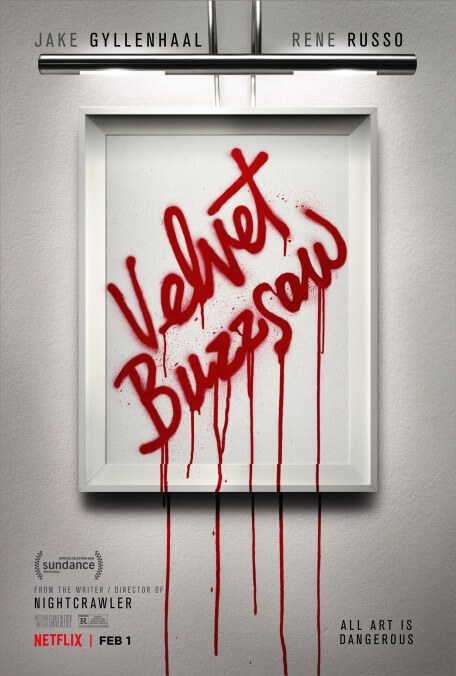

Jake Gyllenhaal reunites with his Nightcrawler director for toothless horror satire Velvet Buzzsaw

Watch a random few minutes from any of his movies and it becomes obvious that Dan Gilroy loves the cinema of the 1970s. It’s an obsession baked into the rhythm and downbeat trajectory of his work. Increasingly, though, one has to wonder: Have all of his insights been yanked from 40 years ago, too? Nightcrawler, Gilroy’s directorial debut, worked so well as a character study of a deranged go-getter that it was easy to forgive that its outrage over it-bleeds-it-leads journalism was about as timely as, well, the 1976 newsroom drama Network. There was nothing revelatory, either, about his baggy sophomore feature, Roman J. Israel, Esq., which dared to suggest that (gasp!) lawyers sometimes lose their sense of right and wrong when big cash is on the table. Now comes the concluding chapter of Gilroy’s Los Angeles no-duh trilogy, Velvet Buzzsaw, a facile slasher-satire with some very shopworn thoughts on the greed and superficiality of the modern art world. What’s next, a daring exposé of how politicians only care about money?

If he’s going to keep offering not-so-fresh takes, Gilroy could at least come up with characters as good as Lou Bloom, the nocturnal ambulance-chasing videographer that Jake Gyllenhaal brought to bug-eyed, maniacal life in Nightcrawler. But just about everyone in Velvet Buzzsaw is a caricature or straw men, a paradigm of messed-up priorities. That includes Gyllenhaal’s new character, Morf Vanderwalt, a withering, highly influential art critic, making and breaking careers in LA. “In our world, you’re God,” says Rhodora Haze (fellow Nightcrawler star Rene Russo), a former punk-rock frontwoman who now runs her own gallery. As the film’s baroquely animated credits sequence winds down, cinematographer Robert Elswit glides his camera through the swanky space, where a new opening becomes an opportunity to meet Gilroy’s collection of movers, shakers, and fork-tongued elites, including a museum curator (Toni Colette), a rival gallery owner (Tom Sturridge), a rising new talent (Daveed Diggs), and a falling star (John Malkovich).

Among these backstabbing power players, Rhodora’s assistant, Josephina (Zawe Ashton), is losing ground; though she’s shacked up with Morf, she’s lost favor with her famously fickle, demanding boss. That is, until an unexpected discovery: an abandoned stockpile of paintings, left behind in the apartment of her newly deceased neighbor. The dead man, an unknown artist named Vitril Dease, had no friends or family. So Josephina makes off with his work—a whole trove of tortured tableaus, plainly and strikingly communicating some inner demons—and parlays them into instant celebrity. Thing is, there’s something more than haunting about the paintings, which begin to make a rather literal killing in the LA art scene. As in, they begin to supernaturally murder those in Josephina’s orbit: hands creeping out of the canvas, adjacent artworks dangerously “malfunctioning,” revenge visited upon anyone profiting off them.

That makes Velvet Buzzsaw another of Gilroy’s studies of the way money corrupts institutions. There are moments, here and there, when the film taps into something queasy about the inner workings of this environment—the way, for example, that art buyers and advisers jockey for space in galleries and museums on the behalf of their moneyed clients, sometimes squeezing emerging talent out. But Velvet Buzzsaw, in its arch approximation of a Robert Altman mosaic, is more interested in the pretty squabbling and entwined personal lives of his characters—a direction that might prove more fruitful if these snobs, schemers, and faux- aficionados weren’t as two-dimensional as the paintings they scramble to monetize. As usual, Gilroy, brother of Hollywood heavyweight Tony, secures an A-list ensemble. But he forces this one to spew only diluted venom.

It’s tempting to wonder if the writer-director hasn’t made a veiled allegory about his own industry, which is just as ruled by competing interests and creatively bankrupt big spenders. Is Gyllenhaal’s petty intellectual tyrant a kind of revenge on the critics that didn’t shower Roman J. Israel, Esq. with praise? Truthfully, for as much as the film pokes fun at his breathless superlatives and constant kill-joy appraisals (“What is with this cheesy organ music?” he hilariously asks at a funeral), Morf counts as one of the the more charitable characterizations. Velvet Buzzsaw, in other words, spreads contempt in all directions. That’s not necessarily a problem—The Square, set against a very similar milieu, was plenty mean, but got some exquisite cringe comedy out of high-society foibles. Here, the jokes are mostly easy layups, like one character confusing a bag of trash in a mostly empty workspace for a brilliant new exhibit.

Would it have been too gauche to actually make the murders scary? Besides one grisly mishap involving a giant, reflective sphere with holes for guests’ hands, Gilroy’s big set-pieces are neither particularly inventive nor executed with much suspense-ratcheting brio. (What one wouldn’t give for the virtuosic showmanship of a Brian De Palma movie—or, hell, a lesser Final Destination sequel.) “All art is dangerous,” Rhodora sneers at a crucial moment, presumably summarizing Gilroy’s point. But if there’s undeniable difficulty in Velvet Buzzsaw’s genre alchemy—its attempt to mix a caustic, half-comic portrait of the gallery set with a supernatural Tales From The Crypt scenario—it’s all in service of a moldy screed about the commodification of art. Is there anything safer than telling people something they’ve heard a thousand times before?