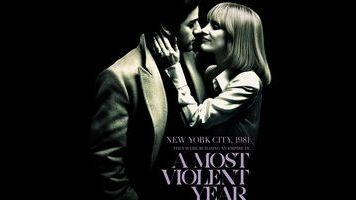

J.C. Chandor takes another left turn with the gritty A Most Violent Year

When Steven Soderbergh retired from feature filmmaking last year, American cinema lost its foremost chameleon—the kind of director who’s not interested in endlessly refining a particular type of film, preferring to explore every genre imaginable. It now seems that we may have his heir apparent: J.C. Chandor, who, over the past four years, has made three movies with virtually nothing in common except for the evident skill involved behind the camera. Margin Call, his dialogue-driven portrait of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, was followed in short order by All Is Lost, a survival-at-sea saga starring just one actor, Robert Redford, who says scarcely a word for the entire picture. And now here’s his third film, A Most Violent Year, set in 1981 and modeled on the gritty tales of New York City corruption that Sidney Lumet was making around that time. The effort at versatility alone would be impressive. More remarkable still, all three have been legitimately good, even if A Most Violent Year demonstrates again that Chandor has a tendency to be a tad overexplicit, thematically speaking, when his characters open their mouths.

There’s certainly an abundance of clarity in the film’s opening scene, which sees heating-oil magnate Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac), represented by his attorney (Albert Brooks, almost unrecognizable with straight hair), negotiate the purchase of an abandoned waterfront fuel yard. The terms are unforgiving: Abel has 30 days to fork over $1.5 million (closer to $4 million today), or he forfeits a sizable cash advance and the property gets sold to one of his competitors. Will things go wrong? Of course they will. Somebody keeps hijacking Abel’s trucks at gunpoint, and the district attorney (David Oyelowo) reveals that he’s conducting an investigation of the entire industry, with a special emphasis on Abel’s firm. Before long, the bank that had promised Abel the money for the deal pulls out, forcing him to beg wealthier rivals for loans, at terms highly unfavorable to him. Meanwhile, his trucks are still being robbed, and his drivers, now illegally carrying firearms at the insistence of the union boss, are engaging in shootouts on crowded highways. In order for him to meet his deadline, the personal integrity he so values will have to go on the back burner.

Chandor brings this intrigue to a marvelously slow boil, turning up the heat on Abel a degree at a time until his principles are in a puddle at his feet. There are a couple of exciting set pieces, including a superb chase sequence in which Abel pursues one of the hijackers along some train tracks, but A Most Violent Year is primarily interested in detailing the ways in which moral gray areas inevitably shade into true darkness. (The film’s penultimate scene features the coldest, most brutal silent decision since Breaking Bad’s Walter White chose to do nothing at the end of the season two episode “Phoenix.”) Its one problematic aspect involves Abel’s wife, Anna (Jessica Chastain), who’s instrumental in the fight to keep the business afloat. Thankfully, Anna isn’t the stereotypical movie wife who does nothing but whine about the protagonist’s reckless behavior, which is progress of a sort. But she’s basically that woman’s evil twin. Her sole function is to be even more ruthless than Abel, to the point where she even calls him a pussy at one point. She’s still not a full-fledged, complex human being with as much agency as the man; having her shoot a dying deer when Abel hesitates isn’t the same thing as giving her depth. Can Chandor make a first-rate film that isn’t a testosterone fest? That’s the next challenge—one that he shares with the industry as a whole.