frighten away the poisonous snakes that have previously made it impossible for them to use their plot of land as a bargaining chip.

It’s not really spoiling anything to reveal that a frantic trip to the hospital ensues. And that’s the point at which Ixcanul shifts from being a mildly interesting portrait of a little-seen community (at least in movies that make it to U.S. arthouses) to being a stealthily disturbing examination of the ways that indigenous people who remain in relative isolation get exploited by the handful of indigenous people who assimilate with the nearest urban center. What happens to María and her unborn child hinges heavily on the fact that she and her parents speak only Kaqchikel and must rely on Ignacio (who’s returned, and is indeed unhappy) to translate with the hospital personnel, who speak only Spanish. First-time writer-director Jayro Bustamante accompanies this abrupt shift from the country to the city with an equally abrupt formal shift, going jagged and handheld after nearly an hour of expertly composed shots in dreamy soft focus. Telón’s performance as María’s mother turns ferocious (in part because Juana blames herself for disseminating cultural nonsense), and the film, which had seemed simplistic for a long time, reveals itself as patiently corrosive. All in all, this is an impressive debut, the complete absence of lava and ash clouds notwithstanding.