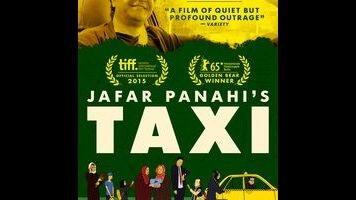

Jafar Panahi crashes the gates of censorship in a Taxi

Every new movie by Jafar Panahi is a miniature coup, an act of fearless political defiance. Banned from filmmaking by the Iranian authorities, who have kept him under house arrest for the last five years, Panahi risks his freedom, maybe even his life, each time he picks up a camera—which is surprisingly often for a man who’s been forbidden by law to do so. But can he really creatively thrive under lock, key, and watchful eye? This Is Not A Film and Closed Curtain, the first two films of the director’s house-imprisonment period, are more triumphs of personal expression than of filmmaking; testing but not transcending his restrictions, Panahi mostly succeeds in communicating the injustice of his situation. “This is what I can do under these conditions,” he seems to be saying, and the gap separating these one-location metafilms from earlier masterpieces like Offside and Crimson Gold becomes the whole point.

What’s special about Taxi, the third clandestine production Panahi’s managed to shoot and then smuggle out of Iran, is that it’s more than just an affirmation of its maker’s un-crushable artistic ambition. It’s also a nimble, funny, honest-to-God movie. Panahi again stars as himself, sometimes commenting on his own predicament and blurring the line between fiction and documentary. But it’s clear from the opening shot, a static glimpse through a car windshield, that this will be a new direction: By venturing outside the boundaries of his own home/prison, Panahi is both achieving a new level of disobedience and widening his focus to the outside world, to the ordinary citizens that have been all but absent from his work since he was arrested under charges of anti-government propaganda.

Unfolding in simulated real time, Taxi is mostly just Panahi, in very thin disguise, driving around Tehran in a yellow cab, picking up a cross section of Iranian society: two complete strangers arguing about the morality of capital punishment; a squat bootlegger, Mr. Omid, who regularly supplies the director with new works from international auteurs; elderly women racing across town to perform a time-sensitive religious ritual. Shooting almost exclusively from a “hidden” camera on the dashboard, Cash Cab-style, the director-star tips his beret constantly to the staged nature of these encounters, while still managing to make each socially pointed conversation feel lively and organic. It’s a strategy that fellow Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami would surely appreciate, though Panahi has a softer touch than his old friend and creative collaborator, whose own taxi-cab experiment, Ten, went considerably lighter on the yuks.

Getting behind the wheel of a car liberates Panahi. The space may be smaller, more cell-like even, than the house where he filmed his last two features, but it offers more mobility, more locations, more access to talent. The self-pity that permeated Closed Curtain has disappeared almost entirely, replaced by gently subversive humor. Even when Taxi goes didactic, it does so with grace; critiques of the Ministry Of Culture And Islamic Guidance, and its severe censorship restrictions, are filtered through the naïve chatter of the director’s adorably precocious niece, a young filmmaker determined to make a “distributable” movie. What emerges, through this series of half-comic episodes, is a portrait of a restless modern Iran, where artists and working-class citizens alike circumvent outdated laws to get what they need.

It’s Panahi, the personality as opposed to the filmmaker, who anchors the project. Visibly relieved to be out on the streets again, he plays himself as an amused observer, terrible cabbie (a running joke finds him berated by his passengers for having no idea where he’s going), and a kind of supportive uncle to young artists, as when he tells a film student fishing for a recommendation that “all movies are worth watching.” How the director is able to continually violate the sanctions against him, breaking not just his house arrest but also most of the Ministry’s guidelines, is a question that hangs heavily over the movie. Has Panahi become such an internationally visible and revered figure that his government now fears the consequences of further suppression? (The film won the Golden Bear at Berlin this year, which puts Iran in a tricky PR situation.) Or does the fact that there are no opening or closing credits here, with even the actors participating anonymously, indicate that he’s still very much playing with fire? Either way, Panahi shows no signs of quitting anytime soon, regardless of what the law says. If Taxi is what he can do under penalty, imagine what he’d accomplish as a free man again.